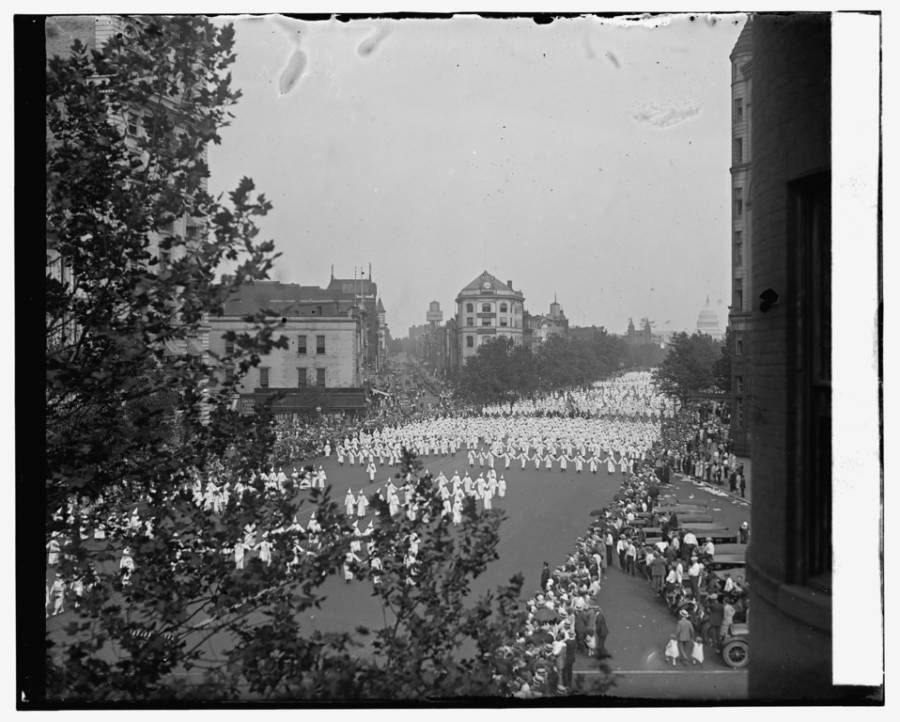

In August of 1925, 60,000 Ku Klux Klan members marched to the White House to display their ever-increasing numbers across America.

When people talk about the March on Washington, they think of Martin Luther King Jr. and the civil rights movement.

But there was another march -- 40 years earlier -- that history's forgotten, one with a much more hateful motive.

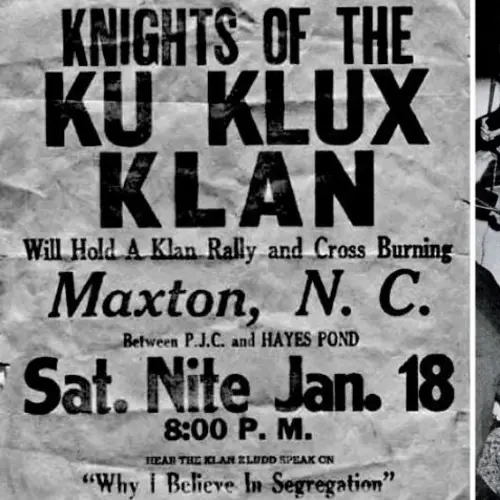

It was 1925, the height of the Ku Klux Klan's popularity. Its membership had topped 3 million and as Jewish and other European World War I refugees flooded in, the Klan was only gaining momentum for its nationalist message.

D.C. officials debated whether or not it was a good idea for them to give the marchers permission for their planned August 8 event, they eventually acquiesced -- as long as participants didn't wear their signature masks.

"The Commissioners could not discriminate between applicants for the right to use the streets for parading purposes, and their action in granting this permit was not only justified but required," a statement justifying the city's decision read.

The "konklave" took place twice -- 1925 and 1926 -- and drew more than 50,000 marchers.

Newspapers across the country reacted differently to the event:

"Oh say not so," said one in Maryland of the country "quivering in excited anticipation of 100,000 ghostly apparitions wafting through the streets of the national capital to the stirring strains of the 'Liberty Stable Blues.'"

When rumors spread that the parade had been canceled, though, another Baltimore paper expressed dismay.

