From organizing the March on Washington to working within it, Congressman John Lewis is a civil rights leader with a legendary story.

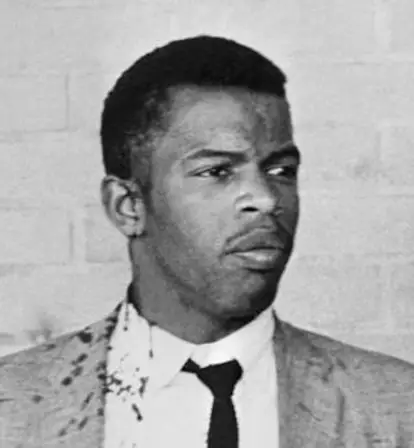

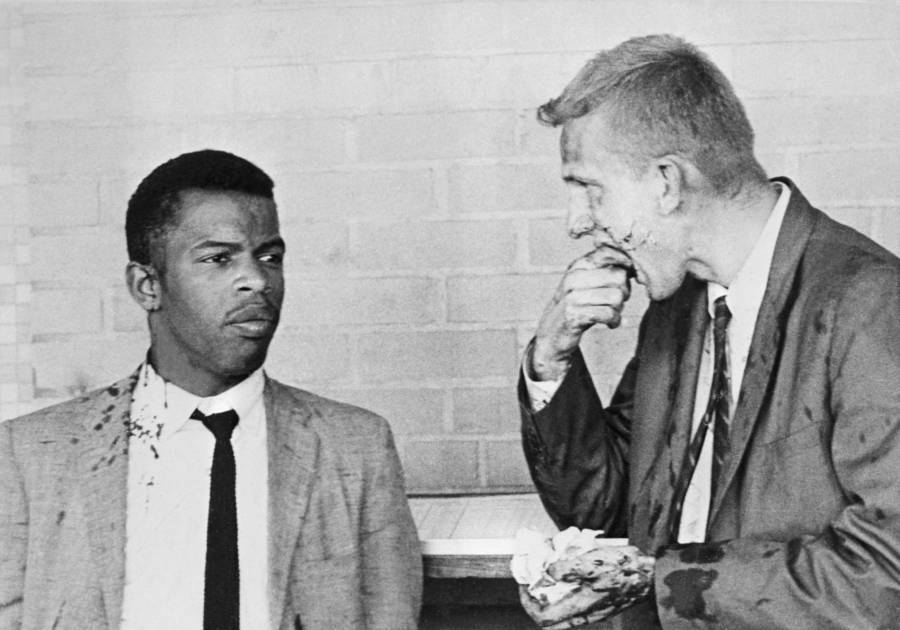

Bettmann/Getty ImagesJohn Lewis and fellow Freedom Rider James Zwerg were attacked by pro-segregationists in Montgomery, Alabama. May 20, 1961.

John Lewis has done more for civil rights in the United States than most Americans of his generation. Inspired by Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King Jr., he hasn’t stopped since 1957.

The child of sharecropper parents in segregated Alabama, Lewis rose from student activist to civil rights icon and congressman.

As the struggle against injustice wages on decades after his efforts helped legislate the Voting Rights Act of 1965, Lewis continues to help younger generations fight for reforms of their own — with unparalleled experience.

The Early Life And Activism Of John Lewis

John Robert Lewis was born on Feb. 21, 1940, outside of Troy, Alabama. Though he had a happy childhood, the racial strife comprising American life permeated his everyday experience. As the son of two sharecropper parents, he was confronted regularly by the realities of segregation and inequality.

By the time he was 6, Lewis had only seen two white people. But as he got older and visited cities up north, he became increasingly aware of how different life could be if segregation didn’t exist.

Afraid of the consequences of speaking out, Lewis’ parents urged him to stay silent regarding racial injustices. Though a natural teenage rebellion took hold, his awakening of purpose was mainly sparked by the efforts of civil rights leaders taking charge.

