A still-unidentified serial killer, Jack the Ripper murdered at least five women in London's impoverished Whitechapel district in 1888.

Warning: This article contains graphic descriptions and/or images of violent, disturbing, or otherwise potentially distressing events.

Public DomainJack the Ripper is one of the most notorious serial killers of all time, but his identity remains unknown to this day.

When Mary Ann Nichols stumbled into the night on August 30, 1888, she was filled with a hazy confidence. She lacked the money to pay for a bed at her lodging house, but she was wearing a new bonnet and was certain that she could make enough money through sex work. Just hours later, she was found brutally murdered, her bonnet “at her side.” No one knew it then, but Nichols was the first “canonical” victim of Jack the Ripper.

At first, Nichols appeared to be just another murder victim in London’s Whitechapel district, which was known for its violence. Whitechapel was overflowing with brothels and low-cost lodging houses, and it wasn’t uncommon for women like her to die violent deaths.

Still, Nichols’ murder struck police as being especially brutal, as her throat had been cut and she had been disemboweled. Then, other women started turning up dead and mutilated in eerily similar ways. The police had a serial killer on their hands.

For several terrifying weeks between August and November 1888, Jack the Ripper stalked through Whitechapel. He eventually murdered four more canonical victims — Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes, and Mary Jane Kelly — before the bloody killings seemed to abruptly stop. (In historical context, “canonical victims” refers to the women who are considered his officially accepted victims, though he may have killed others.)

Police were left with few clues: a piece of cloth, letters that may or may not have been from the killer, and of course, the crime scenes themselves, which hinted at rage toward women and sex workers in particular.

So who was Jack the Ripper? His identity remains debated to this day, and thus, the weeks that he terrorized London cast an oversized shadow across history. Could the killer have been a mentally ill hairdresser? A murderous midwife? Or even a member of the British monarchy?

Here’s everything you need to know about Jack the Ripper, from his five canonical victims, to the clues he left behind, to the most likely suspects.

Jack The Ripper’s Murder Spree Begins: The Brutal Killing Of Mary Ann Nichols

Records of the Metropolitan Police OfficeA mortuary photo of Mary Ann Nichols.

By the time Mary Ann Nichols was murdered in August 1888, a number of violent crimes had rattled police and locals in Whitechapel. In April, a sex worker named Emma Elizabeth Smith had been so brutally attacked by a group of men that she died of her injuries. Then, in August, a sex worker named Martha Tabram had been fatally stabbed almost 40 times.

These brutal events appeared to be of little concern to Nichols, a 43-year-old divorced alcoholic who’d turned to sex work to scrape by. Nichols bounced from lodging house to lodging house, and one of her roommates remembered her as being “very clean” but “melancholy.” (The roommate also acknowledged that she’d seen Nichols “the worse for drink once or twice.”)

By August 1888, Nichols was living at a lodging house at 56 Flower and Dean Street, in Whitechapel. On the night of August 30th, she squandered the few shillings she had at the Frying Pan Public House — and was turned away at her lodging house on August 31st when she tried to return around 1:20 a.m.

“Never mind,” Nichols told the night watchman. Pointing to her hat, she added: “I’ll soon get my doss money. See what a jolly bonnet I’ve got now.”

Nichols set off, presumably hoping to earn enough money through sex work to afford a bed. At around 2:30 a.m., she crossed paths with Emily Holland, a former roommate, who tried to convince her to call it a night.

“I’ve had my doss money three times today and spent it,” Nichols exclaimed. She reassured Holland: “It won’t be long before I’m back.”

But Emily Holland was the last person to see Nichols alive. About an hour later, Mary Ann Nichols was found brutally murdered on Buck’s Row.

Public DomainMary Ann Nichols is considered the first canonical victim of Jack the Ripper.

