Consisting of the decades before the Civil War, the Antebellum Era was a complicated time period in American history largely defined by brutal slavery in the South.

The Antebellum Period was a time of tremendous economic growth in America thanks to the agricultural dominance in the South and the textile booms in the North. But this wealth was largely powered by the suffering of millions of enslaved African Americans who endured torture at the hands of white slaveholders, especially in the Deep South.

Strangely enough, in the decades after the Civil War, the “Antebellum South” became a whitewashed phrase used to evoke a long-lost era of sweeping plantation mansions, hoop skirts, and afternoon teas, while at the same time erasing the hideous reality of slavery in America.

Although the Antebellum Period took place before the Civil War, it certainly wasn’t the calm before the storm that some may have been taught.

What Was The Antebellum South?

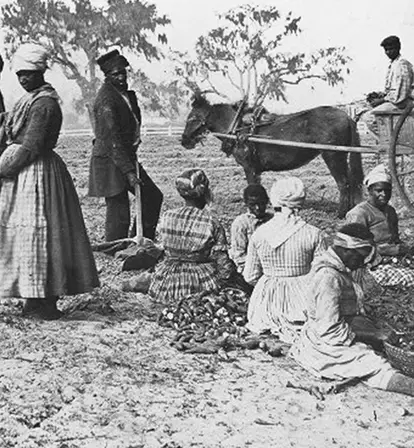

Wikimedia CommonsThe Antebellum Period was one of the most violent eras in the history of the American South.

The word “antebellum” comes from the Latin phrase “ante bellum,” which means “before war.” More often than not, it refers to the decades before the American Civil War.

There is some debate among scholars on the exact time period that the term covers. Some believe that the era began after the end of the American Revolution, while others think the Antebellum Period stretched between the War of 1812 and the beginning of the Civil War in 1861.

By all accounts, the Antebellum Era was marred by violence against millions of enslaved Black people — as well as battles that the U.S. fought against other countries.

Between 1803 and 1815, Europe was consumed by the Napoleonic Wars, which saw Napoleon Bonaparte lead France into battle against British-led forces. The conflict between France and Britain affected trade relations with America, which helped set the stage for the War of 1812.

After the U.S. declared war on Britain in June 1812, the battles lasted over 32 months. This eventually led to a British blockade of the Atlantic seaboard. Interestingly enough, these circumstances spurred domestic production within the United States — and many Americans began to thrive economically.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TRlfMhP_CMI

America’s economic growth came through the burgeoning agriculture industry in the South and the manufacturing boom in the North. Sugar cane and cotton production were especially profitable in the South, making husbandry extremely desirable to white Americans who wanted a piece of the proverbial pie.

Following the Indian Removal Act of 1830, a growing number of Southern white residents were able to purchase large plots of farmland for cheap, allowing them to become plantation owners and move up on the socioeconomic ladder.

Library of CongressA group of Black slaves in front of the Smith’s Plantation in South Carolina. Circa 1862.

Meanwhile, Black residents in the Antebellum South remained enslaved to fuel the heightened sugar and cotton production. As scholar Khalil Gibran Muhammad wrote in The 1619 Project, sugar was one of the top American commodities by the 1840s.

At one point, Louisiana planters produced a quarter of the world’s cane-sugar supply, making the state the second-richest in the country based on per capita wealth.

Though slaves in the Northern states mostly worked inside the homes as servants, the free labor of slave production also contributed to the economy of the North. It’s no wonder why this brutal system benefitted so many white Americans.

The New Power Of The U.S.

Wikimedia Commons While Europe was in turmoil during the Revolutions of 1848, the U.S. was gaining status as a new world power.

By the mid-19th century, America’s economic power had grown exponentially. At the same time, Europe was in trouble. A shortage of food supplies and heightened food prices across Europe worsened the cross-continent collapse brought on by stagnated industrialization.

The economic turmoil grew worse across Europe, most notably culminating in the Great Irish Famine in 1845. Three years later, with the public still reeling from the recession, dissent against Europe’s absolutist powers emerged across the continent.

