Just over a decade after he completed his historic flight across the Atlantic, Charles Lindbergh spoke out against American intervention in World War II, which he feared would "destroy" the "White race."

Charles Lindbergh was the first person to fly solo and nonstop across the Atlantic Ocean in 1927 — but he was only 25 years old then. He lived nearly 50 more years, through some of the 20th century’s greatest upheavals.

In the 1930s, his 20-month-old son was the victim of a gruesome kidnapping that newspapers dubbed the “Crime of the Century.” In that same decade, he publicly voiced his opposition to the United States’s intervention in World War II.

A suspected Nazi sympathizer, Lindbergh wrote articles and gave speeches stressing the importance of white racial purity, warning that a war between Germany and other European nations would “destroy the treasures of the White race.”

Lindbergh was also concerned about the environment in his later years and feared the world’s rapid industrialization would disturb nature’s equilibrium and people’s relationship with it.

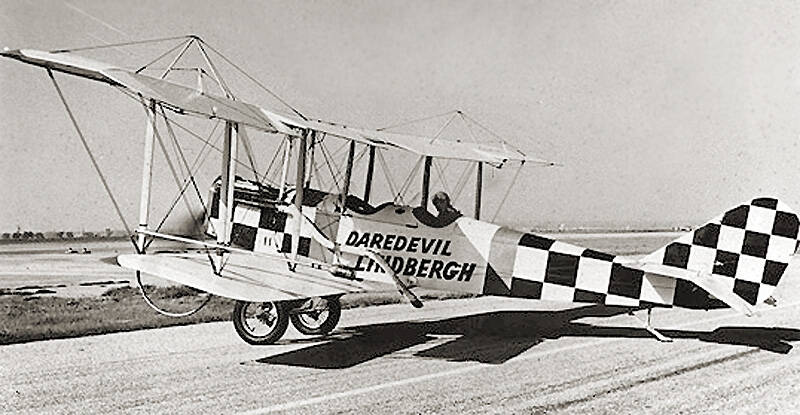

Wikimedia CommonsCharles Lindbergh sold plane rides and performed aerial acrobatics to pay the rent for a good two years.

It is this confounding complexity — a man who was a pioneer aviator, a victim of horrific violence, an espouser of hateful speech, and a conservationist — that makes Charles Lindbergh particularly difficult to pigeonhole.

Charles Lindbergh’s Early Life

Born Charles Augustus Lindbergh in Detroit, Michigan on February 4, 1902, Lindbergh spent much of his childhood in Little Falls, Minnesota and Washington, D.C., after his father was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1906.

Airplanes loomed large in Lindbergh’s early years. Before Lindbergh’s second birthday, Orville and Wilbur Wright made their first successful — albeit brief — powered flights on a North Carolina beach. In 1911, Lindbergh saw his first airplane. He later wrote:

“I was playing upstairs in our house. The sound of a distant engine drifted in through an open window. I ran to the window and climbed out onto the roof. It was an airplane! I watched it fly quickly out of sight… I used to imagine myself with wings on which I could swoop down off our roof into the valley, soaring through air from one river bank to the other, over stones of the rapids, above log jams, above the tops of trees and fences. I thought often of the men who really flew.”

In 1917, his father spoke out against U.S. intervention in World War I on the floor of the House. Not very studious, when Lindbergh heard he could skip classes and farm to support U.S. troops overseas, and still get school credit, he went for the fields as soon as he could.

World War I came to a close before Lindbergh could enlist and live out his lifelong dream of being a fighter pilot. And so he went to college and joined the Reserve Officer Training Corps instead, dropping out of school after a few semesters of failing grades and switching over to the Nebraska Aircraft Corporation Flight School in Lincoln in 1922.

The following year, he made his first solo flight in a plane his dad helped him buy, a Curtis JN4-D.

In only four years, he’d stun the world by flying across the Atlantic Ocean by himself without stopping for the first time in human history.

Wikimedia CommonsThe Daredevil Lindbergh was one of the planes Lindbergh used to perform his aerial stunts for money, before becoming the most famous aviator in American history.