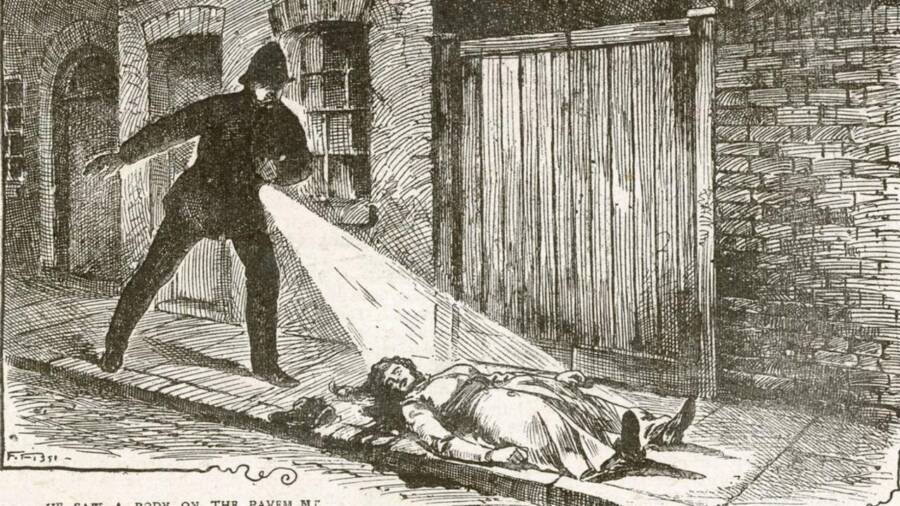

At around 3:40 a.m., a man named Charles Cross noticed a dark bundle on the ground as he made his way to work along Buck’s Row. As he approached, Cross realized it was the body of a woman. He and another man passing by, Robert Paul, examined the body. Cross thought the woman was dead; Paul thought that she was still breathing. Shortly after they set off to alert authorities, Police Constable John Neil came upon the scene.

Neil later said: “I examined the body by the aid of my lamp, and noticed blood oozing from a wound in the throat. She was lying on her back, with her clothes disarranged. I felt her arm, which was quite warm from the joints upwards. Her eyes were wide open. Her bonnet was off and lying at her side.”

An autopsy subsequently found that Mary Ann Nichols had died a shockingly violent death. Her throat had been cut, her abdomen had been sliced open, and her killer had even stabbed her in the vagina.

“I have seen many terrible cases,” Dr. Rees Ralph Llewellyn, who examined the body, told The Times, “but never such a brutal affair as this.”

But other brutal murders soon would follow. Jack the Ripper’s next canonical victim, Annie Chapman, was killed just days later.

The Murder Of Annie Chapman — And The Arrest Of John Pizer

Public DomainAll of Whitechapel was on alert in September 1888, as Jack the Ripper took more victims.

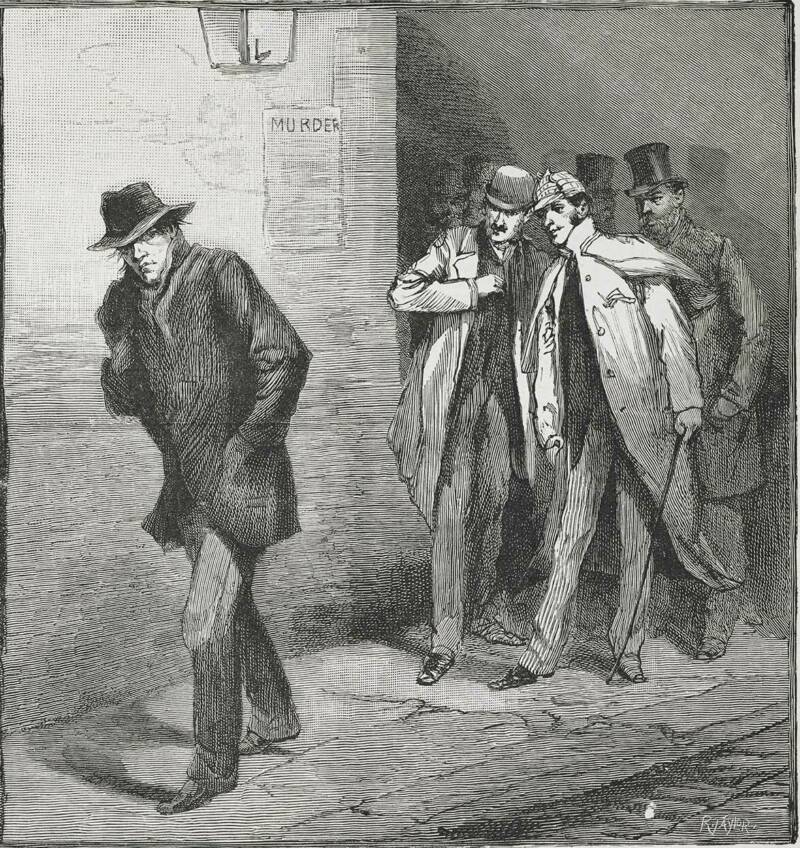

In the week that followed Mary Ann Nichols’ murder, police began speaking to local sex workers. They learned about a man known as “Leather Apron” who had a reputation for threats and violence against sex workers. Before long, newspapers in Whitechapel started to report about the suspect.

“His expression is sinister, and seems to be full of terror for the women who describe it,” The Star ominously reported on September 5, 1888. “His eyes are small and glittering. His lips are usually parted in a grin which is not only not reassuring, but excessively repellant.”

