Born in 1859 and shot dead at the age of just 21, Billy the Kid may have lived a short life, but it was filled with some of the most storied exploits of the Old West.

From his first robberies to his days as a frontier gunslinger to his sudden death, Billy the Kid remains perhaps the definitive legend of the Wild West. He was to outlaws what Wyatt Earp was to lawmen, an iconic figure whose larger-than-life legacy persists on to this day.

Whether it was his time with the infamous Regulators and his exploits during the Lincoln County War, or his dramatic escapes from custody culminating in his death at the hands of Sheriff Pat Garrett in 1881, Billy the Kid is one of the most mythologized figures in American history.

But how much of the myth is true? This is the real story of Billy the Kid.

Billy The Kid’s Early Days In New York And Kansas

Wikimedia CommonsA cropped version of the sole fully authenticated photo of Billy the Kid. Circa 1879-1880.

As is the case with so many mythologized historical figures, it can be difficult to separate fact from fiction. For starters, Billy the Kid’s name wasn’t Billy and he wasn’t originally from the western United States.

Born Henry McCarty, he was the first of two boys raised by a small Irish Catholic family in New York City. Nobody is sure of the exact date he was born but it seems to have been sometime in September 1859, because there’s a baptism record for him from the end of that month.

McCarty’s family life was total chaos from the start. His parents were Irish immigrants who came to America and married just after turning 20. They resided in a slum in Manhattan and his father, Patrick, did not live long.

After Patrick’s death, his widow took Henry McCarty and his brother out to Indiana, where she met a man named Bill Antrim. They all moved to Kansas in 1870 and she married Antrim in 1873. Soon after, the family moved farther west, where Henry McCarty started getting into trouble.

Henry McCarty’s Life Of Crime Begins

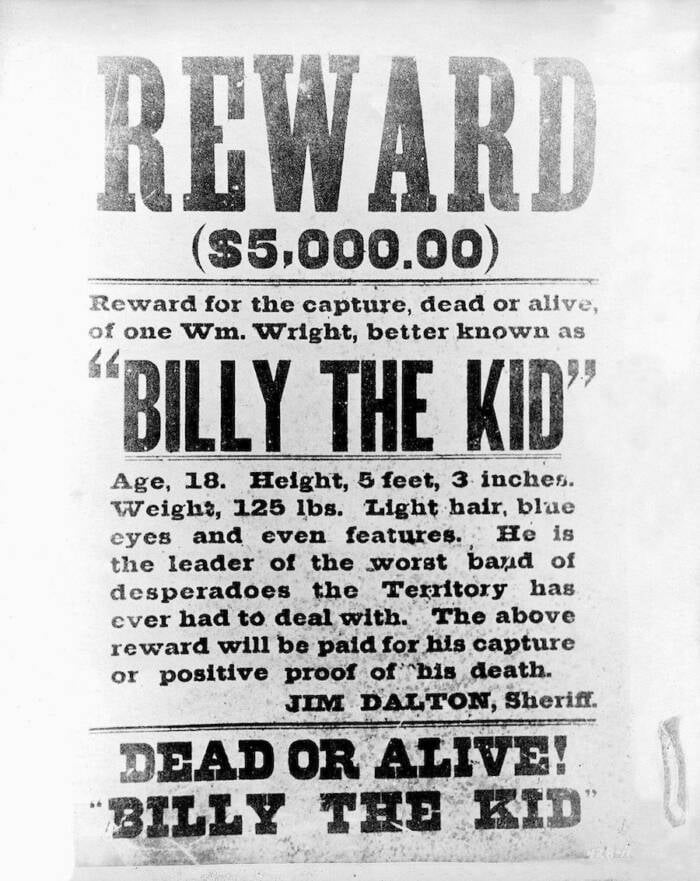

Cinematic/Alamy Stock PhotoOne of many Billy the Kid reward posters. From September 1877.

Young Henry McCarty’s new stepfather was a part-time prospector who frequently went off on extended trips. These absences became longer and more common as McCarty’s mother fell ill with tuberculosis and became more dependent on the men and boys in her family to look after her.

When she died in late 1874, Antrim was a couple of days’ ride away. He soon learned of the death, but he didn’t cut his trip short and missed the funeral. Afterward, teenage Henry McCarty was basically on his own.

