Dr. John Harvey Kellogg used a host of bizarre methods to prevent masturbation and cleanse his patients’ colons at the Battle Creek Sanitarium in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Getty ImagesAs a leading figure in the American hygiene movement, John Harvey Kellogg espoused a holistic approach to health and wellness, but he also believed genital mutilation was an appropriate anti-masturbation measure.

For a simple American breakfast staple, “Kellogg’s Corn Flakes” has a surprisingly sordid past.

John Harvey Kellogg, who invented the cereal with his brother, was a sort of prophet of hygiene in 20th-century America. But although he championed nutrition and a holistic approach to the overall health of the average American, Kellogg was also a staunch eugenicist and launched a violent anti-masturbation campaign that saw the genitals of young boys and girls mutilated.

So how did such a controversial scientist become the baron of breakfast in homes across America?

John Harvey Kellogg And Religious Medicine

John Harvey Kellogg was born at the onset of America’s hygiene revolution on February 26, 1852, in Tyrone, Michigan. This was the same year that the nation’s first flushing toilet was patented and just eight years before the invention of Listerine, which was originally used as an antiseptic.

At the same time, America saw a rise in temperance groups like the Seventh-Day Adventists, whose main campaigns were against alcohol and sex. This combination of extreme hygiene and abstinence heavily influenced Kellogg’s theories about health and wellness.

University of MichiganWill Keith Kellogg never mended his relationship with his brother John Harvey, which was irreparably damaged during their legal battle for the rights to use their last name on their respective cereals.

Kellogg was one of 11 kids in a family of devout Seventh-Day Adventists, and his most notorious relationship would be with his younger brother, William Keith Kellogg, who John Harvey notoriously sidelined as his intellectual inferior.

In 1856, the Kelloggs moved to Battle Creek, Michigan, which was the mecca for Seventh-Day Adventists at the time. Because they were so confident that Christ’s second coming — and the end of the world — was inevitable, none of the Kellogg children were really formally educated. John Harvey Kellogg, however, voraciously educated himself.

When he earned his medical degree in 1875, he had already formed a holistic model for healthy living that hinged on the innovations of America’s hygiene movement and his religious faith, which he dubbed “biologic living:”

“All the inventions and devices ever constructed by the human hand or conceived by the human mind, no matter how delicate, how intricate and complicated, are simple, childish toys compared with that most marvelously wrought mechanism, the human body.”

Kellogg deeply revered the human body, which he referred to as “the living temple,” and took a holistic approach to supporting it that was based as much on nutritional science as it was on religious extremism.

He espoused vegetarianism, prohibition, and abstinence, and he called any action outside of these things, “self-pollution.” In sum, Kellogg was invested in total cleanliness — of the body and the spirit — and he concocted some bizarre ways of achieving it.

In 1877, Kellogg took over the Battle Creek Sanitarium, a health spa for Seventh-Day Adventists, and remodeled the facility based on his ideals for optimal living.

In a nation where the average life expectancy was 41 years and city streets were literally piled with human feces, the Sanitarium emerged as a beacon of wellness. The facility took off. Within a decade, it went from treating 300 patients per year to almost 1,200.

Meanwhile, Kellogg had taken a particular interest in cleaning up America’s breakfast routine.

A Cereal So Bland It Hampers Sexual Desire

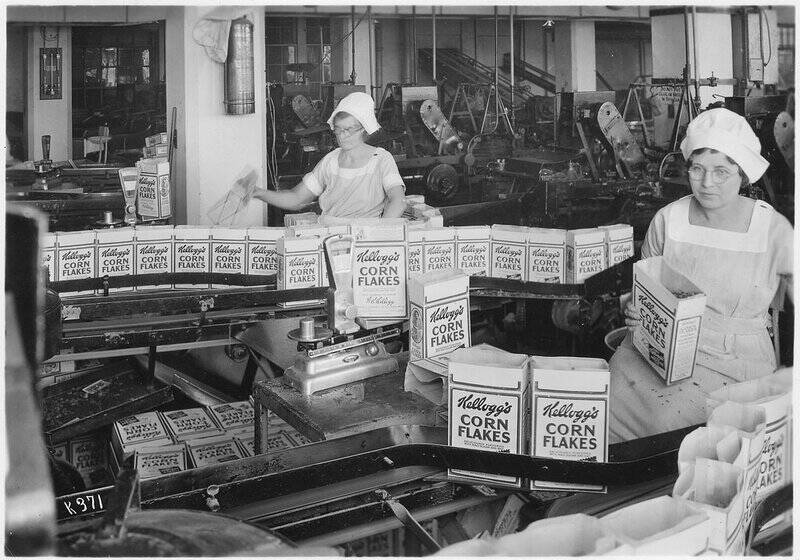

Getty ImagesWomen inspect filled boxes of Corn Flakes in the Kellogg Company factory in 1934.

The average American breakfast in the 1880s consisted mostly of meat in various forms: cold, jellied, smoked, salted, fried in leftover fat. Any non-meat alternatives, like grains or oats, were time-consuming, which made breakfast a burdensome meal both in calories and preparation.

