Even before America became a sovereign nation, a freed slave named Prince Hall fought for the emancipation of his people in Boston and beyond.

Throughout the 1770s, Prince Hall fought tirelessly for the rights of Black people in America.

Known today as a “Black founding father” alongside other early American patriots of color like double-agent James Armistead Lafayette, Hall joined the Revolutionary War as a free Black man and called for abolition decades before Abraham Lincoln issued his Emancipation Proclamation.

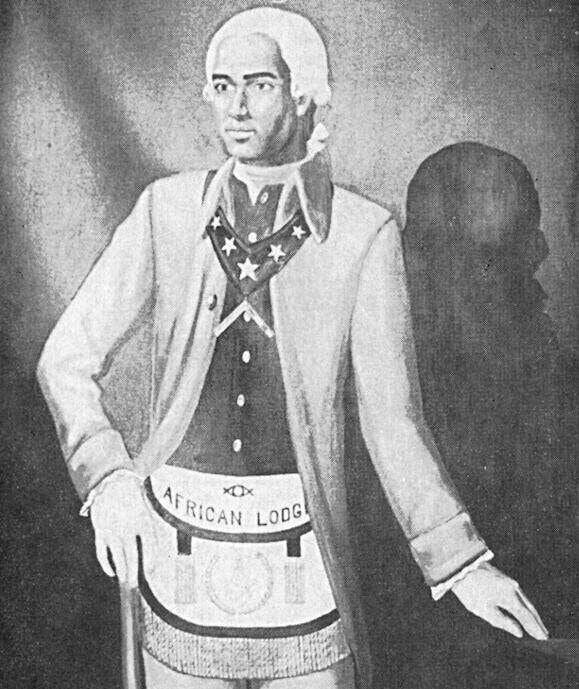

Wikimedia CommonsThe only known portrait of Prince Hall, painted after his death.

Although he faced a state legislature that rejected most of his petitions, Hall continued to fight and encouraged free Black people to follow in his steps. “My brethren,” Hall declared, “let us not be cast down under these and many other abuses we at present labour under: for the darkest is before the break of day.”

Together with other revolutionaries of color, Hall established the African Lodge No. 1, which was the first society in American history devoted to socioeconomic improvement.

Prince Hall Joins The Revolution

Wikimedia CommonsBlack and white soldiers fought side-by-side for the colonies during the Revolutionary War.

Born a slave in Boston around 1735 — though some sources claim he was born in Barbados or the West Indies — Prince Hall was owned by a leather craftsman named William Hall. After decades in bondage, Hall finally earned his freedom on April 9, 1770.

His emancipation document stated that he was “no longer Reckoned a slave, but [had] been always accounted as a free man.”

His freedom came only one month after the Boston Massacre, a riot between American revolutionaries and British soldiers. With the Revolutionary War brewing, Hall opened his own leather workshop in Boston and registered as a voter and taxpayer. He also supported the Revolution by making leather products for Boston regiments.

Like many other Bostonians, Prince Hall supported the American Revolution and the break from Great Britain. When the war broke out, Prince Hall saw an opportunity for Black people. He believed that if he and other Black people joined up with the revolutionary army, then they could cement their place as freedmen in the new nation of America.

As one of the city’s most prominent free Black men, Hall encouraged Boston’s free Black communities to sign up with the Revolutionary Army.

Hall’s own son enlisted in the war, and Hall himself may have fought too as six Black men named “Prince Hall” were listed on Massachusetts regiments.

Petitioning For Abolition

Wikimedia CommonsThe Old State House in Boston where the state’s legislature met when Prince Hall petitioned them.

In 1777, Hall petitioned the Massachusetts legislature to emancipate the state’s enslaved people. In his petition, Hall drew on the newly-written Declaration of Independence and used its language of inalienable rights to tear down the institution of slavery.

Hall wrote on behalf of slaves who “have in Common with all other men a Natural and Inalienable Right to that freedom which the Great Parent of the Universe hath Bestowed equally on all mankind.”

He condemned slavery as a “violation of laws of nature,” drawing on the same Enlightenment language used by Thomas Jefferson when he wrote the Declaration of Independence.

The petition, which came only six months after the colonies declared their independence from Britain, made Prince Hall the first American to use the Declaration of Independence to argue not for war but for civil rights.

Hall’s advocacy did not receive an immediate response. But in 1783, his hard work paid off when Massachusetts outlawed slavery based on the state’s constitution, which was written by John Adams, and declared that “men are born free and equal.”