He tried to work respectable jobs (such as a hotel worker and a ranch hand) but quickly found himself on the wrong side of the law. He got in trouble for petty thefts of items like food and clothing, but things got worse when he stole some pistols from a Chinese laundry in 1875 and was sent to jail.

However, just two days later, he escaped and his life as a fugitive began.

Fugitive Days In The Southwest

Wikimedia CommonsThe full-length version of the sole completely authenticated photo of Billy the Kid.

As a fugitive, Henry McCarty had to lay low. He managed to locate his stepfather’s place in New Mexico, where he holed up for a few weeks. Antrim tolerated this living situation briefly, but the two eventually had a falling out and McCarty left for good, making sure to steal a gun and some clothes on his way out. It was the last contact he ever had with Antrim.

Out on his own, McCarty slipped across the border into Arizona Territory, which technically made him a federal fugitive from justice. However, the federal government didn’t have a huge presence in Arizona Territory at the time, so McCarty was pretty much free to do as he liked.

Using the name “Billy Antrim” and nicknamed “the kid” for his youth and boyish appearance, the now 16-year-old McCarty came to be known as “Billy the Kid” and found work as a cowboy and ranch hand in Arizona. During his downtime, he liked visiting the saloon, drinking, and playing cards.

Billy the Kid was also still stealing. He and an accomplice named John Mackie began swiping horses from an Army fort and selling them. It was a good racket, but he couldn’t stay out of trouble long enough to enjoy it.

Though some say he’d previously killed several members of the Apache tribe, the first kill widely attributed to Billy the Kid happened in 1876.

During a card game, Billy the Kid accused another player of cheating. The man, a local blacksmith named Frank Cahill, called Billy a pimp. When Billy called Cahill a son of a bitch, the fight was on and soon the men were wrestling over Billy’s (stolen) revolver. Billy got the better of Cahill and shot him, inflicting a wound that would kill him the next day.

Once again, Billy the Kid was now on the run.

When he unwisely returned to the area a few days later, he was locked up in the stockade pending the arrival of law enforcement. But before that could happen, Billy snuck out of jail yet again and stole another horse, which he rode toward New Mexico Territory, where he was still wanted for robbery.

Billy The Kid’s Role In The Infamous Lincoln County War

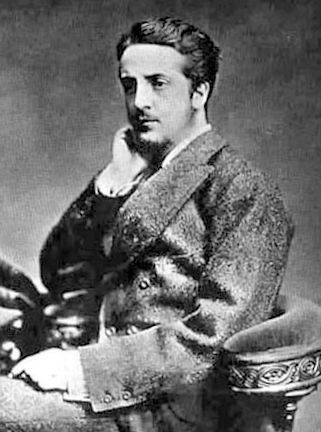

Wikimedia CommonsJohn Tunstall, a rancher who was killed in the Lincoln County War.

Billy the Kid didn’t make it all the way to New Mexico. At one point during his ride, he was surrounded by Apaches, who took his stolen horse and left him to walk through the desert for miles back to civilization. Somehow, he managed to reach a friend’s house, where he was allowed to rest.

After a week or two, he made a connection with some local cattle rustlers who made a living out of stealing cattle from a businessman named John Chisum in Lincoln County, New Mexico. However, at the same time, Billy the Kid seemed to be making an attempt at going straight.

At this point also calling himself “William Bonney,” Billy the Kid took up honest work as a cowboy for a rancher in Lincoln County named John Tunstall. But this nice, steady job for Billy the Kid soon became turbulent thanks to a dispute between Tunstall and his rivals.

In 1878, in order to settle a dispute over a large debt owed by Tunstall’s business partner to a rival cohort of local businessmen, Sheriff William Brady and his posse attempted to seize around $40,000 worth of Tunstall’s cattle. During the ensuing confrontation, the sheriff and his posse, who were loyal to Tunstall’s rivals, shot Tunstall off his horse and then picked up his own gun and used it to kill him with a shot to the back of the head.