In March 1924, Lindbergh sharpened his aviation skills at a U.S. Army flight school in Texas. This time, he stood out as a stellar student and graduated to the U.S. Air Service Flying School in San Antonio. Graduating at the top of his class in March of 1925, he then moved to St. Louis.

With no demand for his skills in a military capacity, Lindbergh returned to the bread and butter of civil aviation. He flew regular routes between Chicago and St. Louis as an air mail pilot.

Two years later, through a combination of ambition and a desire to make some money, he put his skills to the test for all the world to witness.

The Spirit Of St. Louis

Inspired to push the possibilities of air travel, French-American hotelier Raymond Orteig wrote a letter to the Aero Club of America in May 1919 that kicked off eight years of fierce invention and competition:

“Gentlemen, as a stimulus to courageous aviators, I desire to offer, through the auspices and regulations of the Aero Club of America, a prize of $25,000 to the first aviator of any Allied country crossing the Atlantic in one flight from Paris to New York or New York to Paris, all other details in your care.”

Coincidentally, just a few weeks later, British aviators made the first non-stop transatlantic flight. They took off from the eastern tip of Newfoundland to a small town on Ireland’s western coast, covering about 1,900 miles. The New York to Paris flight would be 3,600 miles — nearly twice as long.

Years went by without a successful attempt. A French team tried their hand in 1926, but their plane went up in flames upon takeoff. Several pilots had already crossed the Atlantic, but they had stopped on small islands along the way. By 1927, several groups were plotting their journeys, performing test flights, and tweaking their airplanes to withstand the long, fuel-heavy voyages.

With the motivation and financial support of a few generous citizens of St. Louis, Lindbergh went to work. The most imperative part of the project, of course, was constructing an aircraft that could carry enough fuel to safely reach European soil without stopping.

Wikimedia CommonsCharles Lindbergh’s Spirit of St. Louis was a modified Ryan M-2 with a Wright J5-C engine. One of the gas tanks blocked so much of his cockpit view that he had a periscope installed on the side window.

Fortunately, Lindbergh found assistance in the form of Ryan Airlines from San Diego, which agreed to retrofit one of its airplanes for his life-threatening endeavor. Engineers used the Ryan M-2 and customized it with a longer fuselage, a longer wingspan, and extra struts to carry the weight of the additional fuel.

The plane also boasted a Wright J-5C engine, manufactured by the very company founded by the Wright brothers, who achieved the world’s first successful powered airplane flight. It was a symbolic passing of the baton, from a pair of aviation revolutionaries to a new pioneer.

It was dubbed the Ryan NYP, in honor of the New York to Paris flight plan. Charles Lindbergh called it the Spirit of St. Louis.

The custom-built extra fuel tanks of the Spirit of St. Louis were situated in the plane’s nose and wings. The one upfront sat between the engine and the cockpit, which meant there was no room for a front windshield. To determine where he was, Lindbergh would have to rely solely on the plane’s side windows, a retractable periscope, and his navigational instruments.

Wikimedia CommonsWhen Charles Lindbergh landed in Paris, 100,000 people were there to greet him and celebrate his achievement.

On a damp Friday morning on May 20, 1927, the time had come. Charles Lindbergh, a mere 25 years of age, arrived at Long Island’s Roosevelt Field to make the unprecedented non-stop trip to Paris. The Spirit of St. Louis took off from the muddy runway. The next day, it landed on another continent.

Lindbergh later admitted that he kept the plane’s side windows open for the entire journey in order to stay awake. While the same route might take modern travelers a mere five or six hours, Lindbergh’s commute took a whopping 33-and-a-half.

The cold air and rain helped him stay awake and alert throughout the ordeal. Strangely enough, he also said that he hallucinated during the flight — and saw ghosts.

The sleep-deprived pilot became a world-famous figure as soon as he touched down at the Le Bourget airfield, which was Paris’s only airport at the time. A crowd of 100,000 showed up to see the Spirit of the St. Louis land. Just after 10:20 PM on May 21, 1927, Charles Lindbergh rocked the whole notion of what was capable in aviation — and he became a superstar.

Paris And New York Celebrate Lindbergh

The spectators at Le Bourget were “behaving as though Lindbergh had walked on water, not flown over it,” one observer at the scene said.