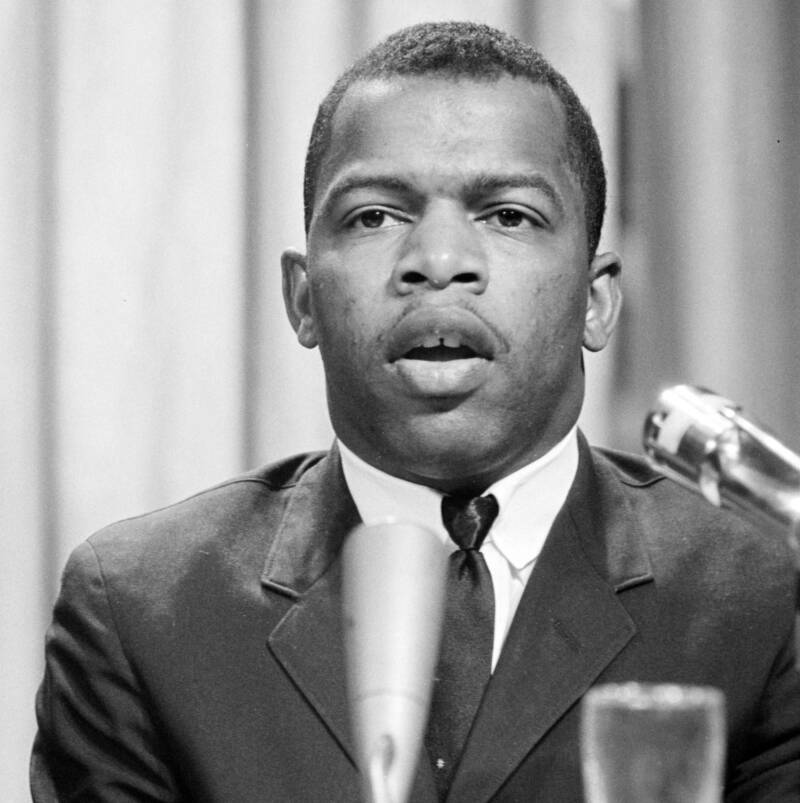

Wikimedia CommonsLewis speaking at a meeting of the American Society of Newspaper Editors. April 16, 1964.

Heartbroken by the Supreme Court’s 1954 ruling in Brown v. The Board of Education having no impact on his own school, the following years invigorated Lewis’ optimism for change.

Inspired by Rosa Parks and the Montgomery Bus Boycott and by Martin Luther King Jr. preaching of a nonviolent revolution, Lewis set course for a life of activism that has yet to veer elsewhere.

An Original Freedom Rider

Lewis left Alabama to attend the American Baptist Theological Seminary in Nashville, Tennessee in 1957. This period truly marked his foray into fighting for change, as he educated himself on the nature of nonviolent protest and worked tirelessly on organizing sit-ins at segregated lunch counters.

Wikimedia CommonsBayard Rustin, Andrew Young, Rep. William Fitts Ryan, James Farmer, and John Lewis in 1965.

Though his mother was upset about him getting arrested during these demonstrations, Lewis adamantly persisted. His efforts eventually helped lead to the desegregation of lunch counters in Nashville.

Lewis later reflected, “When I was growing up, my mother, my father, my grandparents, my great-grandparents told us when we asked about segregation, racial discrimination, ‘Don’t get in trouble. Don’t get in the way.’ But Dr. King, Rosa Parks, and so many others gave us examples like getting in the way…”

Lewis met both of these monumental figures when he was just a teenager. With a vast amount of nonviolence workshops under his belt, he focused his efforts on the desegregation of bus travel in the South. In 1961, Lewis became one of the 13 original Freedom Riders.

Paul Schutzer/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty ImagesFreedom Riders on a bus in May 1961.