The Revolutions of 1848 were marked by uprisings all over Europe, from Sicily to France to Sweden. Uprisings in London forced Britain’s Queen Victoria to retreat to the Isle of Wight for her own protection. Some enthusiastic Germans dubbed this period of mass uprisings as the Volkerfruhling, or the “Springtime of Peoples.”

During this time, the U.S. appeared to support revolutionary causes in various European countries, sometimes even providing financial assistance.

But the unrest in Europe also meant the U.S. — with its growing wealth from agricultural production and textile manufacturing — gained status as a new power player of the world. Moreover, Britain itself began to rely on American cotton for more than 80 percent of its industrial raw material.

Slavery In The Antebellum South

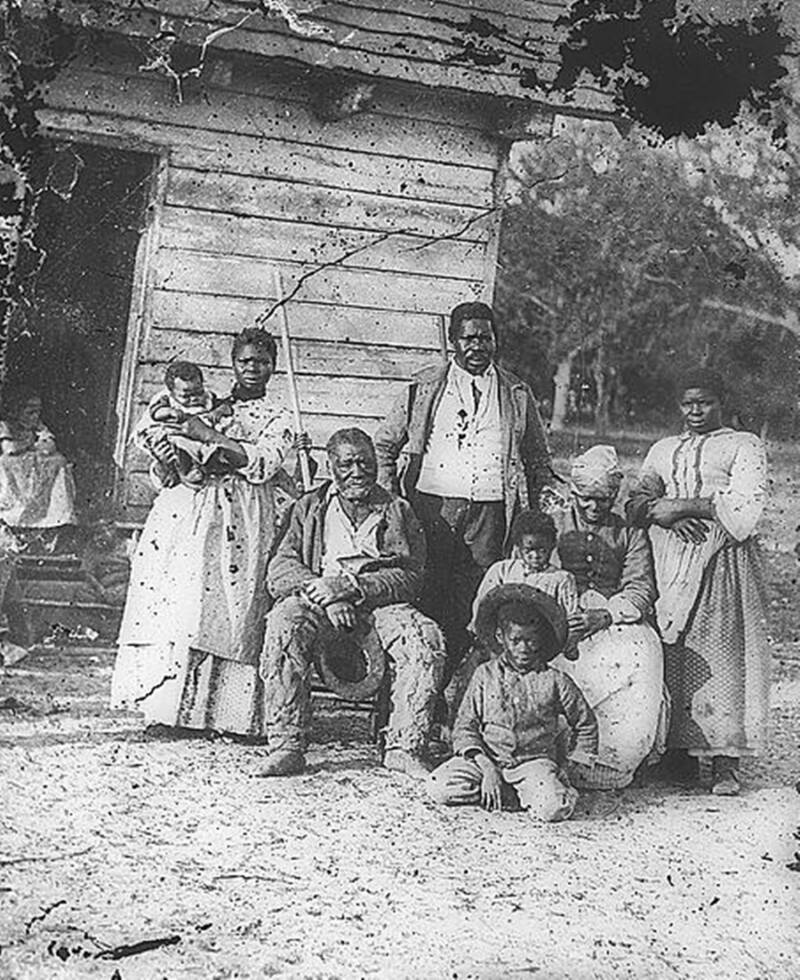

Library of CongressGenerations of Black families, like the one pictured here, were enslaved across the country.

Although slavery existed in many places in early America, the slave trade was largely concentrated in the Antebellum South due to its lucrative sugar and cotton production.

By the mid-19th century, census records showed that 3,953,760 of the 4,441,830 Black people in the U.S. were enslaved.

“On cane plantations in sugar time, there is no distinction as to the days of the week.”

Black slaves on the Southern plantations represented untold dollars that white slaveholders kept to themselves. Since they didn’t have to pay slaves for their labor, they easily reaped the high profits off of every harvest.

Beyond these economic developments was the tragic human cost of the agriculture industry in the Antebellum South. Black slaves had no rights as individuals and were lawfully treated as property by their white owners.