“Not since the armistice of 1918 has Paris witnessed a downright demonstration of popular enthusiasm and excitement equal to that displayed by the throngs flocking to the boulevards for news of the American flier,” wrote the New York Times.

When Lindbergh arrived in New York City on June 13, 1927, he was welcomed by four million people and a ticker-tape parade. The Times devoted its entire front page to coverage of the celebration. “People told me the New York reception would be the biggest of all,” Lindbergh wrote in a front-page column, “but I had no idea it was going to be so much more overwhelming than all the others… All I can say is that the welcome was wonderful, wonderful.”

Lindbergh was now more than a pilot — he was a bona fide American hero.

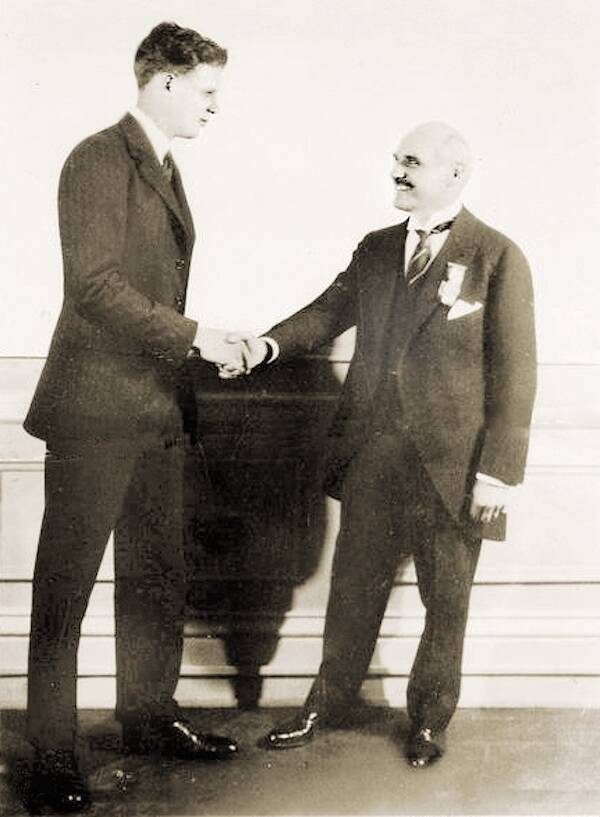

Wikimedia CommonsLindbergh accepting his $25,000 prize money from hotelier Raymond Orteig in New York. June 16, 1927.

The United States, France, and several other countries honored the aviator with awards and medals of honor, and he was promoted to the rank of colonel in July 1927. Instead of returning home and calmly pondering his accomplishment, Lindbergh flew the Spirit of St. Louis across the country and to Mexico on a goodwill celebration tour.

The smiles, cheers, and applause kept roaring for a few years. But only five years after his earth-shattering flight, Lindbergh’s fame would come to haunt him — when his infant son was kidnapped and murdered.