Though the Freedom Rides were first conceived in 1947, the lack of confrontations and media attention failed to spur any legislative change. In 1961, student activists from the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) renewed these efforts, motivated by the success of recent sit-ins and boycotts.

Lewis joined after he and his friend Bernard Lafayette integrated their own bus ride home from college in Nashville. They refused to move to the back and sat at the front of the bus until they got to Alabama — where they noticed CORE’s announcement recruiting volunteers for a Freedom Ride.

Lafayette’s parents didn’t allow their son to participate, but Lewis joined 12 others and formed an interracial group, thoroughly trained in nonviolent conflict before the trip. On May 4, 1961, the Freedom Riders left Washington, D.C., in two buses and set course for New Orleans.

Violence first arose in Rock Hill, South Carolina, where Lewis was horribly beaten and another Freedom Rider was arrested for using a whites-only restroom.

Though the media began paying attention, the turmoil was far from over.

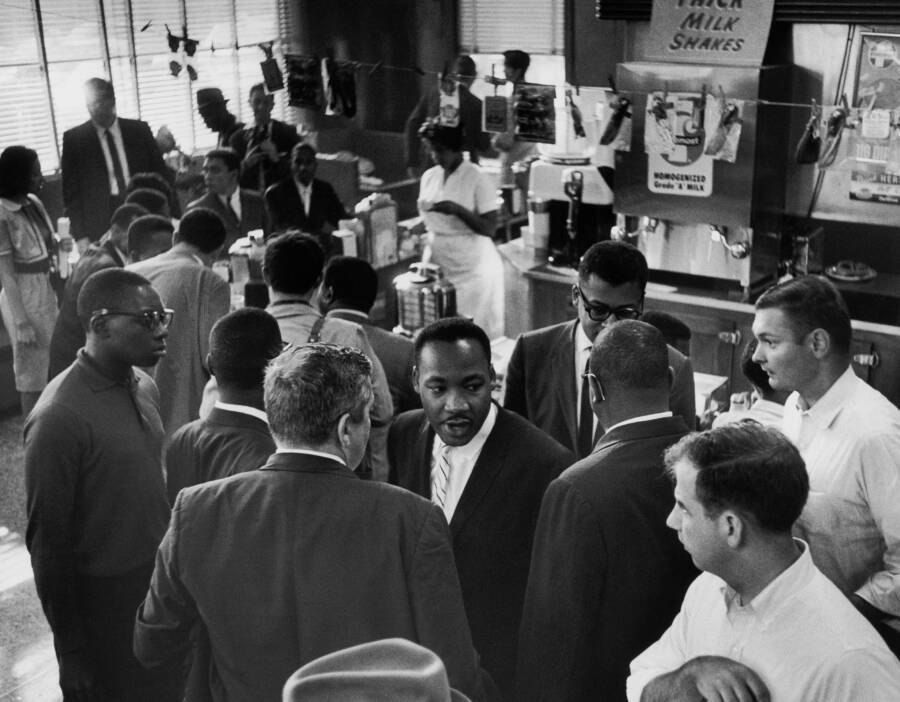

Paul Schutzer/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty ImagesDr. King meeting with Freedom Riders in 1961.

One of the buses was firebombed by the Ku Klux Klan in Alabama, forcing the fleeing passengers out into an angry white mob. At one point, Lewis was hit in the head with a wooden crate in Montgomery.

He later reflected, “It was very violent. I thought I was going to die. I was left lying at the Greyhound bus station in Montgomery unconscious.”

Finally, on May 29, 1961, the Kennedy administration directed the Interstate Commerce Commission to ban segregation in its facilities. Nonetheless, the rides continued until the ruling took effect that November.

The March On Washington

By the time Chuck McDew stepped down and Lewis took over as chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in 1963, he’d been arrested 24 times for his activist efforts.

