Called "the phone of the wind," this device allows Japanese mourners to leave messages for those who died in the 2011 earthquake.

Wikimedia CommonsThe Ōtsuchi Wind Phone in 2018, before the installation of a new aluminum phone booth.

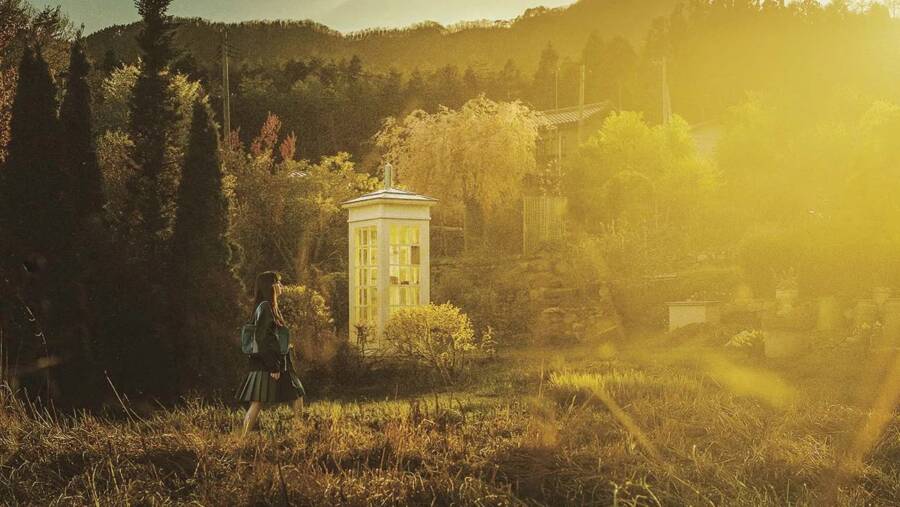

Perched on a hill in Ōtsuchi, Iwate Prefecture, Japan, there sits a quaint telephone booth overlooking the sea. Inside, there is a black rotary phone, disconnected from any network. It is known as Kaze no Denwa, or the “Wind Phone,” a sanctuary where visitors can “call” their lost loved ones to share words left unsaid or seek a connection beyond the physical realm.

The first wind phone was installed by a man named Itaru Sasaki, a garden designer who lost his cousin to cancer in 2010. The disconnected phone booth in his garden became his personal coping mechanism, believing that by speaking into the wind, his thoughts could reach his departed cousin.

But one year later, a national tragedy compelled Sasaki to open the “Phone of the Wind” to the public, offering a space for others to grieve their losses in the aftermath of the catastrophic 2011 earthquake and tsunami that claimed the lives of more than 19,000 people in the Tōhoku region.

Since then, Sasaki’s wind phone has been visited by more than 30,000 people, and his is not the only one. According to a map from My Wind Phone, similar booths have been installed across the world, with 265 in the United States alone and another 111 worldwide.

Clearly, something about Sasaki’s philosophy has resonated across cultures — perhaps a testament to the universality of grief and the search for meaning that follows.

Itaru Sasaki’s Phone Of The Wind In His Home Garden

Ōtsuchi, in Japan’s Iwate Prefecture, is a small fishing village on the east coast. In 2010, it had a population of 16,000 people, a fairly close-knit community that had once shared a collective reverence for the ocean goddess Benzaiten, who was said to grant fishermen bountiful catches and safety on the seas. Many of the island’s older population had maintained this admiration, even if the youth had lost their faith.

Itaru Sasaki was a resident of Ōtsuchi, a garden designer who had a close relationship with a cousin who also lived on the island. His cousin, a calligrapher and martial arts instructor, told Sasaki in 2010 that he had been diagnosed with stage four cancer and had just three months to live.

When his cousin passed, Sasaki began installing a phone booth in his garden as a way to “speak into the wind,” as it were, and carry his thoughts to his cousin in the afterlife.

Wikimedia CommonsThe wind phone in Itaru Sasaki’s garden, a private place which he has opened to the public to express their grief.

“Life is only, at most, 100 years,” Sasaki said, speaking with The Believer’s Tessa Fontaine. “But death is something that goes on much longer, both for the person who has died and also for the survivors, who must find a way to feel connected to the dead. Death does not end life. All the people who are left afterward are still figuring out what to do about it.”

