In the 1990s, hundreds of families in rural England reported that "phantom" social workers had abducted their children. As it turns out, the truth is worse than the urban legend.

Pixabay

There’s something particularly upsetting about urban legends involving children — especially when said legends involve children being abducted from their homes. One such urban legend was somewhat rooted in fact.

In the 1990s, British newspapers caught wind of a story that seemed to involve “phantom” social workers. These individuals — posing as social workers — would travel to family homes, officially to check on children. Then, they would take the children from the home for “evaluation.”

As if the urban legend of the so-called phantom social workers didn’t frighten parents enough, the very true story that journalists believe spawned the tales is a million times worse.

The Origins of “Phantom” Social Workers

The earliest versions of phantom social worker stories typically involved several individuals, usually a couple of women accompanied by a man in a supervisory role. These individuals would call on homes with young children and perform an “inspection” of the home, and examine the children for signs of sexual abuse.

The fake social workers would then remove the children from the home, never to return. The hysteria throughout the United Kingdom, and parts of the U.S. once the story made its way across the Atlantic, was understandable, given the nature of the crime.

In 1990, local law enforcement in South Yorkshire created a task force to investigate the claims, called Operation Childcare. It received over 250 reports of this abduction, but only two proved to be genuine. Of the 250 reported cases, the task force only deemed 18 worthy of further investigation.

One such incident was reported by a woman named Anne Wylie. She said that a woman posing as a health visitor showed up at her home shortly after her 20-month-old son had been hospitalized for an asthma attack.

According to Wylie, the woman didn’t have identification, which immediately tipped Wylie off that something wasn’t right. Wylie also saw a man waiting in the car that the so-called social worker had arrived in — which Wylie found peculiar as well. When Wylie asked for more information about the purpose of the woman’s visit, the woman pulled out a file that appeared to be Wylie’s son’s medical records.

Wylie managed to get the woman to leave. When she called the local health office she found out, of course, that the woman was not a social worker.

Wylie reported the incident to the police, but they never found the woman, whom Wylie had described as “in her late twenties, about five foot four, slim with light brown hair and a small mark by her right eye. She was wearing a light blue coat,” similar to coats worn by nurses.

Operation Childcare ended within four years of its inception, and task force members never made any arrests under its banner. When attempting to explain the endeavor’s lack of results, local authorities looked to the media, whom they said played a significant role in “hyping” the very small handful of cases that could have been real, and it created something of an urban legend.

The Real Problem of Social Workers

Upon closer inspection, authorities learned that, in fact, no child had ever been successfully abducted; instead, they were “examined.”

Criminologists who worked within Operation Childcare tried to develop a profile of potential suspects, and uncover possible motives, and the best they came up with was similar to child abduction cases in general: pedophiles, women who had lost children of their own, copycats, and self-appointed vigilantes who thought it was their task to save children from abuse — real or imagined.

It was the latter group that may have spurred the development of such an urban legend. In the previous decade, a major child abuse scandal had rocked the United Kingdom. At the center of which were two physicians who abused their power in unfathomable ways.

Spotlight On Abuse

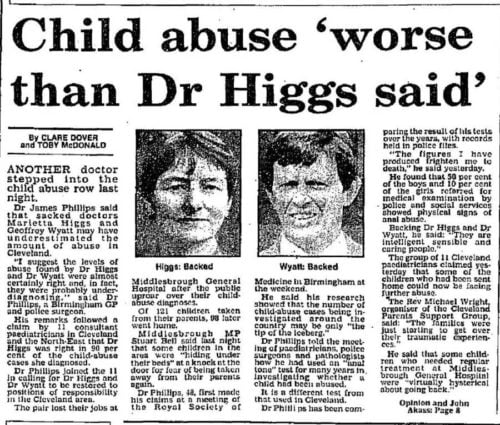

In the 1980s, a duo of doctors named Marietta Higgs and Geoffrey Wyatt devised what they believed was a highly necessary, if not wildly controversial, diagnostic test for detecting sexual abuse in children.

As pediatricians, it was certainly within the scope of their work to be vigilant in recognizing possible signs of abuse in the children they treated. The problem was the procedure they developed — one which went far beyond anything parents, social workers, and the medical profession had ever seen, and one which traumatized far more children than it saved.

Higgs believed that by using “relax anal dilation” — also called RAD — she could irrefutably diagnose sexual abuse in children. The procedure involved examining and at times probing the area around a child’s anus. Based on the area’s physiological response, Higgs believed she could determine if the child had experienced sexual abuse.

Other pediatricians used the procedure as well, but Higgs and Wyatt really put it on the map. After all, they used it in order to justify removing more than one hundred children from their homes in just a few months.

Not only was Higgs and Wyatt’s procedure damaging, many experts doubted its authority in determining if a child had in fact been abused. Other pediatricians noted that the so-called positive responses that Higgs believed to indicate sexual abuse could also turn up in children who had not been abused.

Pediatricians’ criticisms didn’t seem to matter much, at least initially. Higgs and Wyatt used their method to refer dozens of children to a Middlesborough hospital for evaluation and treatment for sexual abuse (at one point, 24 children were at the hospital in a single day).

Still, the number of children removed from their homes prompted a public investigation into Higgs and Wyatt’s methodology. A woman named Elizabeth Butler-Sloss led the public inquiry, and concluded that the majority of Higgs and Wyatt’s diagnoses were incorrect.

As a result, 94 of the 121 children whom they had removed returned to their homes.

The inquiry also offered up new legislation: In 1991, four years after the investigation began, legislators implemented the Children Act. It mandated that social workers should intervene at an absolute minimum and that even if a social worker removes a child from home, the social worker must make reunification with the family (either parents or extended family) an immediate priority.

Most important of all, the Children Act mandated that the social worker take the wishes of the child into account. This gave a voice to foster youth, one which public employees often ignored as they believed they always knew what was in the child’s best interest.

Decades after Higgs and the hysteria of “phantom social workers,” dozens of now grown-up children still seek answers.

More than 60 families formed an action group called Mothers In Action, who share their stories of separation at the hands of social workers — some real, some imagined.

Next, learn about the sad origins of the phrase “Don’t take candy from strangers.” Then, read about the Spanish criminal ring that stole hundreds of thousands of babies. Finally, read up on Queen Mary I, better known as Bloody Mary.