Despite being an amputee, Virginia Hall bolstered the Allied resistance in France so successfully that the Gestapo launched special missions just to find her. They never did.

Central Intelligence AgencyAlthough Virginia Hall became infamous among Nazi counterintelligence operatives, she was practically forgotten for much of the 20th century.

To the Nazis, Virginia Hall was “the most dangerous of all Allied spies,” and they sent their entire stable of double agents to “find and destroy her.” Her face, or one of many of her faces, was plastered on reward posters across occupied France — but the Third Reich’s most elusive adversary remained at large.

The Gestapo’s senior officer in charge of her case, Klaus Barbie a.k.a. “the butcher of Lyon,” was right to fear her. He never even managed to uncover her true nationality — or her real name.

This so infuriated Barbie that he once reportedly cried out in a fit of rage, “I would give anything to get my hands on that limping Canadian bitch.”

Of course, Virginia Hall wasn’t Canadian. And that wasn’t all the Nazis never knew about this daring spy.

Virginia Hall’s Unconventional Early Life

Central Intelligence AgencyHall was always more at home hunting, experimenting with new fashions, and traveling than living the staid life of an upper-class Baltimore debutante.

Born on April 6, 1906, in Baltimore, Maryland, even in her earliest years Virginia Hall was by her own admission, “cantankerous and capricious.” While Hall’s mother wanted her to marry into money and restore the family’s failing fortune, she was more at home hunting than at dances, wore men’s clothing, and once went to her upscale high school wearing live snakes as a bracelet.

Despite her eccentricities, she was an exceptional student. Hall was elected class president at Roland Park Country School, where she was also editor-in-chief of the school newspaper, captain of the field hockey team, and even “Class Prophet.” Her peers remembered her as the “most original of our class.”

Hall spent the next four years studying at Radcliffe and Barnard Colleges, but her distaste for the staid atmosphere of academics and her proficiency in French led her to travel to Paris and then Vienna.

Along the way, Hall earned a degree in economics and international law, fell in love with a young Polish army officer, and learned German, Italian, Russian, and Spanish. By the time she returned to Baltimore in 1929, she was every inch the emancipated, modern European woman.

Sexism Hinders Her Career

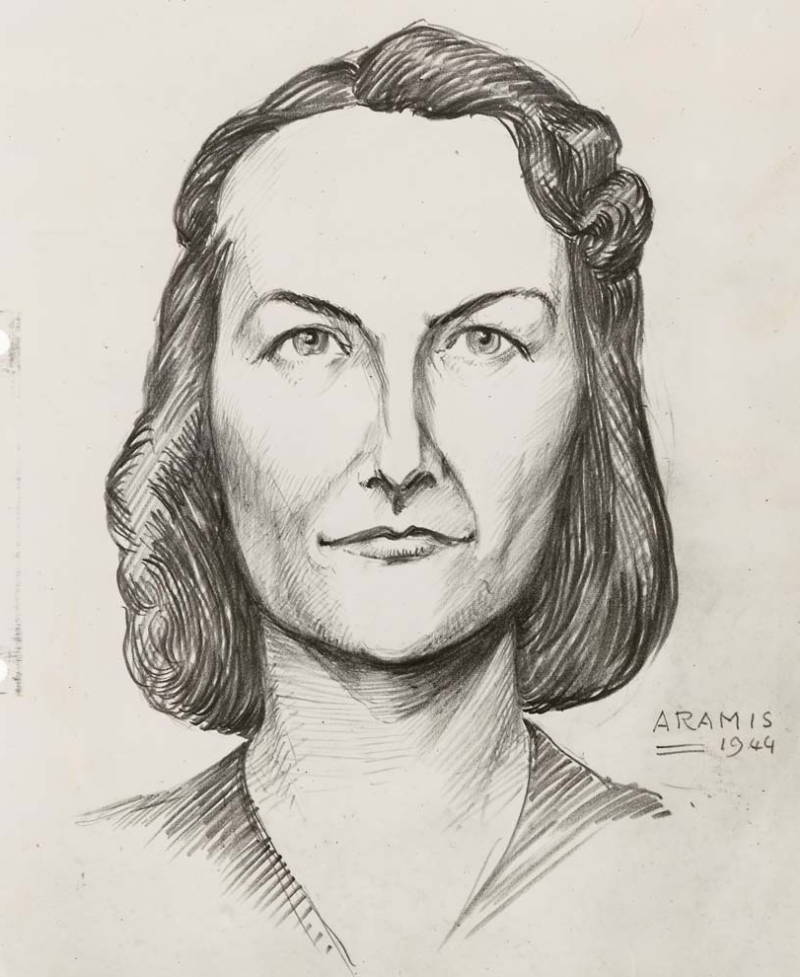

National ArchivesA sketch of Virginia Hall.

Virginia Hall’s dream was to join the State Department as a diplomat and ultimately to become an ambassador. She believed that with her proficiency in languages and her travels she was an ideal candidate for this role.

And she may well have been if Washington’s diplomatic community at the time wasn’t solidly male and its members had no tolerance for a woman in their ranks. Hall consequently sent several unsuccessful applications to join the diplomatic service, each time competing against hundreds of other women of whom only a handful would be accepted.