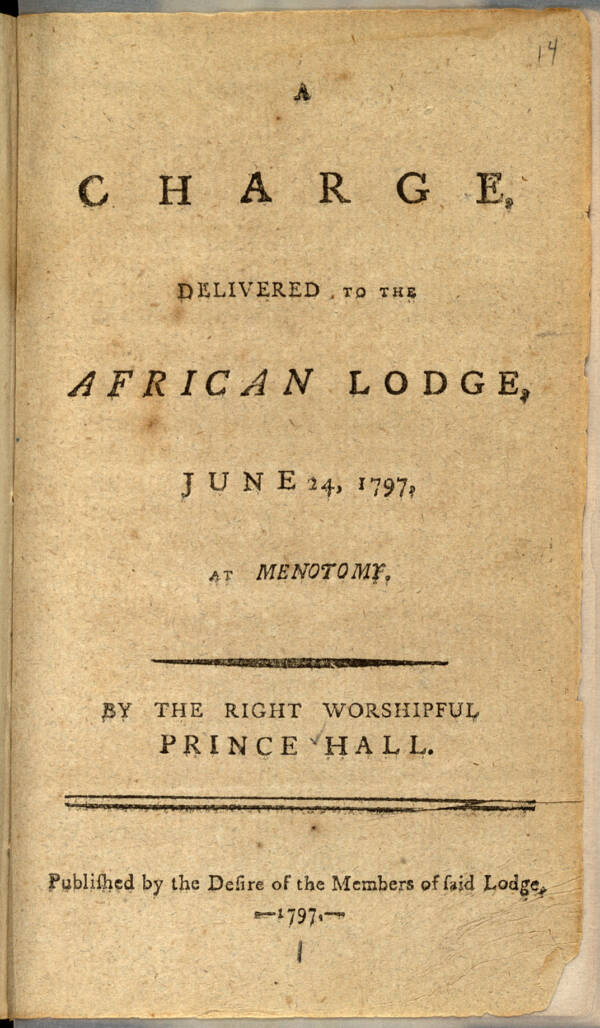

Prince Hall/Library of CongressPrince Hall published pamphlets to spread his message, including one in 1797 that carried his remarks on mob violence against Black Bostonians.

This wasn’t Prince Hall’s first effort to improve conditions for Black Americans, however. In 1773, he petitioned the legislature for a new law allowing Black slaves to work for themselves one day each week to raise enough money to buy their freedom.

When his 1777 petition failed, Hall returned in 1788 to lobby for the end to the slave trade after slavers kidnapped three free Black men in Boston. That petition succeeded, and that same year, Massachusetts passed laws to prevent the trade of slaves in their state.

The Making Of The Prince Hall Freemasonry

John Singleton Copley/Smithsonian InstitutionA 1777 portrait by John Singleton Copley of a Prince Hall contemporary.

In addition to lobbying the early American government, Prince Hall also devoted himself to Freemasonry, a collection of fraternal societies that didn’t historically accept Black men.

But Black Masons still experienced prejudice. In 1775, immediately before the war broke out, a British lodge invited Hall and a handful of other Black men to join. After they signed up, the lodge withdrew from Boston during the war. In response, Prince Hall and 24 other men of color founded African Lodge No. 1, the first group of Black Freemasons.

But the American order of Masons denied Hall’s lodge a charter. So, in 1784, Hall reached out to the British for recognition. He petitioned the Grand Lodge of England and told them how although he had fought for the colonies, they still refused to acknowledge his all-Black lodge.

In 1787, Prince Hall finally became the Grand Master of his own lodge and chartered new Black lodges as well. Today, Hall is recognized as the founder of Black Freemasonry, and his movement terms itself Prince Hall Freemasonry.

Remembering The Forgotten ‘Black Founding Father’

Despite all his efforts to create a more equitable nation, Prince Hall was still often ignored by his government.

When Shay’s Rebellion, an armed uprising in opposition to the Massachusetts state legislature raising taxes, broke out in 1786, Hall offered to raise a militia of 700 Black men to quell it. But the governor turned him down.

Although Hall had led the fight for Black rights, he found himself struggling for recognition. The following year, he petitioned for state funding to help free Blacks move to Africa.

He also petitioned for Black public schools. Hall argued that because free Blacks paid taxes that funded public education, though only for white students, Black children should also be allowed to enroll in those schools.

When the legislature denied his petition, Hall founded his own institution for children: the African Free School.

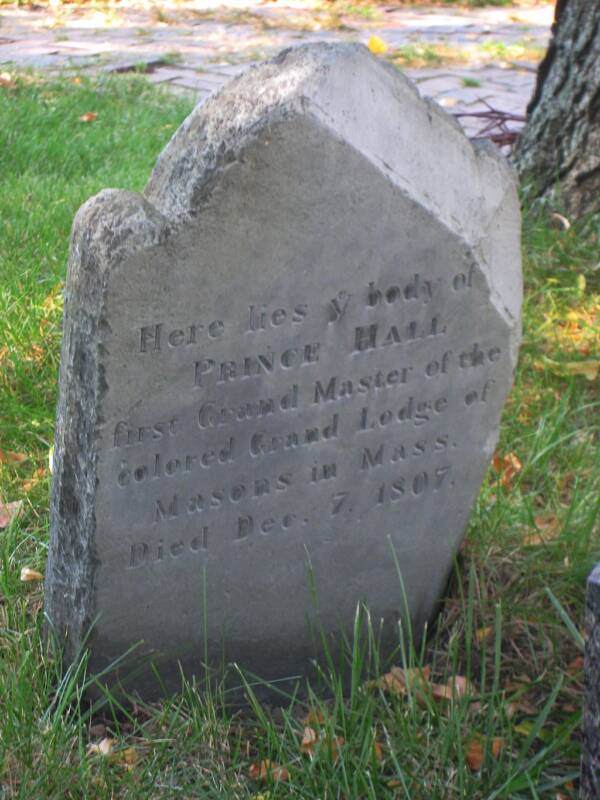

Daderot/Wikimedia CommonsPrince Hall was buried in Copp’s Hill Burying Ground in Boston.

At every step, Prince Hall faced resistance from white Americans. Yet, he continued to fight for the rights of his people until he died. As he declared in 1797, “Patience, I say; for were we not possessed of a great measure of it, we could not bear up under the daily insults we meet with in the streets of Boston, much more on public days of recreation.”

In his last speech, Hall praised the courage of Black Americans. “How, at such times, are we shamefully abused, and that to such a degree, that we may truly be said to carry our lives in our hands, and the arrows of death are flying about our heads… ’tis not for want of courage in you, for they know that they dare not face you man for man.”

Prince Hall died at the age of 72 in 1807. African Lodge No. 1 changed its name that year to Prince Hall Grand Lodge.

After reading about how Prince Hall and the founding of the Prince Hall Freemasonry, learn about William Still, the father of the Underground Railroad. Then, read about the Black intersectional feminist Mary Church Terrell.