Under the code of omertà, anyone who spoke to the police was marked for torture and death — and so were their families.

To countless Mafiosi, ‘Ndranghetisti, and Camorristi, the rule by which they lived and died was simple and summed up with a single word, omertà: “Whoever appeals to the law against his fellow man is either a fool or a coward. Whoever cannot take care of himself without police protection is both.”

This code of silence towards law enforcement forms the bedrock of criminal ethics among the organized crime clans of Southern Italy and their offshoots. Under this seemingly ironclad ethos, “men of honor” are strictly forbidden to reveal details of the criminal underworld to the state, even if it means they must go to prison or the noose themselves.

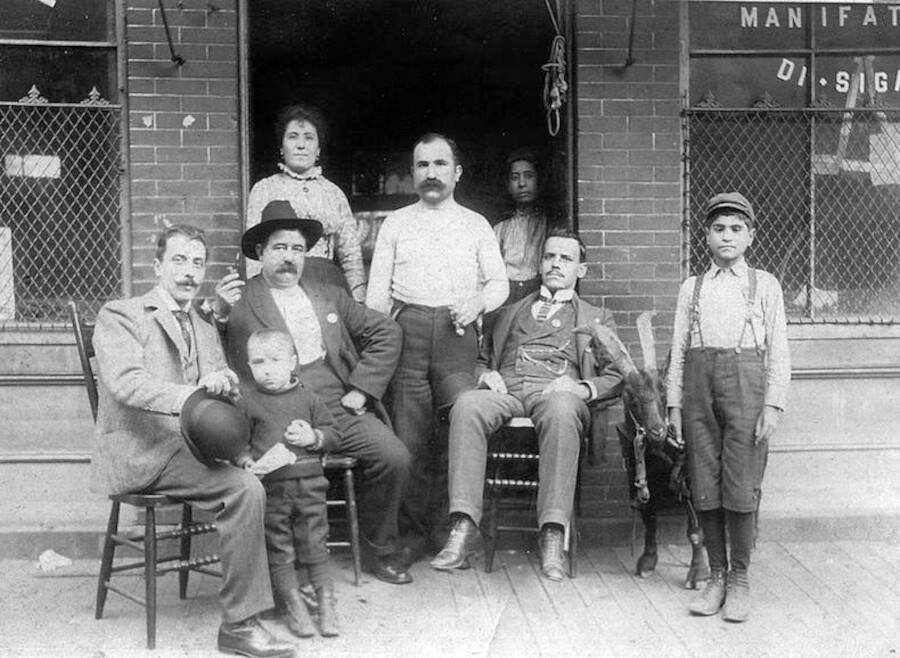

Wikimedia CommonsGenerations of Italian criminals and their descendants clung fiercely to omertà, the code of silence — until it was no longer convenient.

Despite its supposed sacredness, the history of omertà contains countless stories of its violation, as well as its protection. This is how an ancient practice became one of the most infamous features of modern organized crime.

The Shadowy Origins Of Omertà

Exactly when and where omertà arose is lost in the murky, secretive depths of Mafia history. It’s possible that it descended from a form of resistance against the Spanish kings who ruled over Southern Italy for over two centuries.

Public DomainAs the Mafia grew in the lawless atmosphere of 19th-century Sicily, so too did omertà.

More likely, however, is that it was adopted as a natural consequence of early criminal societies’ outlawry. By the beginning of the 19th century, the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies was crumbling. In the ensuing chaos, bands of brigands began to function as private armies for those who could pay. This was the birth of the Mafia and the dawn of the culture that paid tribute to them.

After northern and southern Italy merged into a single kingdom in the 1860s, the reborn state built a new court system and police forces. When these institutions were extended to the south, organized clans found themselves facing powerful new rivals.

In response, the uomini d’onore, or “men of honor,” adopted a simple, brutal principle: never talk to the authorities, under any circumstances, about criminal activities of any kind or committed by anyone, even mortal enemies. The penalty for violating this rule was, without exception, death.