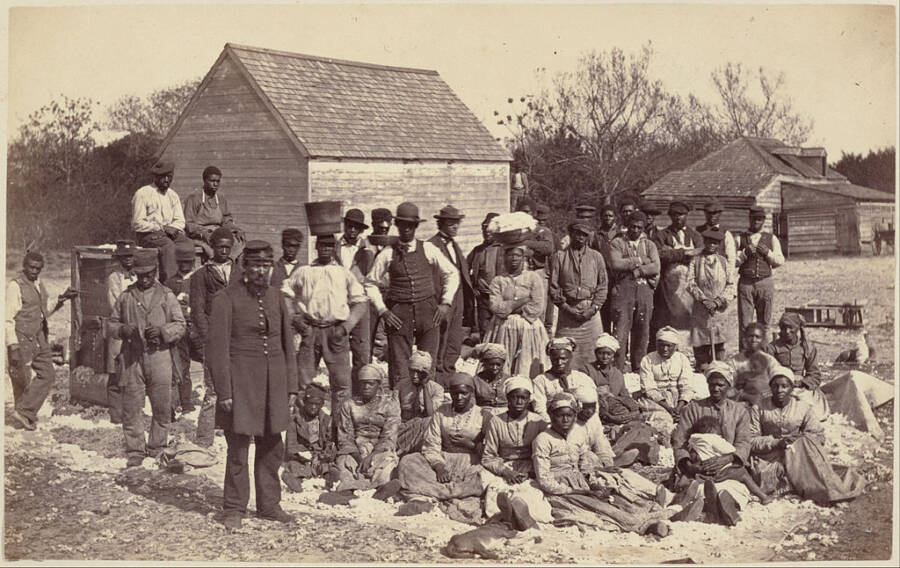

Wikimedia CommonsThe slaves of General Thomas F. Drayton, who joined the Confederate States Army during the Civil War.

Their slave status extended to their descendants, creating an inhumane cycle of chattel slavery that tortured generations of Black families. They were put to work on plantations and forced to endure grueling hours as they labored on the land, planted stalks, and harvested produce.

The unimaginable physical exertion of Black slaves was compounded by their inhumane treatment. A former slave named Louisa Adams recounted her miserable childhood on a plantation in North Carolina in a 1936 interview in the Slave Narrative Project:

“We lived in log houses daubed with mud. They called ’em the slaves houses. My old daddy partly raised his chilluns on game. He caught rabbits, coons, an’ possums. We would work all day and hunt at night. We had no holidays.”

“They did not give us any fun as I know. I could eat anything I could [get]… My brother wore his shoes out, and had none all [through] winter. His feet cracked open and bled so bad you could track him by the blood.”

Library of CongressThe “slave quarters” on the Drayton plantation in South Carolina.

Historian Michael Tadman found that Louisiana sugar parishes often showed a pattern of more deaths than births among slaves. Perhaps even more devastating, Black slaves who labored on Louisiana sugar plantations often died just seven years after they were first put to work there.

The Rise Of The Abolition Movement

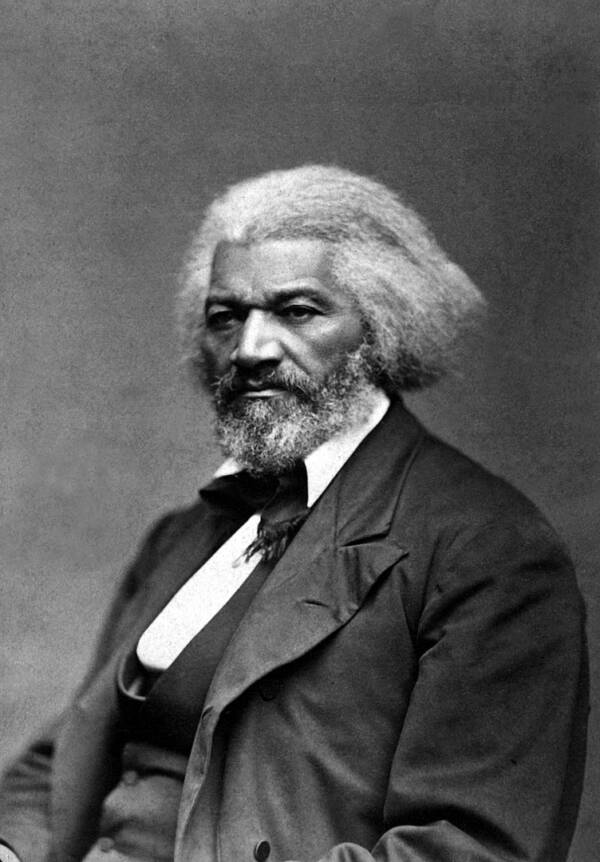

Wikimedia CommonsFrederick Douglass was a Black abolitionist who used his writings and public speeches to advocate for the abolishment of slavery.