By September 7th, police had quietly identified the mysterious “Leather Apron” as John Pizer, a Polish Jew who worked as a boot finisher. “At present,” a police report noted, “there is no evidence whatsoever against him.” But then, on September 8th, another woman turned up murdered.

Her name was Annie Chapman.

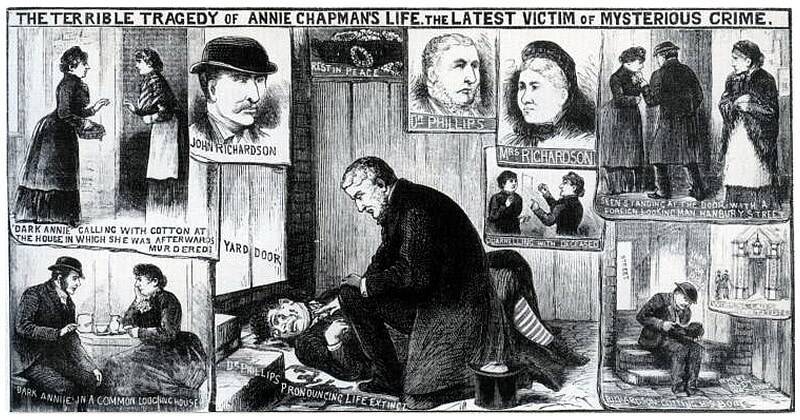

Public DomainAnnie Chapman was separated from her husband, had a drinking problem, and depended on sex work to get by.

Like Mary Ann Nichols, Chapman had a drinking problem and was separated from her husband (who eventually died, ending his financial support). And like Nichols, Chapman had turned to sex work so she could afford to live at local lodging houses. Just before her death, she was residing at a lodging house called Crossingham’s, which was located at 35 Dorset Street.

In another eerie parallel, Chapman — like Nichols — didn’t have enough money to stay at her lodging house on the night of her death. When she returned to Crossingham’s around 1:30 a.m., Chapman admitted to the house’s night watchman that she couldn’t pay for a bed yet.

“I’ll soon be back,” Chapman said. Then, she vanished into the night.

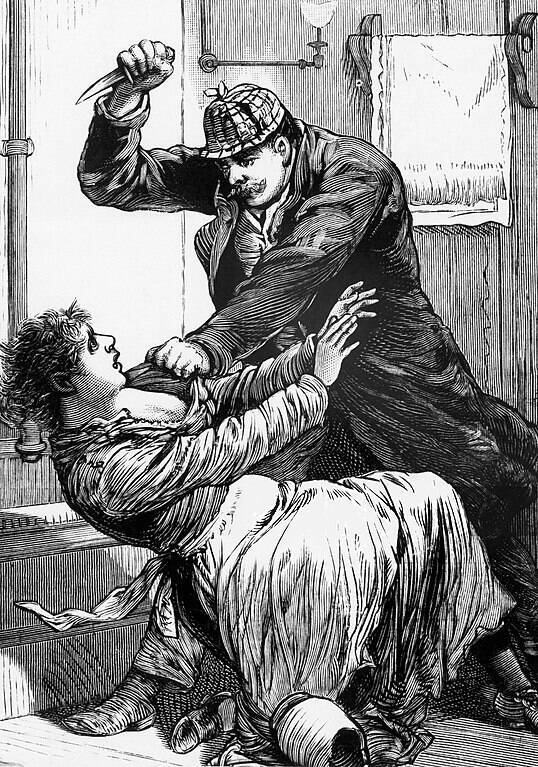

At around 5:30 a.m., a woman named Elizabeth Long saw Chapman with a man standing against a wall at No. 29 on Hanbury Street. Long later described the man as a “foreigner” who was wearing a deerstalker hat. She heard the man say, “Will you?” and Chapman reply, “Yes.”

Long then hurried on. About 30 minutes later, a resident of No. 29 Hanbury Street came across Annie Chapman’s body on the ground near the building. Her face and hands were covered in blood and her skirt was pulled up.

Illustrated Police News/Wikimedia CommonsAn illustration depicting the examination of Annie Chapman’s body.

Her murder was even more brutal than Nichols’ had been.

An inquest found that Chapman’s body “was terribly mutilated.” Her killer had cut her throat, disemboweled her, and pulled her intestines out of her body and placed them over her right shoulder. The murderer had also removed her uterus and parts of her bladder and vagina.

What’s more, a leather apron had been found at the scene. The next day, police arrested “Leather Apron” himself — John Pizer.

