The Mafia had operated with near-immunity until Joe Valachi spilled his guts to the U.S. Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs, the Justice Department, the FBI, and on a radio broadcast.

One key principle governed the Mafia’s world of organized crime: the code of silence known as omertà. No one talked to external parties or authorities about the heinous crimes that its members committed. As a result, despite law enforcement’s best attempts to incriminate Mafia leaders, these “wise guys” literally got away with murder.

That is until mafioso Joe Valachi opened his mouth.

On September 25, 1963, Joe Valachi became the first mafioso to break the mafia’s secret code and publicly admit to its existence.

In the 1960s, Valachi publicly disclosed the Mob’s dirtiest secrets heretofore only known by organized crime insiders in a public trial as a witness for the government.

He divulged its most intimate affairs before the papers and cameras. As a result, organized crime saw an increase in its membership informing on one another. This spelled the beginning of the end to life as they knew it.

The Alpha And Omega Of Omertà

The Mafia had valued the concept of silence since its origins in Italy and Sicily. Back in the “old country,” small militias or gangs managed to elude the authorities by keeping quiet and refusing to snitch on their fellow gangsters — even their rivals. The mafiosos established a universal policy that meant enemies and allies alike protected one another in the face of law enforcement and held each other to standards that incorporated conceptions of brotherhood and honor.

In Italian, this policy was called omertà. When Italian organized crime came to America, omertà, too, took root in American criminal culture.

This complicated things for American law enforcement. They knew that mobsters were smuggling alcohol and drugs, murdering people, and running rackets, but if they couldn’t flip witnesses and get mobsters to testify on their cohorts, they had little verbal evidence.

According to Mafia historian Selwyn Raab who told Rolling Stone, if rats threatened to flip:

“If you became a rat or you in any way betrayed the Italian or Sicilian mafia, it wasn’t just you, but anybody in your family could be victimized[…] method to prevent people from becoming informers and betraying the Mafia. There’s stuff on tapes in which they talk about it – ‘If my kids have to suffer, why shouldn’t the rat’s kids have to suffer?'”

When brought to the witness stand, Mafiosi would often invoke the Fifth Amendment and refuse to self-incriminate. As a result, law enforcement got next to nothing when calling criminals or their associates to testify.

How was American law enforcement, then, supposed to bring down the Mob when its members refused to talk?

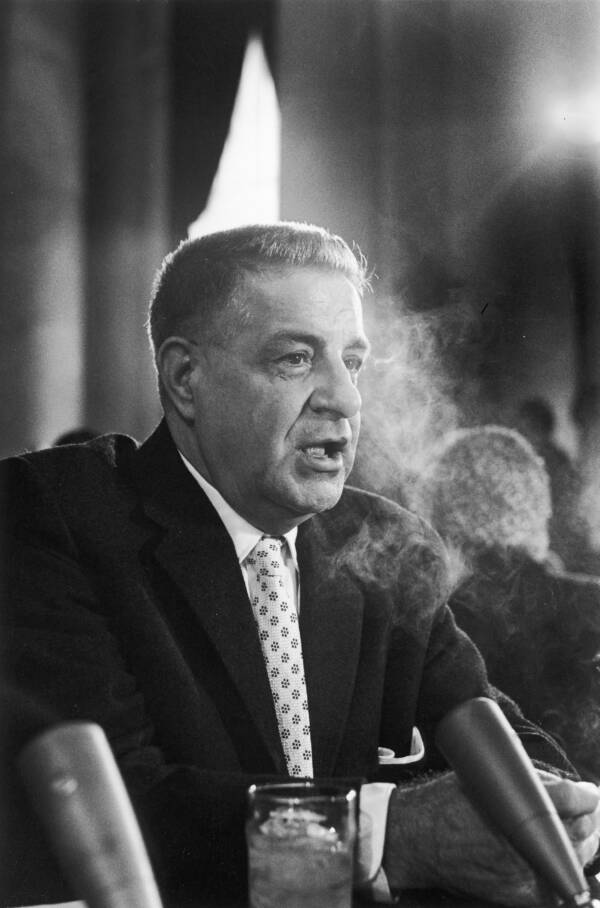

Washington Bureau/Archive Photos/Getty ImagesBefore Joseph Valachi testified before the Senate Rackets Committee, in 1963, the Mafia had a strict code of honor by which no one spoke to law enforcement of their activities.

Enter Joe Valachi.