In the 1830s, anti-slavery sentiments began to grow in some of the Northern states. Some white Americans in states like New York, Massachusetts, and Pennsylvania began to view slavery as a stain on the country’s legacy.

Moreover, the economies of the Northern states were not as directly dependent on slave labor as the Antebellum South since the North mainly prospered from manufacturing and textile industries.

“These dear children are ours — not to work up into rice, sugar and tobacco, but to watch over, regard, and protect, and to rear them up in the nurture and admonition of the gospel — to train them up in the paths of wisdom and virtue, and, as far as we can, to make them useful to the world and to themselves.”

However, it’s worth keeping in mind that the North’s profitable textile manufactures were still reliant on the raw cotton material produced by slaves in the South.

In fact, this cotton made some Northern industrialists and merchants so wealthy that they were actually supportive of slavery in the South. But while some people in New York City and Philadelphia were opposed to freeing the slaves, the abolitionist voices in the North began to get louder and louder.

The anti-slavery movement in America mobilized support through abolitionist newspapers, like The Liberator, started by white abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, and The North Star, founded by Black abolitionist Frederick Douglass.

Library of CongressDespite the growing abolitionist movement, slavery remained legal until it was officially abolished by the 13th Amendment in 1865.

Aside from abolitionists making speeches and writing articles, a growing number of slaves were taking matters into their own hands to fight against their slaveholders. Though slave rebellions had been attempted long before the Antebellum Period, many of the most well-known uprisings emerged in the early 1800s.

One of the most famous slave rebellions during the Antebellum Period was in 1831. On a plantation in Southampton County, Virginia, an uprising was led by a Black slave named Nat Turner, who organized the slaughter of 60 white people in the area. After the rebellion was quelled by authorities, Nat Turner was later executed for his role in the revolt.

But even after his execution, rebellions staged by Black slaves and free men as well as white abolitionists continued.

The Falsehood Of “Manifest Destiny” And U.S. Expansion

Aside from the issue of slavery, 19th-century America was also marked by the young country’s rapid territorial expansion. In 1803, the U.S. government purchased Louisiana from France — and nearly doubled America’s size.

Following the Louisiana Purchase, the U.S. continued expanding toward the West Coast, even though some lands there were occupied by Indigenous tribes or owned by the Mexican government. None of this stopped America from seizing new territories, even if it meant causing violence.

Many battles were fought in the name of “Manifest Destiny,” a Biblical ideology that argued that the United States had a divine right to expand its territories throughout the North American continent. Although the principles of “Manifest Destiny” had already been enacted in practice, the official term wasn’t coined until 1845 by magazine editor John L. O’Sullivan. He argued for the annexation of Texas — a former territory of Mexico — to the U.S.

Following the annexation of Texas, the U.S. wanted to claim California, New Mexico, and more land at the southern border of Texas. Mexico claimed that many of these territories belonged to them, so the U.S. offered to purchase the land. When Mexico refused to sell, the U.S. declared war on Mexico on May 13, 1846.

After American troops captured Mexico City in 1848, the Mexican government accepted the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo with the U.S. Afterward, Mexico gave up land that makes up all or parts of present-day Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming. Mexico also gave up all claims to Texas and recognized the Rio Grande as America’s southern boundary.