But investigators could find nothing to tie Pizer to the crime. His family members wholeheartedly vouched for him, there was no blood in his house or on the knives he used for boot finishing, and Pizer was able to provide solid alibis for the times of the murders of both Nichols and Chapman.

Police had no choice but to let him go. And thus, the search for Nichols and Chapman’s killer continued. Not only were local police on the case, but concerned Whitechapel residents had gotten involved too. On September 10th, a local named George Lusk formed the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee to keep an eye out for the so-called Whitechapel Murderer.

Soon, however, the killer would be known by a different name.

Jack The Ripper Gets His Infamous Name — And Murders His Third Victim

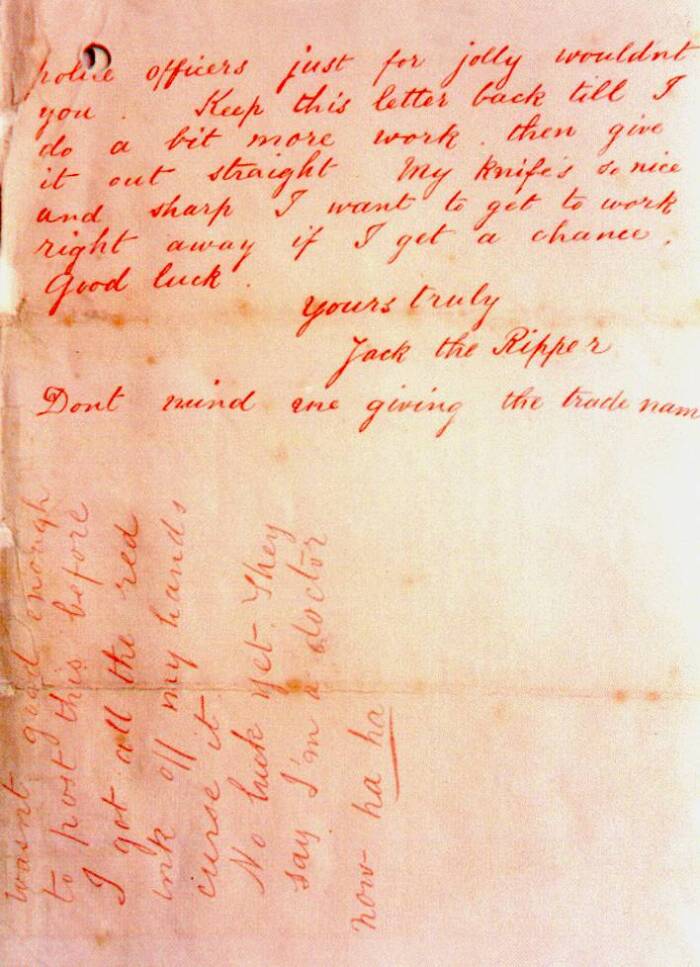

On September 27, 1888, the Central News Agency received a letter addressed to “The Boss.” The so-called “Dear Boss” letter appeared to be from the Whitechapel Murderer himself, who gleefully mocked the police.

Public DomainThe “Dear Boss” letter introduced the serial killer’s name: Jack the Ripper.

“That joke about Leather Apron gave me real fits,” the author wrote. “I am down on whores and I shant quit ripping them till I do get buckled… My knife’s so nice and sharp I want to get to work right away if I get a chance.”

Then, he wrote himself into history by signing his name — Jack the Ripper.

Whether or not the “Dear Boss” letter was authentic, the killer would forever be known as Jack the Ripper. And he would soon strike again. On September 30, 1888, the killer took his third victim: Elizabeth Stride.

Though she’d been born in Sweden as Elisabeth Gustafsdotter, Stride was cut from the same cloth as Nichols and Chapman. Separated from her husband — who died of tuberculosis in 1884 — Stride was an alcoholic who made a living as a sex worker. At the time of her death, she was residing at a lodging house at 32 Flower and Dean Street in Whitechapel.

Unlike Nichols and Chapman, however, who were forced out into the night due to a lack of funds, Stride apparently went out on her own volition. Having made a small sum of money from cleaning rooms at the lodging house, she put on a nice dress and left her residence in the evening.

That night, a number of people claimed to have seen Stride in the company of a short, respectable-looking man with dark hair and a mustache. At one point, Stride and the man were seen hugging and kissing by a pub. At another point, later in the night, a witness claimed to hear the mustached man say to Stride: “You would say anything but your prayers.”

Public DomainElizabeth Stride’s mortuary photo.

