During Operation Paperclip, the records of premier German scientists were expunged so that they could secretly work in American labs to give the U.S. a leg up over the Soviets in the Cold War.

In the immediate wake of World War II, the Allies were widely venerated for their role in ending the reign of the Third Reich. But the Allied powers also made controversial decisions in secret that were kept classified for decades. Perhaps their most contentious action was the creation of Operation Paperclip, a covert intelligence project that brought over 1,600 Nazi scientists to the United States for research.

At the end of the war, the Allies scrambled to collect German intelligence and technology that may otherwise fall into the hands of the Soviet Union. As an impending Cold War threatened to destroy the hard-won peace, the United States granted a slew of Nazi scientists immunity for their war crimes so that they could work in their labs instead of in Russian ones.

Though these scientists were responsible for such milestones as Apollo 11’s Moon landing, was America justified in its decision to pardon war criminals in exchange for a political advantage?

The Osenberg List And The Depth Of Nazi Research

Despite numerous costly efforts, from the Siege of Leningrad to the Battle of Stalingrad, Nazi Germany failed to beat back the U.S.S.R. as World War II wound down. As the Reich’s resources neared depletion, Germany became desperate for a new strategic approach against the Red Army.

Thus, in 1943, Nazi Germany collected its most invaluable assets — scientists, mathematicians, engineers, technicians, and 4,000 rocketeers — and stationed them all together in the Baltic seaport of Peenemünde in northern Germany to develop a technological defense strategy against the Russians.

Wikimedia CommonsKurt H. Debus, a former V-2 rocket scientist who became a NASA director, between U.S. President John F. Kennedy and U.S. Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson.

Werner Osenberg, the head of Germany’s Wehrforschungsgemeinschaft (or Defense Research Association), was responsible for determining which scientists to recruit by creating an exhaustive, thoroughly-researched roster. Scientists had to be considered sympathetic to or at least compliant with Nazi ideology in order to be invited. Naturally, this index came to be known as the Osenberg List.

Meanwhile, the U.S. had become increasingly more aware of the Nazis’ covert biological weapons program and, according to Annie Jacobsen’s 2014 book Operation Paperclip, the discovery of these scientific efforts shocked the U.S. into action.

FlickrPresident Truman signing the Atomic Energy Act in 1946. Meanwhile, 1,600 Nazi scientists were being recruited into the U.S.

“They had no idea that Hitler had created this whole arsenal of nerve agents,” explained Jacobsen.

“They had no idea that Hitler was working on a bubonic plague weapon. That is really where Paperclip began, which was suddenly the Pentagon realizing, ‘Wait a minute, we need these weapons for ourselves.'”

In 1945, as the Allies began to reclaim territory across Europe, they also began confiscating German intelligence and technology for themselves. Then, in March of that year, a Polish lab technician discovered pieces of the Osenberg List hastily stuffed into a Bonn University toilet and delivered it to U.S. intelligence.

Establishing Operation Paperclip

At first, the United States was concerned merely with capturing and interrogating the scientists identified on the Osenberg List in a mission called Operation Overcast. But as the United States discovered the extent of Nazi technology, this plan rapidly changed.

Instead, the States would collect and recruit these men as well as their families to continue their research for the American government.

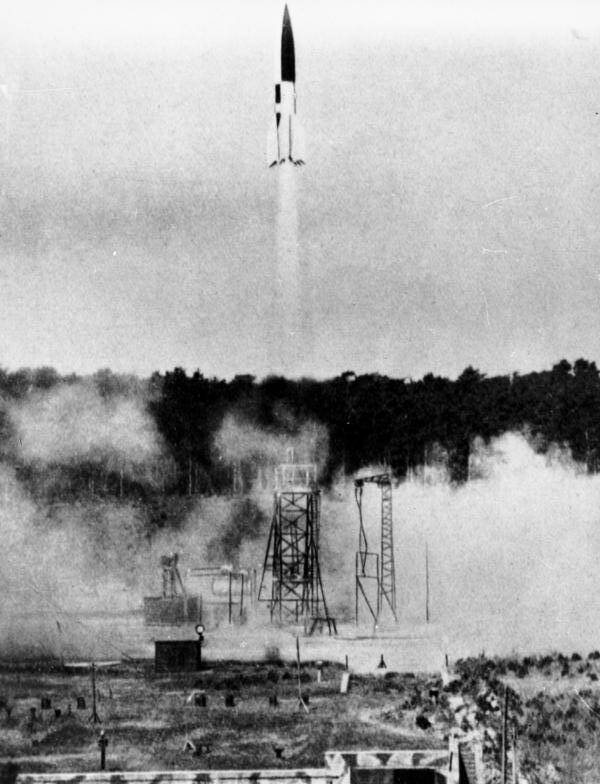

And so, on May 22, 1945, Allied troops invaded Peenemünde and captured the men who were hard at work there on the V-2 rocket, which was the world’s first long-range guided ballistic missile.

Wikimedia CommonsA V-2 rocket test launch at Peenemünde, Germany in 1943.