While Locked Up, Joe Valachi Opens Up

Joe Valachi, or Joseph “Cago” Valachi, was just a low-level New York gangster. He ran gambling rackets and peddled narcotics for a time before working under the Genovese crime family. Born in East Harlem, New York, on September 22, 1904, Valachi was destined for crime from birth. His parents were poor Italian immigrants and his father a violent drunk.

His first foray into crime began behind the wheel of the getaway car for petty thieves known as the “Minutemen” — because they could burglarize and be off within minutes. Valachi earned a rep for himself as a speedy and efficient criminal driver.

Frank Hurley/New York Daily News via Getty ImagesMobster Joseph Valachi waits to testify at Senate Rackets Committee.

Finally arrested in 1921, Valachi got out in ’23 in time to see his crew of Minutemen shacked up with a different driver. Valachi then joined up with the Reina crime family, now known as the Lucchese crime family, as a “soldier” in the crime war between bosses Joe Masseria and Salvatore Maranzano. Valachi stood behind Maranzano as a bodyguard until both Masseria and Maranzano were shot and killed by Charles “Lucky” Luciano — who consequently took the helm on all Five Families.

Joseph Valachi worked beneath the Luciano crime family which later became the Genovese crime family until he was eventually convicted of drug dealing in 1959 — though not of dozens of murders he’d likely committed.

In 1962, mob boss Vito Genovese suspected that Valachi had actually ratted on his Mafia colleagues. He ordered a hit on him. Terrified, Valachi beat to death a man he believed to be a Genovese assassin in jail. As it turns out, he’d gotten the wrong guy.

Meanwhile, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy was after the Mafia with guns blazing. He wanted the Department of Justice to bring down organized crime at any cost. His number one target was none other than the Italian Mafia, but RFK would need someone within the organization to help him out. RFK’s previous efforts to topple Mafia kingpins were not as successful as he’d hoped because mafiosos so strictly held to omertà.

But in a terrified and incarcerated Valachi now facing a life sentence for murder, Kennedy thought he found the perfect ally.

Wikimedia CommonsRobert F. Kennedy in 1962.

Valachi was desperate to save himself and so he turned to the only people he thought could stop Genovese: the federal government. In exchange for breaking the most important code of honor within the Mafia and pleading guilty to a charge of second-degree manslaughter, Joe Valachi agreed to give up all his information on Mafia activities.

The Joseph Valachi Hearings

The Feds were amazed. As Selwyn Raab noted in his book Five Families, for the first time, the American authorities had first-hand information about the way the Mafia operated, their codes of honor and silence, and its structure. Valachi even told the authorities the Mob’s nickname for itself, the “Cosa Nostra,” Italian for “our thing.”

Now that they had this info, the Feds could take their pursuit of justice to the public. They organized a hearing in which Valachi would testify publicly to the unknown of the underworld.

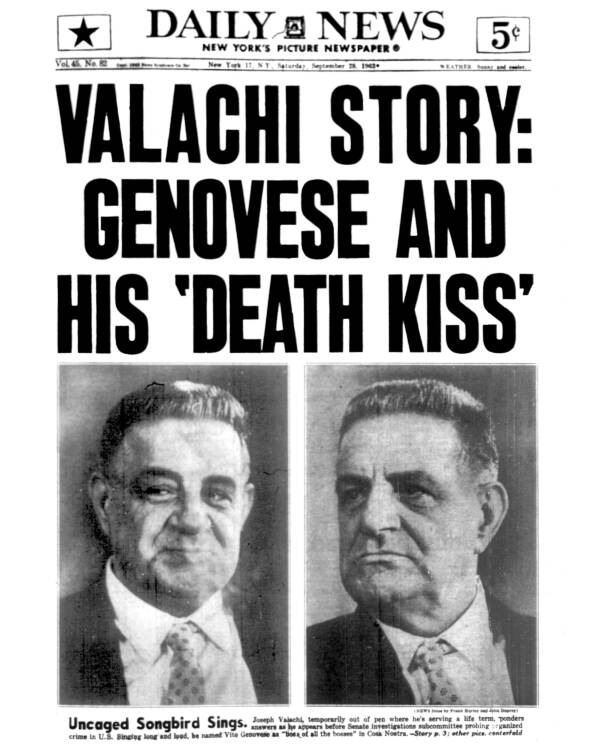

NY Daily News Archive via Getty ImagesDaily News front page on September 28, 1963. Joseph Valachi, temporarily out of jail where he’s serving a life term, “Singing long and loud…named Vito Genovese as ‘boss of all the bosses’ in Cosa Nostra.”

In the fall of 1963, the Senate Government Operations Permanent Investigations Subcommittee trotted out its star witness, Valachi, to describe the Mafia’s inner workings.