The Lindbergh Baby, America’s Most Famous Kidnapping

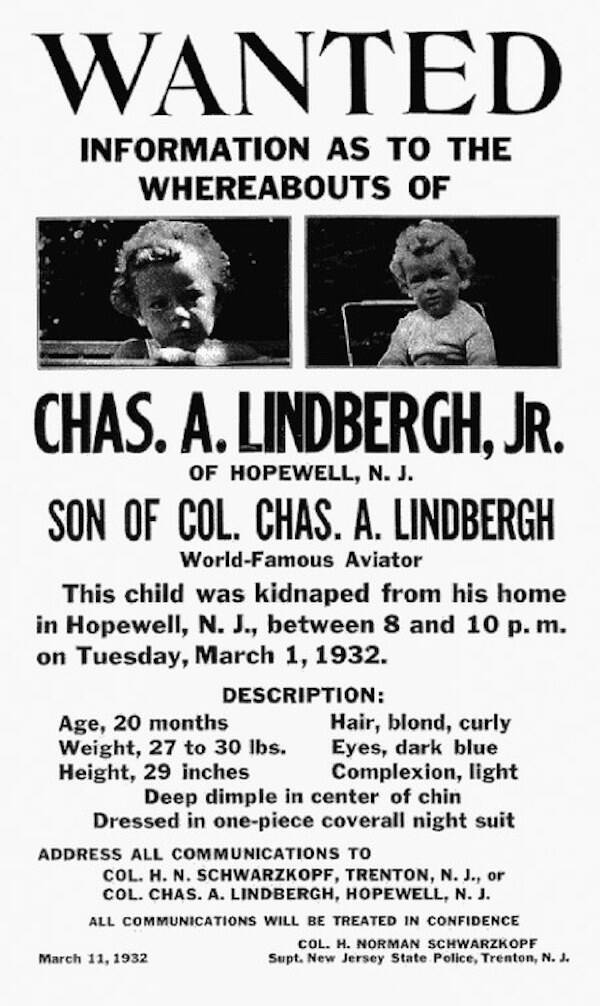

Charles Augustus Lindbergh, Jr. was only 20 months old when he was taken from his family. At around 9 PM on March 1, 1932, the infant was kidnapped from the Lindbergh’s Hopewell, New Jersey home. He was napping in the second-floor nursery.

Wikimedia CommonsThe ransom for Charles Augustus Lindbergh, Jr. kept increasing. In the end, he was found dead and a German-born Bronx resident was charged with his murder.

Caretaker Betty Gow realized the child was gone at around 10 p.m. and immediately told Lindbergh and his wife, Anne Morrow Lindbergh. They scoured the house and found a ransom note demanding $50,000. Both the local and state police began to investigate.

Muddy footprints were discovered on the floor of the nursery, and investigators found the ladder the kidnapper had used to reach the window. There was no blood or fingerprints.

Lindbergh suspected the mob may have had something to do with his son’s kidnapping. and many organized crime figures offered to help with the search — in exchange for money or shorter prison terms. One of those offers came from none other than Al Capone:

“I know how Mrs. Capone and I would feel if our son were kidnapped,” he told reporters. “If I were out of jail I could be of real assistance. I have friends all over the country who could aid in running this thing down”

On March 6, a second ransom note postmarked in Brooklyn arrived. The ransom was now $70,000. The governor called a police conference in Trenton, New Jersey, where all sorts of government officials met to discuss theories and tactics. Lindbergh’s attorney, Colonel Henry Breckenridge, hired several private investigators.

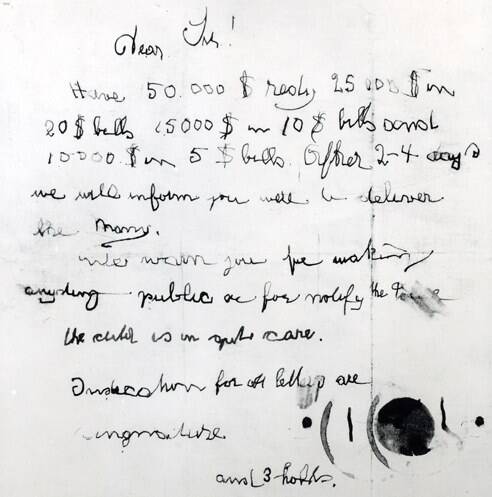

The original ransom note from the Lindbergh baby kidnapping. The author misspelled many words and used some awkward phrasing, leading investigators to believe he was foreign-born.

Breckenridge received the third ransom note two days later, which said a middle-man would not be acceptable in the ransom hand-off. That same day, however, Dr. John F. Condon, a retired school principal from the Bronx, published an offer to be the go-between in a local paper. He offered to pay an extra $1,000.

A fourth ransom note arrived the next day. Condon’s offer was accepted. Lindbergh approved of the plan. On March 10, Condon was given $70,000 in cash, and began negotiations via newspaper columns using the alias “Jafsie.”

On March 12, Condon finally met a man who called himself “John” at the Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx and discussed payment. Four days later, Condon received the infant’s pajamas as a sign of credibility. Lindbergh confirmed the pajamas belonged to his son.

The tenth ransom note on April 1, 1932, instructed Condon to have the money ready the next night. After a series of additional notes and pleading to reduce the ransom back to $50,000, Condon paid John and was told that the baby could be found on a boat named “Nellie” near the island of Martha’s Vineyard in Massachusetts.