After her father’s death, Hall managed to secure a job as a clerk in the American embassy in Warsaw before transferring to Izmir, Turkey a few months later. It was there that, during a hunting expedition in 1932, Hall accidentally shot herself in the left foot.

The wound turned gangrenous, and only a rapid amputation saved her life, but she was left one-legged and discouraged. Equipped with a prosthetic leg that she affectionately nicknamed “Cuthbert,” Hall applied again to the diplomatic service. In 1937, she was again rejected in part due to “an obscure rule barring amputees from diplomacy.”

In response to her letter of appeal on the matter, Secretary of State Cordell Hull callously replied that Hall could become “a fine career girl” in the consular service.

Becoming An Allied Spy

Wikimedia CommonsHall used her exceptional skills of subterfuge to blend into the background and conduct her activities away from prying German eyes.

Determined to contribute to the fight against fascism, Hall resigned from the State Department and joined the French 9th Artillery Regiment as an ambulance driver in 1940.

But when the German Army crashed through the Maginot Line and swiftly overthrew the French government, she was forced to flee to London. The escape would prove to be yet another decisive moment in Virginia Hall’s life.

Hall had obtained a phone number from an acquaintance which she’d been told to call to ask for work upon reaching British soil. She assumed it would be another ambulance driving job, but was astonished to be on the phone with a senior officer of the Special Operations Executive (SOE), a top-secret British agency which Prime Minister Winston Churchill had launched in order to “set Europe ablaze.”

Through covert channels, Hall’s daring and elusiveness had so impressed the SOE that she was immediately accepted for training in weapons, sabotage, disguise, and espionage. Under the codename “Germaine,” among many others, Hall was soon sent back to France to collect intelligence on German operations there and to help organize and arm the French resistance.

Soon after reentering France in August of 1941 while posing as a reporter for the New York Post, Hall established a network of SOE operatives and French resistance fighters codenamed HECKLER.

From their base in Lyon, the heart of the resistance, HECKLER helped integrate Allied operatives into the French underground, coordinated supplies and arms, and offered logistical support to nascent resistance groups.

Fighting An Underground War In France

Wikimedia CommonsBy September 1944, 400,000 French citizens were fighting in the ranks of the French Resistance, accelerating the pace at which the Nazi occupiers were defeated.

The danger she was under was immense. Of the more than 400 SOE agents ultimately sent to France, 25 percent didn’t return, and while Hall managed to escape attention for some time, she was no match for the German Abwehr’s network of informants.

In November 1942, Abbé Robert Alesh, a French priest and informant, seemed to suspect her. This was around the time that the German occupation of France was increasing. Sensing the danger she was in, Hall took a train south to the border and walked the 50 miles into neutral Spain through the harsh Pyrenees winter.

At one point during the perilous journey, Hall was able to transmit a message to her superiors in London stating that she hoped “Cuthbert” would give her no trouble. Misunderstanding, they replied: “If Cuthbert troublesome, eliminate him.”

After a brief spell in a Spanish jail for illegally entering the country, Hall was able to get word to American officials in Barcelona who secured her release. Now considered by the SOE to be compromised, she instead joined the Office of Strategic Services, or OSS, which was the wartime precursor to the later Central Intelligence Agency.

Now codenamed “Diane,” Hall was sent to France once again but this time as the second-in-command of an older, inexperienced OSS officer. Using the cover identity of Marcelle Montagne, a rural Frenchwoman, Hall now bore a far-from-glamorous new disguise, her hair dyed gray and pulled back into a severe bun, affecting a pronounced limp, and with her teeth filed down to resemble those of a French peasant.

Throughout 1944, Hall’s men “cut sixteen railway lines, derailed eight trains, blew up four railway bridges, cut all telephone wires in the area, and killed eighty Germans while suffering just twelve casualties themselves” all under her covert command.

As a result, Hall was deemed to have made her network “a most powerful factor in the harassing of enemy troops.”

But as successful as she was, the end of Virginia Hall’s wartime career was in sight. With the Allied invasion of Normandy, operatives in the SOE and OSS were no longer as valuable, and in September 1944, Hall was finally stood down.

A Decorated Spy Returns Home

CIAVirginia Hall being awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.

After the war ended, Virginia Hall was awarded a French Croix de Guerre and an American Distinguished Service Cross, making her the only female civilian to receive one such medal during the Second World War.

She was also made an honorary Member of the Order of the British Empire. Yet as daring and as capable as she’d proven herself to be during wartime, the return of peace came with the resurrection of the barriers she’d faced so many years before.

As an analyst in the Cold War CIA, Hall was undervalued by her superiors. “No one knew what to do with her. She was a sort of embarrassment to the noncombat CIA types.”

Hall nevertheless continued to serve faithfully, performing clerical duties much like those from which she’d been so desperate to escape in the State Department a decade before.

Unsung and practically unknown, she retired from the Agency in 1966, retreating to a farm in Barnesville, Maryland with her husband, former OSS lieutenant Paul Goillot. She spent her remaining years out of the public eye, and died at the age of 76 in 1982 largely without recognition as the greatest Allied spy of World War II.

After this look at Virginia Hall, read up on another female spy, Civil War spy Belle Boyd. Then check out Inga Arvad, the suspected World War II spy romantically linked to both JFK and Hitler.