In keeping with his desire for total cleanliness, John Harvey Kellogg encouraged his patients to eat sterile, healthy foods that he believed all primates should eat: mostly nuts and grains, and yogurt. And for years, he and his brother William worked tirelessly to perfect a low-maintenance, grain-based breakfast cereal.

Their first attempt was made of baked whole graham biscuits that were then crumbled into bits. They called this “Granola,” but were ultimately unsatisfied with the result. Finally, they settled on a flaked wheat cereal they originally dubbed Granose. In 1902, they remanufactured the product out of maize and called it corn flakes.

But by this time, John Harvey grew disinterested in the enterprise, so William — the real business brain behind the operation — bought his brother’s share of corn flakes and opened the Battle Creek Toasted Corn Flake Company in 1906.

He proved to be a marketing genius and launched an uber-successful campaign telling consumers to “wink at your grocer and see what you get,” which resulted in a free sample of corn flakes.

Meanwhile, John Harvey continued to manufacture and sell Granose out of his own company by the name “Kellogg’s” and sued his brother over who got the rights to use their last name. William sued him back.

After years of fighting, during which corn flakes became all the more popular, William won the rights to use his own name for Kellogg’s Corn Flakes in 1920.

“I am not after the business,” Kellogg said of the affair. “I am after the reform.”

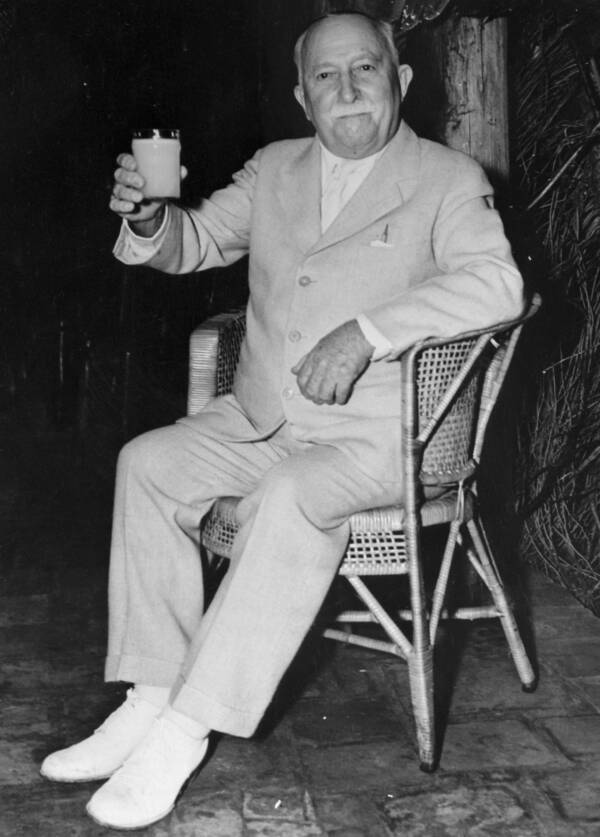

Getty ImagesKellogg in 1938, aged 86.

To his point, the saga of corn flakes, more importantly, represented to John Harvey the battle against one of life’s deadliest vices: masturbation. As a meticulously manufactured “clean” food, Kellogg had intended for corn flakes to rid people of their carnal desires.

Terrified and disgusted by sex nearly all his life — he never even consummated his own relationship with his wife — Kellogg launched a violent pseudoscientific anti-masturbation crusade. He equated fondness for spicy foods, round shoulders, and “boldness” with signs of a chronic masturbator. He concluded that “such a victim literally dies by his own hand.”

Kellogg encouraged parents to tie their children’s hands to their bedposts or to circumcise their teenage boys. An even more aggressive tactic saw the foreskin of a young man’s penis sewed shut to prevent erections. For young girls, he recommended pouring carbolic acid on their clitorises.

Of course, it was Kellogg’s hope that a purer diet, provided by his Corn Flakes, might suffice as a less gruesome method of controlling children’s sexual desire.

John Harvey Kellogg’s Bizarre Wellness Tips

Library of CongressJohn Harvey Kellogg ran the Battle Creek Sanitarium, pictured here, until his death in 1943. During that time, he invented peanut butter and several nut-based meat alternatives.

In addition to creating a breakfast cereal so bereft of flavor he believed it would erase any desire, Kellogg’s biggest project was his wellness retreat at the Battle Creek Sanitarium, which he led until his death in 1943.

The facility introduced thousands of Americans to the importance of exercise, bathing, and occasional douching. Kellogg even invented the mechanical horse for indoor exercise. At its height, the Sanitarium sprawled across 30 acres and was dubbed one of the “premier wellness destinations” in the United States.

To crowds of wealthy and unwell Americans learning about hygiene for the first time, Kellogg basically became one of the nation’s first “wellness gurus,” and he managed tens of thousands of patients. Among them were retailer J.C. Penny, Henry Ford, Thomas Edison, Amelia Earhart, and President William Howard Taft.