There was nothing to be found. On May 12, however, the search came to an end. Charles Augustus Lindbergh, Jr. was found dead, decomposed, and partially buried about four and a half miles from his home. His head was crushed, there was a hole in his skull — and various body parts were missing.

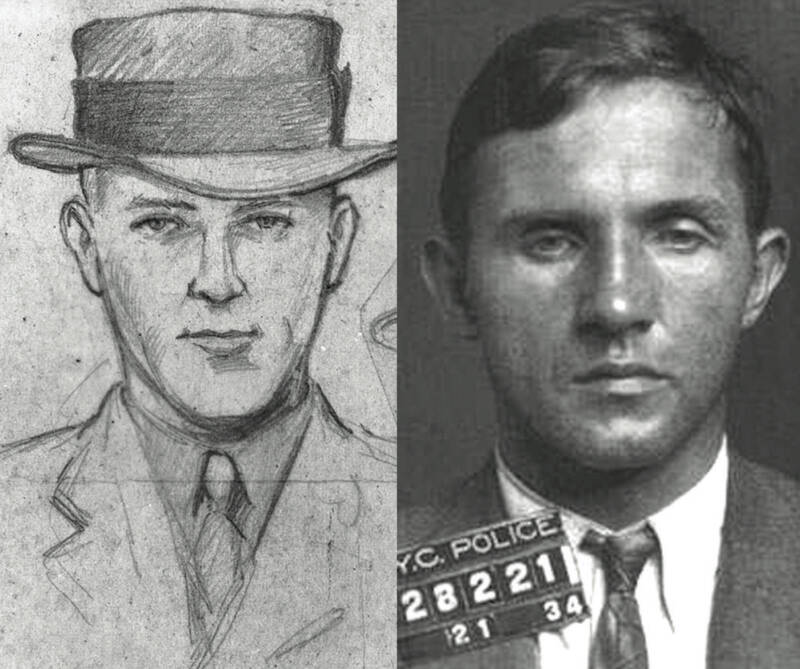

FBILindbergh representative Dr. John Condon met the mysterious man named “John.” This was how he described him to the sketch artist (left), and the eventual man charged with the baby’s murder (Bruno Richard Hauptmann; right).

A coroner estimated the child had been dead for around two months. The cause of death was a strike to the head.

FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover vowed to help bring the perpetrators to justice.

The FBI began to notify all banks in the greater New York area to look out for the ransom money — marked bills, clearly identifiable — while the state police offered $25,000 to anyone with useful information.

On Sept. 19, 1934, a 34-year-old German immigrant carpenter named Richard Hauptmann was arrested outside his home in the Bronx after he was found paying for gas using one of the ransom bills. When authorities searched his home, they found $13,000 of the ransom money, as well as other incriminating evidence.

Newspapers called it the “Crime of the Century” (this was, of course, decades before the Manson murders, Ted Bundy’s years-long murder rampage, the O.J. Simpson trial, or the Unabomber’s string of terror attacks).

Hauptmann was found guilty of murder in February 1935 and executed by electric chair on April 3, 1936.

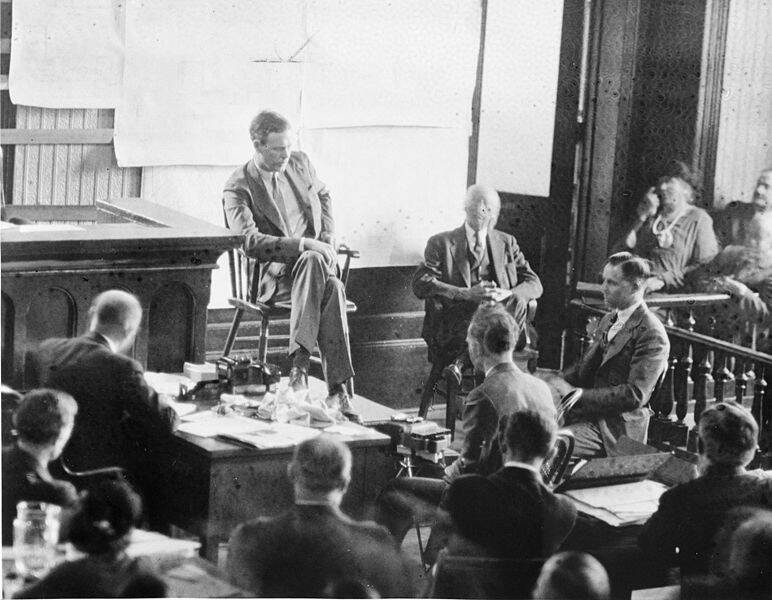

Wikimedia CommonsCharles Lindbergh, testifying at the trial of his son’s alleged killer, Richard Hauptmann, in 1935.