A newfound Joint Intelligence Objectives Agency (JIOA) and the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), which was eventually rebranded as the CIA, was responsible for putting the program now officially called Operation Paperclip into action. However, even though President Truman had sanctioned the project, he had also ordered that the program could not recruit any documented Nazis. But when the JIOA realized that many of the men they wanted off the Osenberg List were Nazi sympathizers, they found a way to circumvent the law.

The JIOA thus chose not to vet any researchers before they were brought into the U.S. and only once they had arrived. They also whitewashed or erased incriminating evidence from their records.

The Nazi Scientists Behind The Project

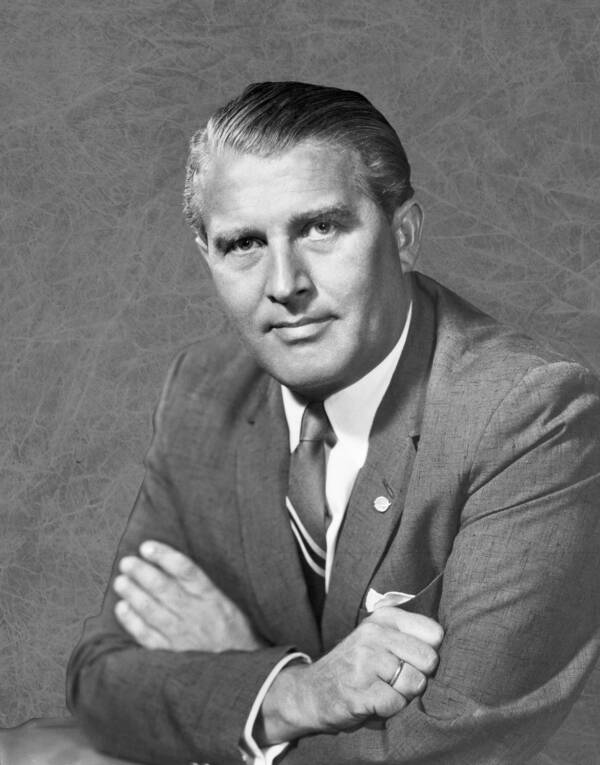

Among the scientists that were recruited under Operation Paperclip was premier German rocket scientist Wernher von Braun, who also forced prisoners of the Buchenwald concentration camp to work on his rocket program. Many of them died from overwork or starvation, yet Braun would go on to become the director of NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center.

Wikimedia CommonsWernher von Braun used Buchenwald concentration camp prisoners for slave labor.

“When they were running low of good technicians, Wernher von Braun himself traveled nearby to the Buchenwald concentration camp, where he hand-picked slaves to work for him.” added Jacobsen.

“He is a great example, because you wonder where the deal with the devil really happened in terms of his whitewashed past,” said Jacobsen. “The U.S. government, NASA in particular, was so complicit in keeping his past hidden.”

To Jacobsen’s point, Wernher von Braun was nearly awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom during the Ford administration. Only the objections of a senior advisor made Ford reconsider.

Upon arriving in the States in 1945, von Braun worked on rocketry at the U.S. Army in Fort Bliss, Texas. There, he oversaw the launching of several V-2 test flights.

Von Braun was transferred to NASA in 1960 where he helped the agency to launch its first satellites into orbit on July 20, 1969, as part of America’s effort to win the space race. By this point, he had been accepted by U.S. officials as an invaluable mind and he lived out the rest of his days in peace until dying of pancreatic cancer in 1977.

While he had certainly been the most famous of the German scientists, nearly every key department at the Marshall Space Flight Center was filled with former Nazis. Kurt Debus — a former SS member for Nazi Germany — ran the launch site now known as Kennedy Space Center.

Others, like Otto Ambros — Adolf Hitler’s favorite chemist — were tried at Nuremberg for mass murder and slavery, but given clemency in order to help America’s space exploration effort. The man was later even given a contract with the U.S. Department of Energy.

In The Wake Of Project Paperclip

Much of Operation Paperclip’s history remains unknown, but the most up-to-date and informative work on the subject is Annie Jacobsen’s 2014 book.

Throughout the latter part of the last century, journalists have attempted to uncover more about Operation Paperclip, but their requests for documentation were often met with lawsuits. When a few requests were finally honored, countless documents were missing.

Many of the German researchers whose Holocaust-related atrocities were simply expunged by the JIOA later went on to work on MK Ultra, a top-secret program backed by the CIA whose main objective was to generate a mind-control drug to use against the Russians.

Apologists for Operation Paperclip might claim that the JIOA only sought to bring over benign scientists but this is demonstrably false. In 2005, the Interagency Working Group established by Bill Clinton determined in its final report to Congress that “the notion that they [the U.S. military and the CIA] employed only a few ‘bad apples’ will not stand up to the new documentation.”

Getty ImagesNazi scientist-turned-NASA director Kurt H. Debus (right) gives French President George Pompidou (center) a tour of Kennedy Space Center in 1970.

The threat of the Cold War may have convinced certain American powers that granting clemency to Nazi scientists was acceptable, but was Operation Paperclip actually one of the biggest blemishes in American history — or a difficult decision that had to be made in the name of progress?

After learning about Operation Paperclip, read about Operation Mockingbird, the CIA’s plan to infiltrate the media. Then, learn about the Nazis’ Lebensborn program and its quest to breed a master race.