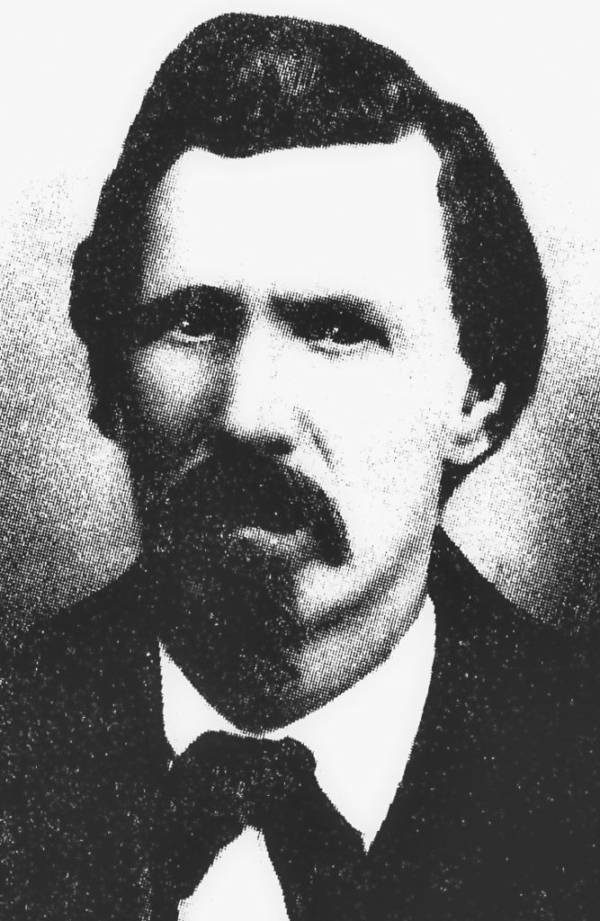

Wikimedia CommonsSheriff William Brady, a lawman who was killed by Billy the Kid and the Lincoln County Regulators.

Billy the Kid was there when it happened and went to the courts to convince them that the sheriff and his posse had committed murder. The Lincoln County justice of the peace was convinced, but before Brady could be arrested, deputies loyal to the sheriff arrested Billy and threw him in jail.

Once again, Billy didn’t stay in jail for long. But this time it was a U.S. Marshal named Robert Widenmann, there as part of a federal effort to restore order, who let him out (sparing him the hassle of planning his third jail escape).

After his release, Billy the Kid joined up with a posse called the Lincoln County Regulators in order to avenge Tunstall’s death. The Regulators were able to ambush and kill Brady, but that didn’t put an end to things.

Now, Billy the Kid and the Regulators were in trouble with the new sheriff for causing so much bloodshed. The Regulators and the new sheriff’s forces clashed in July 1878, in what’s become known as the Battle of Lincoln.

The Regulators eventually found themselves cornered and under siege in a local saloon by members of the local sheriff’s posse.

Eventually, the battle started to turn against the lawmen, but then reinforcements arrived from an Army base. At first, nobody knew which side they were there to take, but when they fell in with Brady’s men and set the saloon on fire, Billy the Kid and a few other Regulators were able to flee.

A Dramatic Escape From Custody

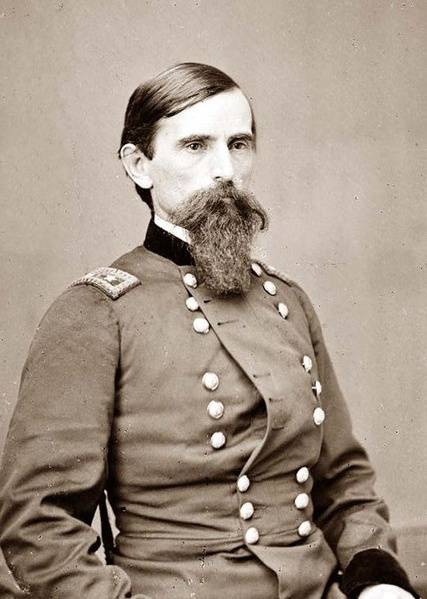

Wikimedia CommonsLew Wallace, before he became governor of New Mexico Territory.

As one of the few Regulators who’d made it out of the Battle of Lincoln, Billy the Kid was now a prime target for local law enforcement. But he came up with a plan to get himself off by providing Governor Lew Wallace with information about the murder of a lawyer that he’d witnessed recently.

He contacted the governor to exchange a witness statement for a pardon. The governor agreed and suggested that, for appearances’ sake, he should “arrest” Billy and lock him up in jail before taking his statement about the other murder. Billy agreed and went through with the farce.

About two months later with no amnesty forthcoming, Billy the Kid realized that he’d been had and they were probably going to hang him. Once again, Billy broke out of jail and went on the run.