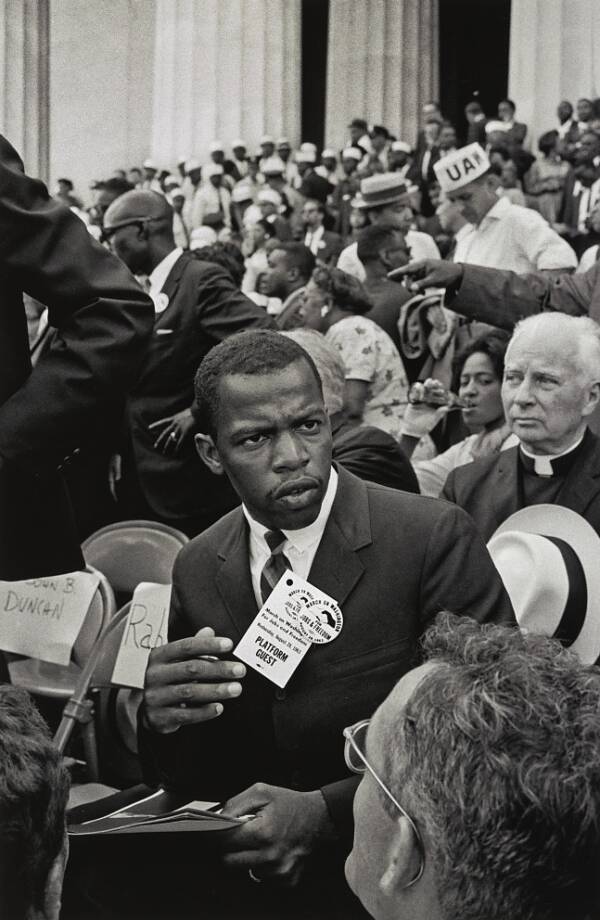

His six-year tenure saw him help organize the 1963 March on Washington. As one of the “Big Six” civil rights leaders alongside Whitney Young, A. Philip Randolph, James Farmer, Roy Wilkins, and Martin Luther King, Jr., Lewis was the youngest speaker at the historic event.

Library of CongressSNCC leader John Lewis rising to speak at the March on Washington. Aug. 28, 1963.

Though he aimed to ask whether the federal government stood with its people or with its racist policies, he was pushed to change his speech. So he decided to target the people:

“We all recognize the fact that if any radical social, political and economic changes are to take place in our society, the people, the masses, must bring them about.”

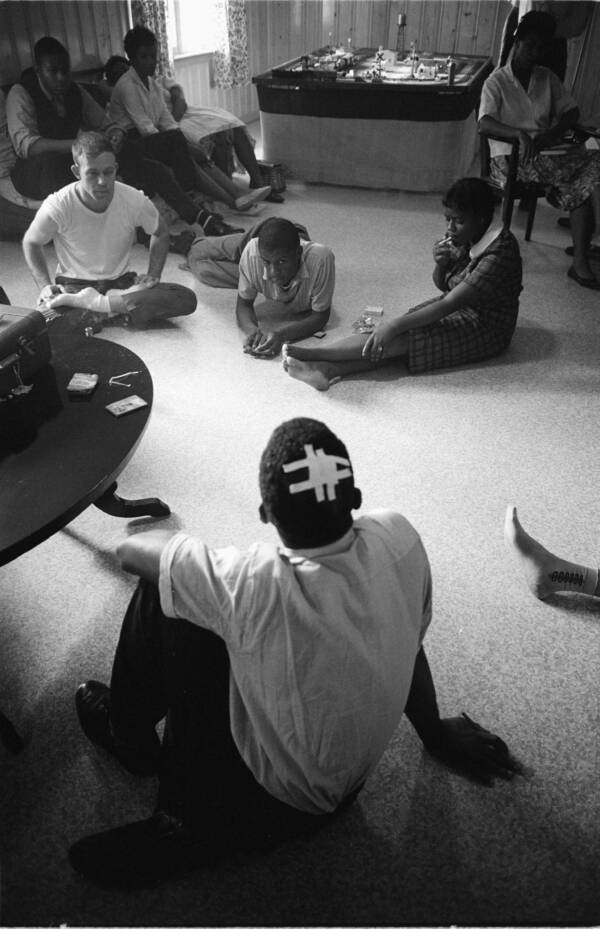

The Mississippi Freedom Summer campaign of 1964, meanwhile, focused on registering black voters and helped expose college students to the realities of being black in America.