How Omertà Came To The United States

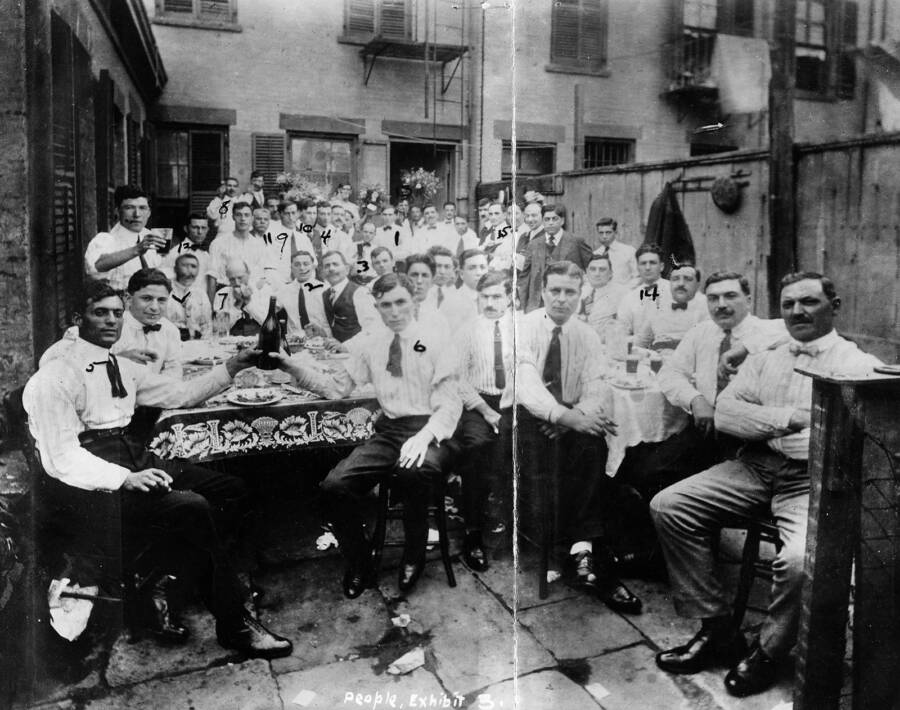

Wikimedia CommonsCriminal societies like the Camorra imported omertà to the United States, frustrating early attempts to penetrate Italian organized crime.

Under the reunified Kingdom of Italy, the southern provinces were still desperately poor, and many chose to emigrate in search of prosperity. But along with the many peaceful, law-abiding folk who traveled abroad came the men of honor.

In many North American cities, Italian immigrants were only grudgingly accepted, and many felt they couldn’t count on local police or governments to represent or protect them.

The poor neighborhoods where they lived proved fertile ground for new Mafia clans to flourish. And the communities from which they arose — and on which they preyed — cooperated with the code of omertà, often as a matter of pride.

For nearly 100 years, the American Mafia was a closed book to police, who could never manage to coerce or convince mobsters to give them a look into the secretive families. That all changed in 1963.

Joe Valachi’s Historic Betrayal Of The Genovese Family

A Mafioso almost from childhood, Joseph Valachi eventually became a trusted soldier for mob boss Vito Genovese. But in 1959, he and Genovese were convicted of narcotics trafficking, an increasingly common mob earner at the time, as was Genovese after the chaotic Apalachin Meeting.

Frank Hurley/New York Daily News via Getty ImagesJoseph Valachi was the first American Mafioso to break omertà, opening the floodgates for later informants.

While imprisoned in 1962, Valachi killed a man he believed to have been an assassin sent by Genovese. To escape the death penalty, he did what had, until then, been unthinkable for any mobster — he agreed to testify before the Senate.

In a series of televised appearances, Valachi introduced the American public to what had long been secrets known only to the Mafia and the Italian-American community. He revealed that the organization he belonged to called itself Cosa Nostra, “our thing.”

Valachi told the Senate committee that families had a paramilitary structure, that they had influence at every level of society, and that a blood oath of silence bound each fully-initiated “made man”. That code was called omertà, he said, and he was violating it.

Joseph Valachi’s testimony heralded the dawn of a new era in American anti-Mafia efforts. With the breaking of omertà, more and more Mafiosi would step forward in the years to come as federal law enforcement officials steadily hemmed in the power of the criminal families.

Breaking The Code Of Silence In Italy And America

Mondadori Portfolio via Getty ImagesGiovanni Falcone (left) and Paolo Borsellino (right) led a groundbreaking campaign against the Mafia during the 1980s. Both were later murdered in revenge.

Across the Atlantic, however, Italian crime families remained silent. The Sicilian Mafia, the Calabrian ‘Ndrangheta, and Campanian Camorra all held far more power in their respective territories than the Americans. And they seemed to be able to kill and extort indiscriminately and with impunity as Italian politicians and police stood by.

However, not all public officials were complacent or complicit, and not all Italian gangsters were so committed to omertà as they might have the public believe.

Judges Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino hadn’t set out to bring down organized crime. However, in the course of their work, they became aware of the Sicilian Mafia’s true power, wealth, and extreme violence and cruelty. In the years-long crusade that followed, they put hundreds of Mafiosi behind bars.

But their biggest break came when Tommaso Buscetta, a high-ranking mobster, agreed to testify after a particularly vicious Mafia clan started targeting his family, “systematically wiping them out.” In 1982, Mafia hitmen murdered two of his sons, his brother, a brother-in-law, a son-in-law, four nephews, and numerous friends and allies. He broke omertà the following year.

In an unprecedented testimony, Buscetta revealed a trove of mob secrets to Falcone, Borsellino, and other prosecutors. They knew the risks — Buscetta warned them that “First, they’ll try to kill me, then it’ll be your turn. They’ll keep trying until they succeed.” And sure enough, both were killed in separate bombings in 1992.

Jeffrey Markowitz/Sygma via Getty ImagesSammy “the Bull” Gravano became one of the most notorious figures in the history of organized crime when he betrayed Gambino crime family boss John Gotti.

But on both sides of the Atlantic, the damage was done. Buscetta’s testimony dealt a severe blow to the Sicilian families. In the United States, Lucchese family associate Henry Hill’s testimony led to dozens of convictions.

The final nail in the coffin for omertà, at least as far as the authorities and the public were concerned, came in 1991. In November of that year, Gambino family underboss Salvatore “Sammy the Bull” Gravano, right-hand man to John “the Teflon Don” Gotti, agreed to turn state’s evidence.

The information he gave federal investigators put a definitive end to the Mafia’s last era of public celebrity and showed that omertà was only the law for mobsters so long as it was convenient.

After learning about the true history of the Mafia’s code of silence, find out more about the death of Frank DeCicco, the mob underboss murdered for his role in the rise of John Gotti. Then, take a look at some of history’s most infamous mob hits in these disturbing photos.