Billy the Kid then stayed off the radar until January 1880, when he was drinking in a bar near Santa Fe. A stranger named Joe Grant came into the saloon and sidled up near the spot where Billy was drinking.

How exactly the tension mounted between Billy and Grant remains unclear (some say Billy pegged Grant for a bounty hunter who came to kill him; others say Grant was a loudmouth drunk looking for a fight). Either way, Billy sensed that trouble was coming and decided to head it off at the pass.

Thinking fast, Billy told Grant that he admired his revolver and asked if he could look at it. Noticing it only had three rounds loaded, he subtly rotated the drum to an empty cylinder and handed it back. Sure enough, after the two men antagonized each other some more, Grant did soon point his gun at Billy and pull the trigger — but all it produced was an empty click.

Billy then drew fast and shot Grant in the head before he made his escape. “It was a game of two,” Billy said, “and I got there first.”

Now the law had yet another reason to be after Billy the Kid.

“Dead, Dead, Dead!”

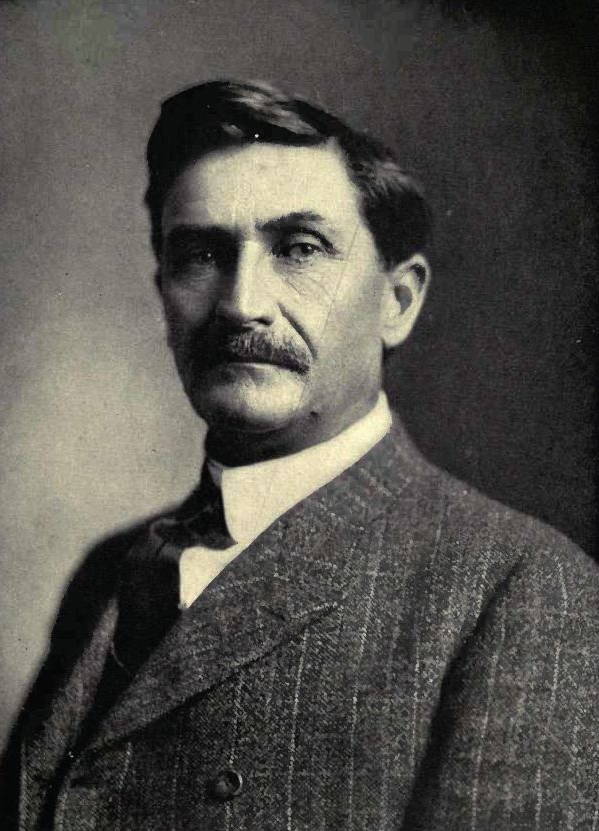

Wikimedia CommonsSheriff Pat Garrett, the man who shot Billy the Kid.

New Lincoln County Sheriff Pat Garrett and his posse captured Billy the Kid at a place called Stinking Springs on December 23, 1880. But before Garrett could get his prisoners to jail, he had to defend them from a lynch mob that had formed around the train on the route to Santa Fe. They made it safely, however, and Garrett collected the $500 state bounty on Billy’s head.

“People thought me bad before, but if ever I should get free,” Billy said after finally being captured, “I’ll let them know what bad means.”

The following spring, Billy the Kid was sentenced to death. According to legend, the judge shouted at the 21-year-old that he was to hang by the neck until he was “dead, dead, dead!” Also according to legend, Billy’s last words on the record were to tell the judge that he could go to “hell, hell, hell!”