Sasaki and his wife lived on the top of a hill overlooking the rest of Ōtsuchi, where most residents had established homes and businesses along the ocean. When Sasaki finished his wind phone in December 2010, Ōtsuchi looked the same as it always had.

Three months later, it was all but gone.

The Unprecedented Destruction Of The 2011 Tōhoku Tsunami

Wikimedia CommonsŌtsuchi in the wake of the 2011 tsunami that devastated the coast of Japan.

On March 11, 2011, a magnitude 9.1 earthquake tore across the seafloor near Japan, sending waves reaching 128 feet in height hurtling toward the Japanese coast. The waves crashed into the city of Miyako first, while water inland in Sendai spread across six miles.

217 square miles of Tōhoku were flooded with water. Hospitals, schools, businesses, homes, railways, and nearly everything else in the water’s path was destroyed. The devastating torrent also caused a cooling system failure at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, leading to an infamous meltdown that displaced more than 150,000 people.

Wikimedia Commons12-story-high waves barreling into the city of Miyako on March 11, 2001.

The tsunami itself, meanwhile, claimed the lives of more than 19,000 people. Millions more lost access to running water and electricity, and more than 120,000 buildings were destroyed in just a few minutes. Japan’s Reconstruction Agency estimated the total financial damage to be around $199 billion — The World Bank put it higher, at $235 billion.

Those who survived were forever changed. Their homes had been destroyed, their livelihoods taken from them, and, in many cases, their loved ones too. Official figures released in 2021 reported 19,759 deaths, 6,242 injured, and 2,553 still missing.

TohoThe 2022 film Suzume by director Makoto Shinkai centers around the grief that stemmed from the 2011 tsunami.

Grief manifested in strange ways for many people, as it always does. Months later, many reported seeing the spirits of Tsunami victims across the Japanese coast, a phenomenon closely related to yōkai, the not-quite-spirits of Japanese folklore. For others, though, grief left them lost and searching for meaning.

So, Itaru Sasaki opened his garden to them.

The Wind Phone Became A Site Of Pilgrimage For The Bereaved

Broadmedia StudiosA scene from the film Voices in the Wind, which features the wind phone.

“It all happened in an instant, I can’t forget it even now. I sent you a message telling you where I was, but you didn’t check it,” Kazuyoshi Sasaki said, speaking to his wife Miwako through the wind phone, in an account shared by Reuters.

“When I came back to the house and looked up at the sky, there were thousands of stars, it was like looking at a jewel box. I cried and cried and knew then that so many people must have died.”

Kazuyoshi Sasaki had spent days searching for his wife, sifting through the rubble of their home, visiting makeshift morgues and evacuation centers. He never found her. Like many others, the suddenness of the tsunami and the devastation it brought meant he never got to say goodbye. There were many things left unsaid.

“It’s not like anything else,” Itaru Sasaki explained. “It isn’t therapy. It isn’t the same as the thing you say to your friend over your second glass of wine about wishing you could talk to your dead mother about something… You pick up the phone and your brain has readied your mouth to speak. It’s wired. We do it all the time. You don’t think what it is you want to say, you just say it. Out loud.”

Wikimedia CommonsThe interior of a wind phone in Amsterdam.

Those who lost loved ones in the tsunami weren’t the only ones who found the wind phone cathartic. More than 30,000 people have visited the phone at Sasaki’s garden, but now there are more than 300 other wind phones scattered about the globe, each with the purpose of providing a space for people to connect with those they have lost.

“While perhaps existing only in our hearts and minds, the symbolic phone conversation creates a palpable link to those we have lost and allows us to speak the unspoken, to utter what we wish we would have said before they died, to whisper goodbye, to say I love you one more time, to right a wrong,” Professor Donnelle Dreese wrote for Psychology Today in 2024.

For many, the COVID-19 pandemic created a similar need as those who had lost loved ones in the 2011 tsunami. Lives were tragically and suddenly cut short; many around the globe were robbed of a last goodbye. That collective grief led organizers to reach out to Sasaki to set up wind phones in Europe and the United States.

“There are many people who were not able to say goodbye,” Sasaki said. “There are families who wish they could have said something at the end, had they known they wouldn’t get to speak again… Just like a disaster, the pandemic came suddenly and when a death is sudden, the grief a family experiences is also much larger.”

After learning about how the wind phone has helped people deal with grief, learn about the fascinating way in which the Toraja people of Indonesia honor their dead. Or, read about the town of Nagoro, Japan, where the dead are replaced with life-sized dolls.