After the release of the short film Submission, which criticized the treatment of women in Islam, Theo van Gogh attracted the ire of Mohammed Bouyeri — who took deadly revenge on November 2, 2004.

Wikimedia Commons Theo van Gogh, pictured in 1984.

The great-grandnephew of painter Vincent van Gogh, Theo van Gogh made a name for himself in the Netherlands as a provocative filmmaker. Although Theo didn’t cut off an ear and then portray the injury in art, he did have a penchant for insulting people in the name of free speech.

Unfortunately for Theo van Gogh, his actions would eventually lead to his untimely — and brutal — death at the age of just 47.

On Nov. 2, 2004, a Moroccan Dutchman named Mohammed Bouyeri shot van Gogh twice before slitting his throat in Amsterdam. Horrified witnesses later said that van Gogh’s throat was “cut like a tire.” The provocateur’s voice was symbolically and violently silenced with the flash of an assassin’s knife.

Before leaving the scene, the 26-year-old Bouyeri pinned a letter to van Gogh’s body with a knife. The letter said that Bouyeri’s gripes were actually with Ayaan Hirsi Ali, a Somali refugee turned Dutch politician. Hirsi Ali had famously worked alongside van Gogh on a short television film called Submission, which criticized the treatment of women in Islam.

Since Hirsi Ali was under police protection at the time, Bouyeri couldn’t kill her. But sadly for van Gogh, he was still an open target.

The Controversies Leading Up To Theo Van Gogh’s Shocking Murder

Theo van Gogh, born on July 23, 1957, in The Hague in the Netherlands, had already made a name for himself as a provocateur by the time he decided to release the film Submission. He had publicly criticized Islam as well as Christianity and Judaism, and portrayed himself as a “village idiot” who was able to get away with saying things others could not.

He believed that his status and his passionate defense of free speech would be enough to protect him from harm and danger, at one point even saying, “No one kills the village idiot.”

But in September 2004, when van Gogh and Hirsi Ali released a 10-minute, made-for-TV film on women in Islam, van Gogh was wholly unprepared for the backlash that would come. The film, titled Submission, Part I, focused on women praying to Allah to free them from their horrible lives, which included physical and sexual abuse at the hands of men.

Controversially, the film also featured verses of the Quran written on the bodies of naked women, in protest of the abuse they had suffered.

According to van Gogh’s interpretation of the Quran, a truly Islamic marriage required women to be fully submissive to their husbands, giving the men the right to essentially enslave their wives for all intents and purposes.

Wikimedia Commons Theo van Gogh, pictured in his later years.

The film was also partly inspired by Hirsi Ali’s own life before she arrived in the Netherlands. She fled Somalia after realizing she wanted to escape an arranged marriage, and also left her Muslim faith behind.

By the time she had written the script for the film, Hirsi Ali had become a member of the Dutch Parliament. Van Gogh, who had a lot to say about Islam, seemed like the obvious choice to direct the movie.

As expected, Submission, Part I was not well received in the conservative Muslim community at the time of its release. Some other critics argued that the film fed into larger anti-Muslim sentiment that had emerged following the 9/11 terrorist attacks in the United States.

When asked why he made the film, van Gogh said that he “intended to provoke discussion on the position of enslaved Muslim women.” He also insisted, “It’s directed at the fanatics, the fundamentalists.”

The fundamentalists heard van Gogh loud and clear.

The Aftermath Of Theo Van Gogh’s Sudden Death

Unbeknownst to Theo van Gogh, his film had attracted the attention of Mohammed Bouyeri, a man who held both Dutch and Moroccan citizenship. Though Bouyeri had been born and raised in the Netherlands in a seemingly normal and “quiet” household, he started becoming involved in radical Islam after his mother died of cancer when he was 18 years old.

The movie Submission sent Bouyeri into a rage. Though he was mostly angry with Hirsi Ali, who he viewed as a traitor, Hirsi Ali was under heavy police protection following death threats she received for the film and other public criticisms she made against Islam. Ultimately, the police protection made it difficult for Bouyeri to target her directly with violence.

So he decided to target Theo van Gogh instead, since he had refused police protection, even though he had received death threats as well.

