An outspoken civil rights activist, Hazel Scott used her star power to fight racism. But then, she was accused of being a Communist — and it nearly destroyed her career.

Hazel Scott was once the most famous jazz virtuoso in the world, renowned as much for her talent on the piano as she was standing up against racism — until she was blacklisted for being a Communist.

Scott’s story in the spotlight began in 1928, when Dr. Frank Damrosch, the dean of Juilliard School, heard her playing in the audition room. He was shocked to discover that the classical protégé he heard was an eight-year-old girl with bows in her hair, her legs dangling off the piano bench.

At the end of her astonishing audition, Hazel Scott became the youngest person ever enrolled at Juilliard.

From there, her career skyrocketed, but her immense fame would also prove to be her undoing.

Hazel Scott, An 8-Year-Old Piano Prodigy

FacebookA three or four-year-old Hazel Scott.

Hazel Scott was born on June 11, 1920, in Trinidad and emigrated with her family to New York at the age of four. Settling in Harlem, her mother, Alma Scott, opened a restaurant, took up the saxophone, and formed an all-women band.

Their apartment became a gathering spot for artists and musicians during the Harlem Renaissance when the neighborhood became the artistic center for Black Americans in New York.

Billie Holiday and Lester Young were among Scott’s regular guests and no doubt deeply influenced young Hazel Scott. But it was her mother who fostered her musical spirit and boldly brought her to audition at Juilliard when she was just eight — ignoring the school’s minimum age for entry at the time which was 16.

While studying classical music at Juilliard, she also absorbed boogie-woogie and blues from Fats Waller and Art Tatum. She would eventually become known for her modern renditions of vintage classics.

Scott played in her mother’s band and made her solo debut at the age of 15, playing after the Count Basie Orchestra at the Roseland Ballroom. Still only a teen, she hosted a radio show and performed on Broadway.

Then, as the intermission pianist for famous lounge singer Frances Faye, she found the signature act that would catapult her to fame.

Scott began to play up-tempo renditions of classical pieces by Chopin, Bach, and Rachmaninoff. Doing this was called “swinging the classics,” and it had been done before, but no one could do it quite like Scott.

Becoming The Darling Of Café Society

In 1938, a Jewish shoe salesman with no experience in nightlife opened a jazz club in Greenwich Village.

His name was Bernard Josephson, and he named his club Café Society, “the wrong place for the right people.” Unlike just about any other club in the city at the time, Café Society was fully integrated.

Audience members of all races sat at the same tables, danced together, and shared the stage. The club opened on New Year’s Eve with Billie Holiday singing her famously emotional song, Strange Fruit.

When Holiday left her engagement at Café Society three weeks early, she insisted that Hazel Scott take her place. At the age of 19, Scott took the stage — and became the “Darling of Café Society.”

Indeed, Josephson even opened a swankier branch of Café Society uptown where he could install Scott as the regular headliner.

Getty ImagesHazel Scott was best-known for modernizing classical pieces by the likes of Chopin and Bach.

Time Magazine wrote of her ability to modernize the classics:

“Classicists who wince at the idea of jiving Tchaikovsky feel no pain whatever as they watch her do it… Strange notes and rhythms creep in, the melody is tortured with hints of boogie-woogie, until finally, happily, Hazel Scott surrenders to her worse nature and beats the keyboard into a rack of bones.”

By now it was the 1940s, and though Scott was in high-demand even by white audiences, she had some demands of her own before agreeing to play. While touring the country, if she arrived at a venue that was denying Black people entry, she would refuse to play.

“Why would anyone come to hear me, a Negro, and refuse to sit beside someone just like me?” She insisted. Sometimes, she’d simply take her pay from the racist venue and leave.

Taking Hollywood By Storm

In the early 1940s, Hollywood came courting, but of course, Hazie Scott faced the challenges of pervasive racism in the studio system as well.

At Columbia Pictures, she demanded the final say in her wardrobe and in her musical numbers. She also insisted that she receive the same pay as her white counterparts. Josephson helped her negotiate a salary of $4,000 per week, which is about $60,000 by today’s standard. In comparison, Hattie McDaniel, who won an Oscar for her portrayal of Mammy in Gone with the Wind, was paid $700 per week.

Graphic House/Archive Photos/Getty ImagesScott surrounded by admirers, circa 1940.

Scott appeared in five films, including Something to Shout About, which featured original music by Cole Porter, and I Dood It! where she and another famous jazz musician of color named Lena Horne stole the show.

But it wasn’t long before Scott ran afoul of Hollywood during the filming of The Heat’s On.

It was 1943 and the United States was in the thick of World War II. Scott was to play the song The Caissons Go Rolling Along, a rah-rah patriotic number with Black soldiers breaking into dance with their sweethearts as they leave for the war.

Returning to her dressing room after rehearsal, Scott overheard the choreographer telling the costume designer to wipe oil and dirt on the women’s aprons because they were too clean.

Scott was livid, “I insisted that no scene in which I was involved would display Black women wearing dirty aprons to send their men to die for their country.” So she staged a strike. For three days, production stopped, costing the studio thousands of dollars.

Finally, the women were allowed to wear their own clothes. Scott had won the battle, but she had antagonized the head of Columbia Pictures, who vowed, “She will never set foot in another movie studio as long as I live.”

Leaving Music For The Pastor She Loved

Offscreen and offstage, Hazel Scott led an equally theatrical love life. She fell for Adam Clayton Powell Jr., the pastor of Harlem’s powerful Abyssinian Baptist Church, and the first Black man elected to the New York City Council. He was also married.