But Kellogg also concocted some more incongruous health methods. For instance, he encouraged his patients to get multiple enemas a day — and invented an enema machine that could run 15 quarts of water through the bowels in a matter of seconds. Kellogg himself received an enema at breakfast and lunch.

Kellogg also encouraged his patients to consume a daily pint of yogurt — one half through the mouth and the other through the anus. Strange though that may sound, it was actually an early way of receiving probiotics. He also patented a chair that shook patients so violently they involuntarily defecated.

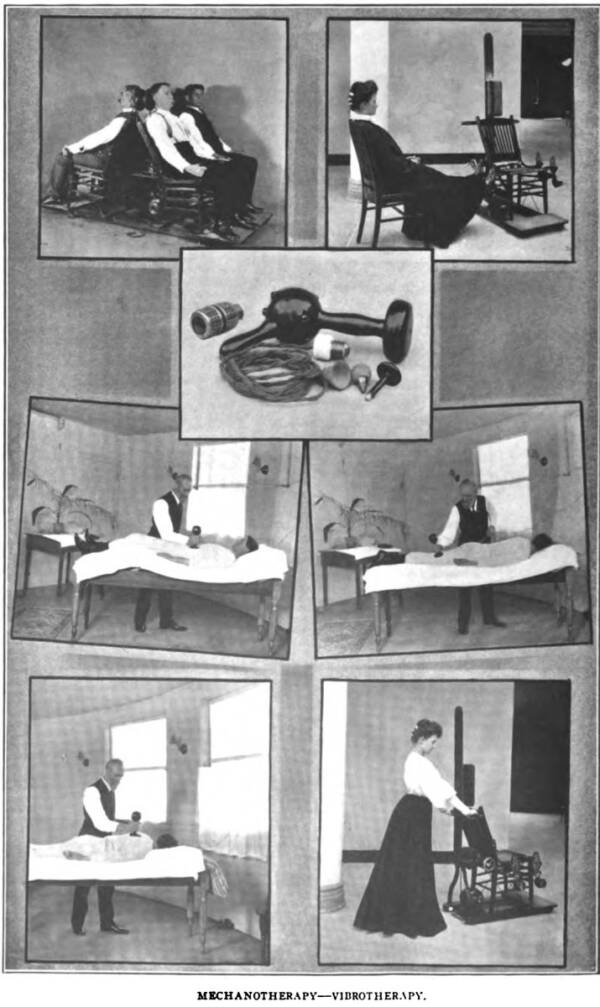

Public DomainThis pamphlet for the Sanitarium shows some of the many treatments patients could receive there, from hydrotherapy to artificial sunlight baths.

But for all those progressive — albeit bizarre — beliefs about nutrition and wellness, he had equally dangerous ones. A staunch eugenicist, Kellogg advised against “racial mixing” and instead posited a registry that kept track of people’s medical records so that “racial thoroughbreds” could be introduced to each other before marriage.

He was also in favor of the forced sterilization of criminals and organized the first Race Betterment Conference, which was basically a fair for eugenicists. The conference even hosted so-called Better Baby contests, during which white infants were judged and awarded on the basis of their “breeding.”

At the same time, however, Kellogg rejected segregation at his Sanitarium, where he trained doctors and nurses of color. And Kellogg treated legendary abolitionist Sojourner Truth at the Sanitarium, once reportedly grafting some of his own skin onto her leg to treat an ulcer.

A Tumultuous Personal Life And Complicated Legacy

Kellogg ran the Sanitarium until his death in 1943, before which he opened a second health spa in Florida. He patented four medical devices, including an artificial sunbath machine and a peanut-based meat alternative called Nuttose.

With his wife Ella Ervilla Eaton, he fostered 42 children, seven of whom he legally adopted. They never had any biological children of their own.

John Harvey Kellogg also never mended his relationship with William. On his deathbed, however, he did pen a letter of amends that was seven pages long. “I earnestly desire to make amends for any wrong or injustice of any sort I have done to you,” he wrote.

But his secretary, for whatever reason, chose not to deliver the letter. William, therefore, didn’t learn that his older brother had reached out until it was too late.

Unusual though some of his wellness treatments seemed, Kellogg must have been doing something right: He died at the ripe old age of 91.

John Harvey Kellogg’s legacy is a complicated one. Though he brought nutrition and hygiene to the forefront of American living as one of the nation’s first wellness gurus, he also espoused dangerous and violent ideas about sexuality and race.

Concerned as he was with the betterment of humanity, he primarily focused on the white race, but he devoted his life to progress, nonetheless. Perhaps his contentious invention of Corn Flakes, a nutritious cereal with a dangerous idea behind it, best encapsulates his duality.

After this look at John Harvey Kellogg, the man who invented Corn Flakes so people would stop touching themselves, learn about another complicated physician, J. Marion Sims. Then, discover the terrifying yet necessary job of medieval plague doctors.