This of course, also worked to show off all the progress Kennedy had made in taking down organized crime. Kennedy hailed the testimony the “biggest single intelligence breakthrough yet in combatting organized crime and racketeering in the United States.”

During the hearings, which were broadcast nationwide, Valachi said he became a Mob member 30 years earlier. His initiation involved driving the getaway car for an underworld hit.

He outlined the structure of the organization, how each family had a boss with underbosses and soldiers beneath that. Valachi ratted out the leaders of the Five Families of New York. Specifically, he noted that Genovese was the “boss of all bosses,” a term with lots of Mafia history behind it.

When asked why he never left, Joseph Valachi replied, “Once you’re in you can’t get out. You try, but they hunt you down.” However, he knew next to nothing about the Mafia outside of New York and said he never even heard of Omaha, Nebraska.

Joe Valachi appeared otherwise reliable. William G. Hundley, former special assistant to RFK and Chief of the Organized Crime and Racketeering Section of the Department of Justice, said:

“The information that Valachi was giving to the Bureau of Narcotics originally about ‘Cosa Nostra’ and the family and everything like that which I was giving to the FBI, this was being corroborated. The truth of it was being corroborated by what the FBI was picking up on all these bugs, so they knew that the fellow was telling a reliable story.”

For the first time, the federal government had a willing witness who outlined the ins and outs of a deadly criminal organization they had for years struggled to prosecute. But in exchange for his testimony, Valachi was neither freed nor put into Witness Protection.

He received an air-conditioned prison suite in El Paso, Texas, (which was actually formerly the suite reserved for those inmates about to go to the electric chair) but never regained his former bravado. After attempting suicide at least once, Joseph Valachi died in 1971.

How The Valachi Hearings Changed Everything

Getty ImagesFormer gangster Joseph Valachi testifies before a Senate Subcommittee.

The so-called Valachi hearings broke new ground for both the Feds and the Mafia. Now, the Feds knew how the enemy operated. Even though they couldn’t convict mobsters for most of the crimes Valachi had spoken of because they were past their statute of limitations, Valachi had nonetheless helped them to indict hundreds.

Further, no longer could anyone deny that the Mafia existed — and not only did it exist, but it thrived. The public could see definitively now just how pervasive its influence was from bribing judges to organizing labor rackets.

Where mobsters had previously been able to count on omertà, now they could not be sure they could trust anyone to keep quiet. In fact, mobsters who were in danger of going to jail were looking for ways out of prison. In exchange for reduced or commuted sentences, more and more flipped and began to testify to the Mafia’s secret activities.

One of the most famous cases of ratting was that of Sammy “the Bull” Gravano, an underboss in the Carlo Gambino clan who turned on John Gotti and spilled the beans about the dozens of murders that his boss had committed.

STEVEN PURCELL/AFP/Getty ImagesSalvatore “Sammy the Bull” Gravano, a former member of the Gambino family, prepares to testify in 1993.

In a 2001 article for Time, journalist Richard Lacayo wrote that it was the largest and most damning such testimony against a Mafiosa since Valachi’s own remarks in 1963.

As yet more high-ranking mobsters began to break omertà, the code of silence’s power weakened. Thus, the stranglehold bosses held on their underlings or soldiers weakened, too. In a 2000 Los Angeles Times article, reporter Larry McShane quoted ex-New York boss Bill Bonanno as saying “things have completely changed.”

“Bonanno, author of the recent mob memoir Bound by Honor, says government informants — with the exception of the infamous Joe Valachi — were nonexistent until the Mafia’s values began breaking down in the 1970s. ‘I can’t think of anybody who ever testified for the government, not in our family,’ says Bonanno, who quit the family business in 1968. ‘There was no need for it.'”

Joe Valachi’s Legacy/h2>

Joe Valachi’s story was later immortalized in the 1972 film The Valachi Papers starring Charles Bronson. The movie closely followed the mobster’s 1968 biography by Peter Maas of the same name.

Thanks to the precedent set by Valachi, Mafia culture has since changed. Perhaps the mobster didn’t think his testimony was enough to change the very core of the mafia, perhaps he did not consider any consequences beyond saving his own behind. Or maybe Valachi believed that the Mafia was just too big to fail, no matter what was said against it.

In his own words, “Nobody will listen. Nobody will believe. You know what I mean? This Cosa Nostra, it’s like a second government. It’s too big.”

After this look at the mob’s first turncoat, Joe Valachi, read all about the Mafia’s last gasp of glam in the 1980s. Then, dive into the story of Cudjo Lewis, the last slave brought to the United States.