Shortly after van Gogh’s brutal murder on Nov. 2, 2004, Bouyeri was arrested. He not only admitted to killing van Gogh, but also vowed to kill again if the police released him, claiming that the murder was him defending the name of Allah. By 2005, he had been sentenced to life in prison.

Meanwhile, Hirsi Ali responded to her colleague’s sudden demise: “I am sad because Holland has lost its innocence. Theo’s naiveté wasn’t that [murder] couldn’t happen here, but that it couldn’t happen to him. He said: ‘I am the village idiot, they won’t hurt me.'” Hirsi Ali also lamented that van Gogh hadn’t wanted any police protection leading up to his death, recalling, “He often insisted on the need to preserve our freedom of speech. He said he would only report the threats to the police.”

Both van Gogh’s admirers and critics were stunned by the loss, and it wouldn’t be long before his death changed the Netherlands forever.

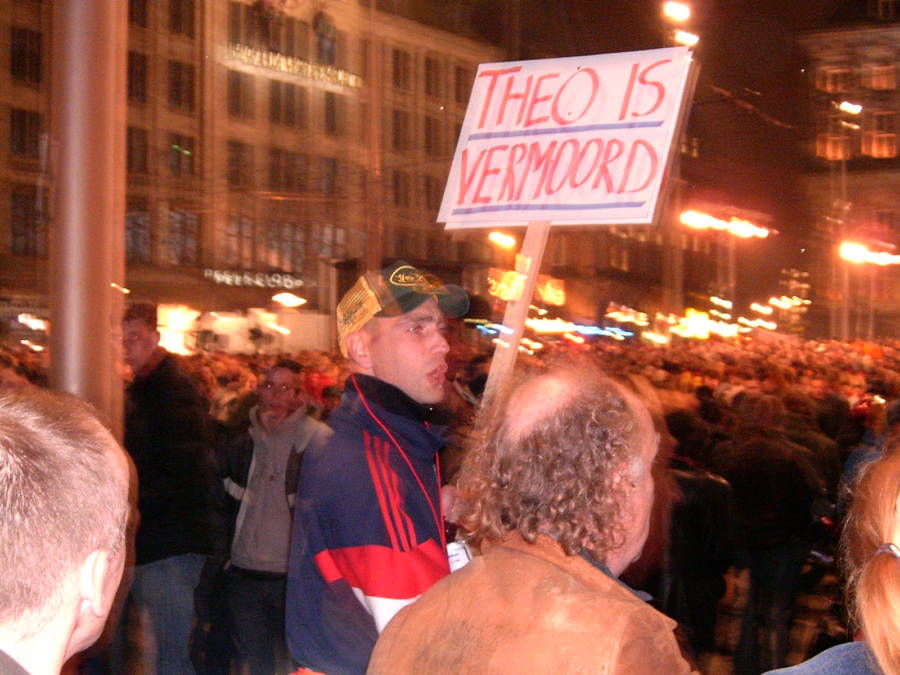

Wikimedia Commons A demonstration in Amsterdam following Theo van Gogh’s death in 2004.

Though the Netherlands has a long history of liberalism — and still carries that reputation today — van Gogh’s murder brought to light a different kind of discussion that was happening in the country.

Some politicians started talking about limiting immigration, rather than focusing on the long-held tolerance of different types of cultures. One politician claimed that Muslims, who made up just five percent of the Netherlands’ population in 2004, showed a higher percentage of criminal behavior when compared to other groups of people. All the while, some politicians began to receive more death threats than they had before.

Sadly, some innocent Muslim men in the country also started to be viewed as suspects, even if they had never been charged with a crime. One teenage boy named Samir, who was brought up Muslim in the Netherlands but no longer attended any mosque, said: “We are hated now. Whatever we do will be wrong, everything we say will be wrong, everywhere we go will be wrong.”

As the years went on, however, many prominent people in the country stopped talking about the assassination altogether, for fear of angering both right-wing and left-wing movements. Some were concerned about accidentally inciting more hatred against Muslims, while others worried that any criticism of van Gogh’s work would be seen as supporting his murderer.

Journalist Theodor Holman, who was one of van Gogh’s closest friends, has strongly criticized the silence around the murder and the fears of causing offense in the country: “Tolerance has been transformed into cowardice.”

Next, discover 11 things you didn’t know about Vincent van Gogh. Then, take a look back at the Charlie Hebdo attack that horrified France.