But when he met Scott, he was willing to risk his reputation in pursuit of her.

Their affair was open and scandalous, and the press had a field day when Powell was elected to Congress and brought Scott to the inauguration instead of his wife.

Eleven days after Powell’s divorce, he married Scott in what was to be one of the biggest celebrity weddings of 1945. Life Magazine covered the reception, which was attended by a who’s who of musicians, politicians, and artists. Two thousand onlookers gathered to catch a glimpse of the bride and groom. They were easily the most famous Black couple in America.

Getty ImagesPowell and Hazel Scott with their only child together, Adam Clayton Powell III.

Soon after the wedding, Powell asked Scott to stop working in nightclubs as he believed it was unsuitable work for the wife of a pastor. With mixed emotions, Scott agreed and gave up her lucrative weekly gig at Café Society. Instead, she began touring concert halls and found new fronts in her battle against racism.

She canceled a Presidential performance at the National Press Club because Black journalists were not allowed to be members. After a diner in Spokane refused to serve her, she sued and won a settlement of $250, which she donated to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

She also broke new ground in television.

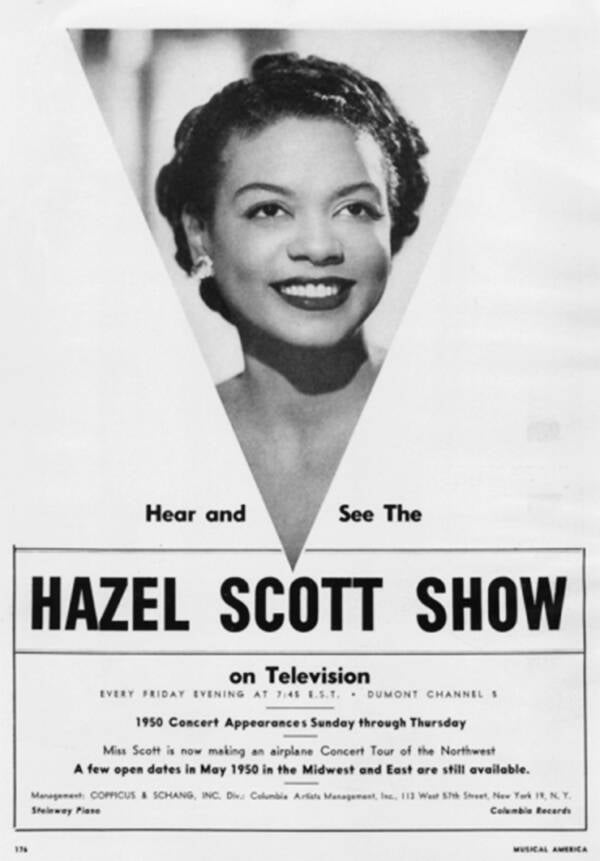

A maverick channel known as DuMont Networks offered her a 15-minute show that would run on Friday nights. In 1950, Scott became the first Black woman to host her own television show, The Hazel Scott Show, which was so popular that it was soon broadcast nationally three times a week.

Accusations Of Communism Destroy Hazel Scott’s Career

The Mel Powell Papers, Gilmore Music Library, Yale University.Photograph of Count Basie, Teddy Wilson, Hazel Scott, Duke Ellington, and Mel Powell in 1942.

As was the case with many powerful Black people in her time, Hazel Scott was eventually defamed by a political campaign against her.

The same year that she became the first Black woman to host her own show, Scott was blacklisted on the Red Channels, a right-wing paper that identified suspected Communists.

Despite the advice of her husband, she volunteered to appear before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) to clear her name. At the hearing, Scott condemned Red Channels for publishing names without verification and slammed the practice of blacklisting artists. Her name was splashed across newspapers in connection with the Communist scare, nonetheless.

Within three weeks, DuMont Network canceled her contract, and concert bookings became harder to come by. Unwilling to play in segregated halls and unable to perform in nightclubs because of her agreement with her husband, her opportunities became more and more limited.

Finally, she decided to go abroad.

The Final Decrescendo

Hazel Scott toured London, Paris, Greece, and Jerusalem. At first, Powell came along, unofficially acting as her manager. They moved through Europe like American royalty, living in lavish hotels where they entertained celebrity friends.

But behind the glamorous facade, their marriage fell apart. Powell later said that he was probably secretly jealous of his wife’s career.

Scott moved to Paris with their son. They divorced in 1960.

Wikimedia CommonsA marquee for the Hazel Scott Show, the first television program to star a Black woman.

By then, jazz was giving way to rock ‘n roll. Though Scott had been one of the highest-paid musicians in her time, she struggled to survive on jobs that were few and far between.

In 1967, she returned to America and faced a barrage of criticism for leaving just when the fight for civil rights had intensified.

She still managed to find work and played for devoted fans at the Cannes Film Festival, on the Queen Mary, at swanky hotel lounges, and small nightclubs. But then, in 1981, Scott died of pancreatic cancer just after landing a long-term gig in a club named after her.

“Any woman who has a great deal to offer the world is in trouble,” she once mused. “And if she’s a black woman, she’s in deep trouble.”

As a prominent jazz pianist and an outspoken crusader against injustice, Scott paved the way for Black women in television, movies, and on the stage. She deserves an exalted place in the pantheon of jazz legends and in the hall of America’s boldest civil reformers.

Now that you’ve learned about Hazel Scott, hear these lost Ella Fitzgerald tapes that resurfaced in Berlin. Then, find out how Glenn Miller went from musical icon to missing in action during World War II.