"Darn! There goes a-glimmering the thrill of a lifetime," its editors wrote.

A paper in Syracuse said that the Klan should be allowed to demonstrate, if only due to the fact that it would spread national awareness.

"Ku-Kluxism is least harmful and menacing when the sun shines on it," the staff printed. "Only in the dark can it make trouble. For that reason, we say let them parade."

Though locals were concerned about the city's safety during the demonstration, no violence occurred. But that doesn't mean it wasn't disturbing.

"Thousands of white-robed figures, old and young, had congregated east of the Capitol, flaunting American flags and banners emblazoned with the mystic symbols of the Klan, long before the hour set for the unique parade," the Washington Evening Star wrote. "There were men in white satin robes: they were the kleagles, dragons kilgrapps and other high officers in the various State units."

The other attendees wore noticeably cheaper outfits and mingled with their families throughout the crowd.

Journalists admitted that it surpassed expectations for size.

"The Klan put it all over its enemies," the New York Sun wrote. "The parade was grander and gaudier, by fair than anything the wizards had prophesied. It was longer, it was thicker, it was higher in tone."

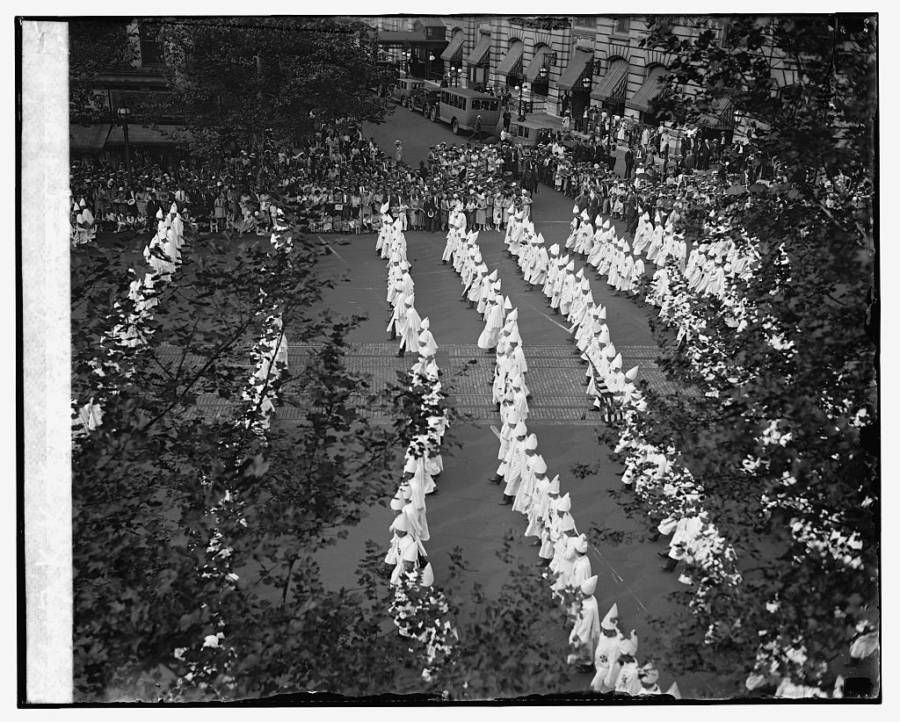

Bonded by racism, the men walked shoulder to shoulder.

They formed moving white K's and crosses visible from the sky and carried American flags -- suggesting a vision for the country at odds with the guiding mantra we've since embraced, that "all men are created equal."

The men flooded into the capitol from across the country. They wore crosses and held flowers. They held hands and stood in formations that were frightening in their order and complexity -- suggesting a level of organization capable of influencing a country.

However, it's comforting that the walk of hate was eventually superseded by people marching for a unified country.

Five times as many people would walk the same streets during 1963's March on Washington. Black and white, men and women, rich and poor gathered to listen to a message of inclusion.

"When we allow freedom ring, when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God's children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual," Martin Luther King would bellow. "'Free at last! Free at last! Thank God Almighty, we are free at last!'"

After seeing these photos from the KKK march on Washington, read about the black man who convinced 200 racists to leave the KKK by befriending them. Then, learn about the famous members of American politics you didn't know were in the KKK.