The Civil War And The “Lost Cause” Myth

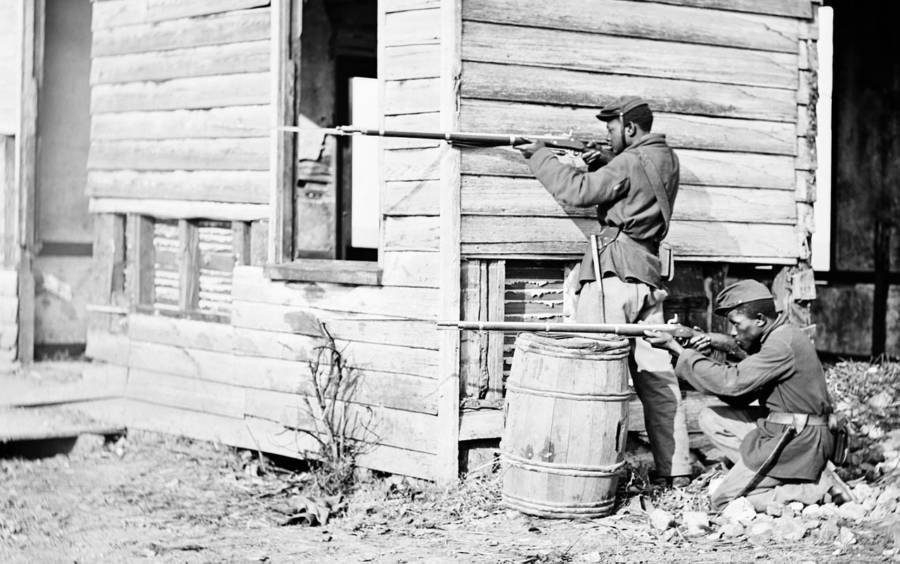

Library of CongressBlack Union troops at Dutch Gap, Virginia, in November 1864.

As Black slaves began to escape from slavery, abolitionists formed an unofficial nationwide network of white and Black advocates who helped keep former slaves safe during the perilous journey out of the Antebellum South. This was known as the Underground Railroad.

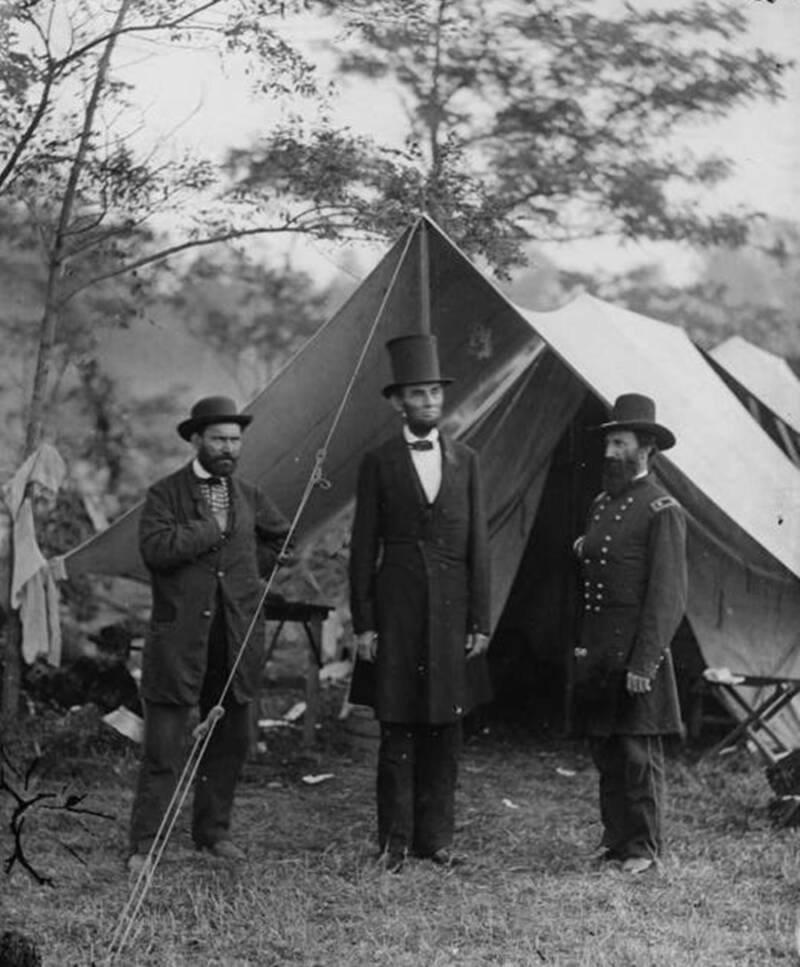

Tensions between abolitionists and slaveholders boiled over on Dec. 20, 1860, when South Carolina became the first Southern state to announce its secession from the Union. By the time Abraham Lincoln was inaugurated as the 16th president of the United States the next year, seven Southern states had seceded to form the Confederacy.