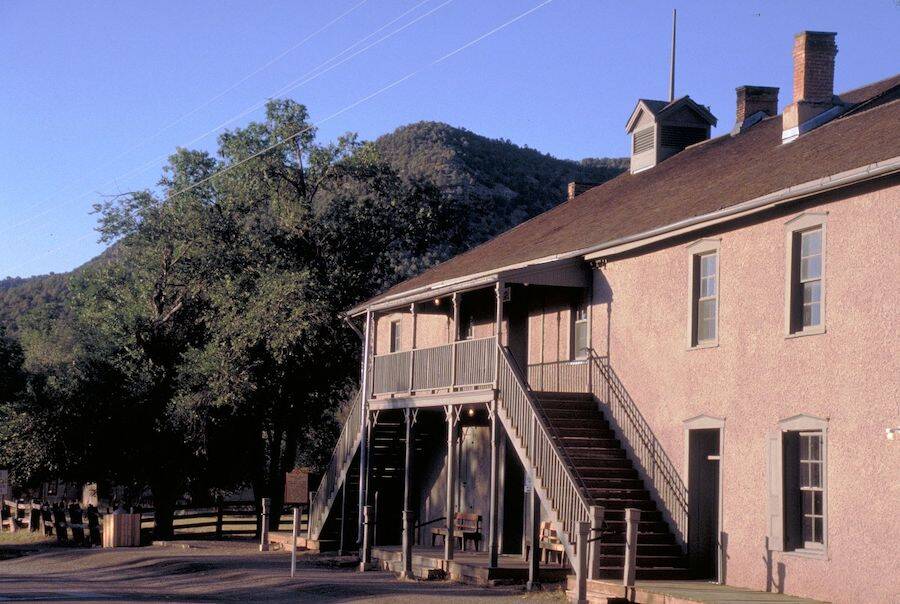

Dennis Adams/Federal Highway Administration/Wikimedia CommonsThe old jail and courthouse in Lincoln, New Mexico, where Billy the Kid was tried.

Then, on the evening of April 28, 1881, Billy was left under the supervision of a single guard in the jailhouse while the rest of the staff went to a saloon. Billy talked the guard into letting him out of his cell to use the outhouse, and then, on the way back in, he slipped off his handcuffs and beat the guard.

Stealing his gun, Billy shot him dead and hobbled (legs still shackled) to the warden’s office, where he grabbed another gun and perched in the window.

When the warden came out into the street to investigate the gunshot, Billy shouted down to him: “Look up, old boy, and see what you get!” and then he shot him dead, apparently arousing no reaction from any bystanders.

Billy the Kid then managed to cut through the shackles around his legs and steal a horse to make his escape. He then fled the town.

Pat Garrett And The Death Of Billy The Kid

Billy the Kid was free for just three months before his final encounter with Pat Garrett. The moment that word got out about his escape, New Mexico’s governor put another $500 bounty on Billy, dead or alive.

In July 1881, Garrett caught wind that Billy might be staying with a friend in Fort Sumner, New Mexico. Garrett was able to get inside the house on July 14th, and when Billy entered, Garrett shot him dead.

The infamous outlaw was dead at the age of 21.

When the governor’s office refused to give Garrett his $500 reward (for reasons that remain unclear) for killing Billy, local citizens chipped in and raised $7,000 for him instead. A little over a year later, the New Mexico territorial legislature voted to give Garrett the $500 he was owed.

Wikimedia CommonsA disputed photo bought by Randy Guijarro, allegedly showing Billy the Kid (center).

As for Billy the Kid’s legacy, he eventually became an infamous icon of American history, especially among outlaws of the Wild West. That said, some aspects of his life of crime may have been exaggerated throughout the years. While Billy the Kid once claimed to have killed 21 men — “one for every year of my life” — most experts believe he actually killed nine.

Still, some see him as a folk hero. In 1931, locals in New Mexico raised money to give him a proper headstone. And when it was stolen in 1981 and then recovered in Florida, New Mexico’s governor had it flown back home.

Throughout the years, some fans have even floated conspiracy theories that claim Billy the Kid survived to old age and that Garrett killed the wrong man or faked Billy’s death, allowing the gunslinger to live out the rest of his days under an assumed name. There’s no hard evidence that this happened, however, and most accept the official story that he indeed died in 1881.

In 2010, some petitioned the New Mexico governor’s office to grant Billy a posthumous pardon they say Lew Wallace had promised him 130 years before, but it never came to pass. That same year, a man named Randy Guijarro bought an old photo for $2 at a shop in Fresno, California.

Believing the photo to include Billy the Kid (which would make it just the second known photo of him), Guijarro found an authentication firm that verified his claim with facial recognition analysis and valued it at $5 million.

The authenticity of the photo has since been disputed, despite National Geographic standing behind it. A very similar situation arose with another disputed photo of Billy in 2017. Nevertheless, it says a lot about the continued American fascination with Billy the Kid that a mere photo of him would be valued at $5 million — more than a century after his death.

After this look at Billy the Kid, read up on other legendary Wild West figures like sharpshooter Annie Oakley and famed deputy Bass Reeves.