Though the Civil Rights Act became law in 1964 as a result of all these efforts, it didn’t make it any easier for African Americans in the South to vote. While combatting this and other racist policies, Lewis and Hosea Williams organized the Selma to Montgomery March of 1965.

Paul Schutzer/The LIFE Premium Collection/Getty ImagesLewis (with the bandaged head) and fellow Freedom Riders regrouping at Brown Chapel in Selma, Alabama. March 7, 1965.

The march along the 54-mile highway from Selma, Alabama to the state capital of Montgomery came to a bloody head on March 7, 1965. Upon crossing the Edmund Pettus Bridge, some 600 demonstrators were attacked by state troopers.

Those who failed to disperse were beaten with night sticks and attacked with tear gas. Lewis himself had his skull fractured. He still bears the scars of what is now known as “Bloody Sunday” — forcing his fellow politicians and activists to look upon the wound for decades to come.

John Lewis Becomes Congressman John Lewis

The passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was undoubtedly spurred by the efforts of Lewis and fellow activists. The nation could no longer ignore the racial discrimination African Americans faced in voting. Boycotts, marches, and events like Bloody Sunday undoubtedly hastened the legislation to combat it.

Wikimedia CommonsPresident Barack Obama awarding John Lewis with the Presidential Medal of Freedom on Feb. 15, 2011.

The following year, Lewis’ tenure as SNCC chairman came to an end. Throughout the devastating assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968, he continued the national fight for equality. As director of the Voter Education Project in 1970, Lewis helped millions of voters get registered.

He won a seat on the Atlanta City Council in 1981, and was elected to the House of Representatives in 1986.

In addition to becoming one of the most respected congressmen, Lewis also helped oversee several renewals of the Voting Rights Act.

More recently, Lewis led a sit-in of around 40 House Democrats on the floor of the House of Representatives to call for gun-control measures following the 2016 mass shooting in Orlando, Florida. His urge for reform harkened back to the call for civil rights in the 1960s:

“We have been too quiet for too long. There comes a time when you have to say something, when you have to make a little noise. When you have to move your feet. And this is the time.”

A Legacy Of Liberty

From voting to privacy rights, Lewis has yet to stop fighting for equality — even in the face of severe criticism, and a dire diagnosis of cancer.

In January 2017, John Lewis said Donald Trump was not a “legitimate president,” arguing that Russian interference helped him get elected. The president then criticized Lewis’ career on Twitter, claiming the activist was “All talk, talk, talk — no action or results.”

President Trump denounced Lewis’ absence at his inauguration, reminding others he had done so before during the inauguration of George W. Bush. A spokeswoman for Lewis confirmed as much — and said it was, indeed, meant to be taken as a form of dissent.

While Lewis’ legacy of causing “good trouble” has been firmly cemented in the history books, he also helped solidify it in a series of graphic novels called March, with an upcoming documentary — John Lewis: Good Trouble — on the way.

On top of earning the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the NAACP’s Spingarn Medal, and National Book Award, Lewis is also the only person to ever win the John F. Kennedy “Profile in Courage Award” for Lifetime Achievement.

Diagnosed with Stage 4 pancreatic cancer in December 2019, he continues to support demonstrators on the streets — who are fighting for equal opportunity and the right to live without constant fear of violence.

After learning about John Lewis, find out the true story behind Elizabeth Eckford and Hazel Bryan’s iconic civil rights photo. Then, read up on Cudjo Lewis, the last living slave brought to America.