Wikimedia CommonsHarriet Tubman guided escaped slaves through the Underground Railroad toward the North.

Black men, some of them former slaves, were recruited into the army for the first time during the Civil War in 1863. The war lasted until 1865, ending with the Union’s victory over the Confederacy, which had fought to uphold slavery.

The end of the Civil War also meant the end of the Antebellum Era and, months later, the legal abolishment of slavery through the 13th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

However, the Confederacy’s defeat awakened propaganda efforts to justify its fight to preserve slavery, spawning a distorted historical account of the Civil War known as the “Lost Cause.” This version of history was upheld by Confederacy supporters, and manifested in campaigns to erect monuments in honor of the Confederacy.

According to the Southern Poverty Law Center, 700 Confederate monuments and statues were erected after the Civil War, many built around the anniversaries of the war and periods of civil rights movements during the 20th century.

Alexander Gardner/Library of CongressAbraham Lincoln stands on the battlefield flanked by two Union operatives during the Civil War.

The myth of the Lost Cause claims that the Civil War was primarily a battle between the warring cultures of the North and the South, of which the Confederacy fought to uphold Southern morals and values despite their slim chances of victory.

This falsehood is why in some Southern states today, the Civil War is known by other names like the War of Northern Aggression and the War Between the States, even though the Confederacy’s real lost cause was to keep Black people legally enslaved.

The Whitewashing Of A Violent Era

New Line Cinemas/IMDBGone With the Wind has been described as both a pop culture classic and pro-Confederacy propaganda.

Akin to the falsehoods of Manifest Destiny and the Lost Cause meant to window-dress the ugly truths of American history, the fraught period of Antebellum America was romanticized in the decades that followed.

This distorted history was in part wrought by works of popular culture. Perhaps the most famous example is Gone With the Wind, the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel later adopted into the Oscar-winning film. It was written by Margaret Mitchell, a writer from Atlanta whose grandfather fought for the Confederacy in the Civil War.

Mitchell herself admitted that the novel’s title was a reference to how the “Antebellum civilization” was swept away by the ravages of war. The novel and subsequent film are frequently cited by historians and culture critics as an example of the glorification of the Antebellum Era and the myth of the Southern Lost Cause. As film critic Molly Haskell wrote in her 2009 book about the period film:

“‘Gone With the Wind’s portrait of a noble South, martyred to a Lost Cause, gave the region a kind of moral ascendancy that allowed it to hold the rest of the country hostage as the ‘Dixification’ virus spread west of the Mississippi and north of the Mason-Dixon Line. Generations of canny politicians, native sons espousing conservative and racist politics, dominated Washington from Reconstruction up until Civil Rights.”

Its representation of the Reconstruction era — when the former warring Union and Confederate states struggled to reintegrate after the war — depicted the time period as a great upheaval for Southern white people who had to contend with a changing American society.

Like most works of fiction with roots in history, the whitewashing of the Southern struggle during the Civil War in Gone With the Wind was treated as historical fact by some consumers. The Antebellum South transfigured from a blood-stained time in American history into a bygone golden era in the minds of many white Americans.

In the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement in 2020, some figures in the entertainment industry called for the film to be pulled from viewing. Screenwriter John Ridley, who is African American, criticized the film’s glorification of the Antebellum South, in addition to its sugar-coated depiction of slavery and its perpetuation of racist tropes.

In response, the streaming service HBO Max rereleased the film with a special introduction and discussions with historical scholars to provide audiences with proper context before watching the film.

To a larger effect, distorted representations of the Reconstruction were later used to justify the racial segregation laws of the Jim Crow era that followed. So not only was the Antebellum Period a painful time in U.S. history, it was also the foundation for more pain to come.

Next, learn the harrowing story of Cudjo Lewis, the last living slave brought to America from Africa, and then explore the true story of Ellen and William Craft, married slaves who escaped to freedom disguised as a slave owner and his valet.