As a direct result of this widely publicized tragedy and consequent media fiasco, Congress passed the Lindbergh Law. This made kidnapping a federal offense, explicitly banning the use of “the mail or… interstate or foreign commerce in committing or in furtherance of the commission of the offense,” like demanding ransom.

It was now the mid-1930s, and fascism was on the rise in Europe. But the Nazi Party wasn’t only in Germany, it had a headquarters in New York City as well, and many ardent supporters in the United States. For Lindbergh, it was arguably less support of Naziism and more support of isolationism that led him to join the America First Committee. But to many observers, he certainly seemed like a Nazi sympathizer.

Charles Lindbergh And The America First Committee

On December 22, 1935, in the months between Hauptmann’s conviction and execution, the Lindberghs moved to Europe. The public attention they’d received in the wake of their son’s kidnapping and murder had become to much to handle, and they needed a semblance of peace. They lived in Britain for a few years before relocating to a small island off the coast of France in 1938.

But in early 1939, the U.S. Army called. They wanted Lindbergh to come back to the States to help assess the country’s war readiness. And so Charles and his wife settled on Long Island.

During his time in Europe, Lindbergh had visited Germany a few times per the request of American officials. They wanted him to judge Germany’s Luftwaffe for himself and report back on the country’s advancements in aviation technology. In his eyes, no power could defeat Germany’s air force – not even the United States.

In 1938, Lindbergh accepted a medal from Hermann Göring, one of the Nazi Party’s most important officials, during a dinner at the American ambassador’s house. Just a few weeks later, the Nazis carried out an anti-Jewish pogrom, later called Kristallnacht. Many thought Lindbergh should have returned his medal after the pogrom, but he refused.

Wikimedia CommonsHermann Göring presenting Charles Lindbergh with a medal on behalf of Adolf Hitler. October, 1938.

“If I were to return the German medal,” he said, “it seems to me that it would be an unnecessary insult. Even if war develops between us, I can see no gain in indulging in a spitting contest before that war begins.”

Adolf Hitler invaded Poland about a year later in September 1939, setting off World War II.

In the November 1939 issue of Reader’s Digest, Lindbergh penned an article that revealed his non-interventionist — and white supremacist — streak.

“We, the heirs of European culture,” he wrote, “are on the verge of a disastrous war, a war within our own family of nations, a war which will reduce the strength and destroy the treasures of the White race… We can have peace and security only so long as we band together to preserve that most priceless possession, our inheritance of European blood, only so long as we guard ourselves against attack by foreign armies and dilution by foreign races.”

The following year, Charles Lindbergh became the de facto spokesperson for the America First Committee, a group of about 800,000 Americans who opposed the United States entering World War II. He’d become a staunch isolationist who deemed it unnecessary to march into war — no matter what atrocities were occurring across the pond.

And he wasn’t alone: The group was funded by executives of Vick Chemical Company and Sears-Roebuck, as well as publishers of the New York Daily News and the Chicago Tribune. Among its members were future President Gerald Ford, future Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart, and future Peace Corps Director Sargent Shriver.

William C. Shrout/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty ImagesCharles Lindbergh speaks to 10,000 people at an America First rally while General Robert Wood, national chairman of the America First Committee, looks on.

To dodge accusations of anti-Semitism, the group removed from its executive committee the notorious anti-Semite Henry Ford, as well as Avery Brundage, the former head of the U.S. Olympic Committee who had prevented two Jewish runners from competing in the 1936 Olympics in Berlin.

But the anti-Semitic label stuck, in no small part due to Charles Lindbergh himself.

In what was perhaps his most famous AFC speech, delivered in Des Moines, Iowa on Sept. 11, 1941, Lindbergh identified three groups who he believed were “war agitators” hellbent on getting the U.S. involved in Europe’s conflict: the British, the Roosevelt administration — and Jews.

Through “their large ownership and influence in our motion pictures, our press, our radio, and our government,” Lindbergh believed, Jews were scaring Americans into supporting the war. Lindbergh understood why America’s Jews would want to enter World War II — to defeat Hitler, who had been gunning them down in pogroms and murdering them in concentration camps — but he felt that a war was against the interests of the United States.

“We cannot allow the natural passions and prejudices of other peoples to lead our country to destruction,” he said.

In December 1941, however, just three days after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, the AFC dissolved.

Charles Lindbergh’s Legacy

Charles Lindbergh did redeem himself in the eyes of a few, as his stance on the war changed dramatically once the U.S. effort was in full swing. He publicly supported the endeavor, and even flew 50 combat missions in the Pacific, shooting down one Japanese fighter plane.

After World War II, Lindbergh actively traveled and visited much of the world he’d never seen before. This apparently broadened his horizons, as he later claimed he garnered vital new perspectives on modern industrialization and its impact on nature.

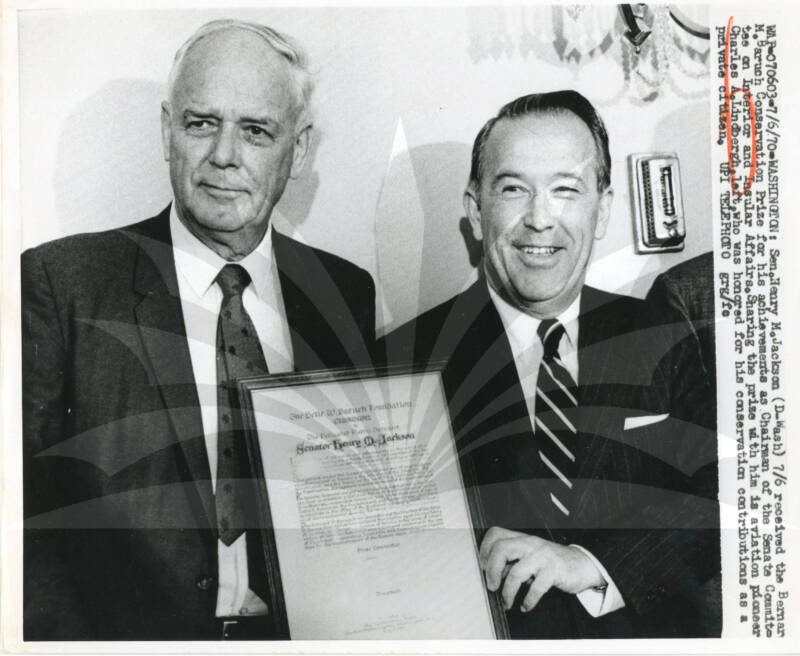

United Press International/Chapman UniversityCharles Lindbergh and U.S. Senator Henry M. Jackson receive the Bernard M. Baruch Conservation Prize. July 6, 1970.

Lindbergh said in the 1960s that he would rather have “birds than airplanes,” campaigning for the World Wildlife Fund, the International Union for Conservation of Nature, and the Nature Conservancy.

He fought to protect dozens of endangered species like blue whales, humpback whales, tortoises, and eagles. Before his death in 1974, Lindbergh even lived among several tribes in Africa and the Philippines, as well as helped secure land for the Haleakala National Park in Hawaii.

Unfortunately, however, the blemish of his anti-Jewish, pro-Nazi sentiments was irrevocable and tainted his public image to this day.

Charles Lindbergh was an impressive pilot, a onetime American hero, father to a murdered son, a seemingly pro-fascist conservative, and a lover of the environment. This complicated combination has led a large faction to despise the man as a traitorous Nazi sympathizer, while another bastion continues to hail him as an idol of ambition.

After learning about Charles Lindbergh, read about Richard Bong, America’s best fighter pilot who downed 40 enemy planes. Then, learn about Bessie Coleman, America’s first black female pilot.