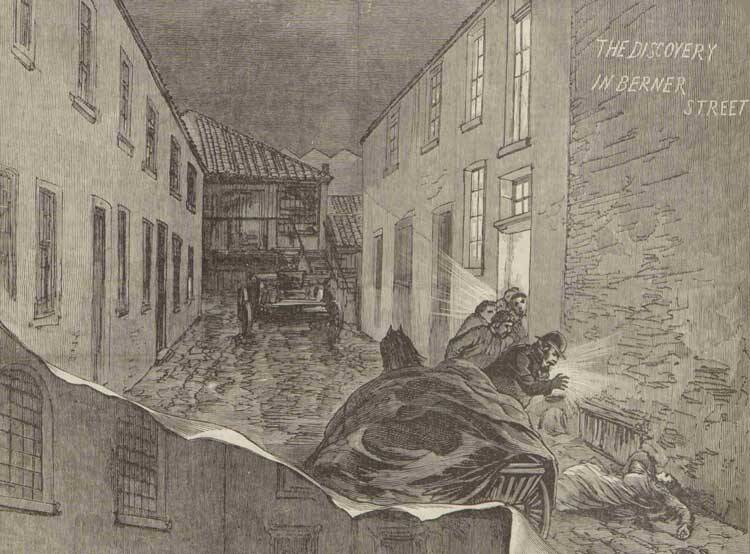

Then, around 12:45 a.m., a man named Israel Schwartz saw an alarming sight. He claimed a short man with dark hair and a mustache grabbed Stride and threw her onto the ground. A second man nearby lit his pipe, and then the first man shouted an antisemitic insult. Frightened, Schwartz fled.

Stride’s body was found 15 minutes later.

Her throat had been cut so deeply that she was nearly decapitated, but the rest of Elizabeth Stride’s body was not nearly as mutilated as Mary Ann Nichols or Annie Chapman’s had been. This led investigators to believe that Jack the Ripper had been interrupted during his murder of Stride.

Which is perhaps why the infamous killer struck again just 45 minutes later.

The Vicious Murder Of Catherine Eddowes — And The First Real Clue

Elizabeth Stride spent her last hours alive in the company of a mysterious, mustached stranger; Jack the Ripper’s fourth canonical victim Catherine Eddowes spent hers detained in a police station.

Public DomainJack the Ripper’s third and fourth victims, Elizabeth Stride (depicted in the illustration above) and Catherine Eddowes, were killed less than an hour apart.

Though poor and a heavy drinker, Eddowes was different in some ways from Nichols, Chapman, and Stride. Her friends and family adamantly claimed that she was not a sex worker (despite sources that said otherwise), and Eddowes was in a happy relationship with a man named John Kelly.

Eddowes and Kelly had spent the days leading up to Eddowes’ death trying to make money. Eventually, Eddowes said that she would ask her daughter for a loan. As the couple parted ways for what was supposed to be a brief time, Kelly allegedly told her to watch out for the Whitechapel Murderer. Eddowes purportedly waved off his concerns and responded: “Don’t you fear for me. I’ll take care of myself and I shan’t fall into his hands.”

That was the last time that Kelly ever saw her.

It’s unclear exactly how Eddowes spent her last day alive, September 29, 1888. But by 8:30 p.m., she was so drunk that the police hauled her to the Bishopsgate Police Station to sleep it off. Eddowes rested, started singing to herself, and then promised the guard on duty that she could take care of herself. So, at around 1 a.m. on September 30, 1888, he let her go. This was around the same time that police were discovering Stride’s body.

About 30 minutes later, a group of men spotted Eddowes talking with a man near Duke Street. One of them recalled that the man was fair-skinned and that he wore a red handkerchief around his throat.

But the witness didn’t stop to look closer. He hurried on. And just 15 minutes later, Eddowes was found brutally murdered in Mitre Square.

Jack the Ripper had killed Eddowes in an especially brutal fashion. Her throat was cut six or seven inches across, she’d been disemboweled, and her cheeks, eyelids, and nose were mutilated. Eddowes’ attacker had also taken her left kidney, sliced up her uterus, and removed most of her womb.

Wikimedia CommonsJack the Ripper killed Catherine Eddowes in an especially gruesome fashion — perhaps because he’d been interrupted during his murder of Elizabeth Stride.

But he’d also left behind some evidence. Police investigating the scene found a piece of Eddowes’ apron covered in blood and fecal matter in an alleyway near Goulston Street, which was about 15 minutes away from Mitre Square. This suggested that the killer had headed back into Whitechapel after murdering Eddowes. Authorities also found graffiti on a wall, which read: “The Juwes are the men that Will not be Blamed for nothing.”

Unsure if the graffiti was related to Eddowes’ murder — and well-aware of the rising antisemitism that was present in the area — the police promptly had the inflammatory words washed away.

It seemed that Jack the Ripper was escalating at an alarming pace. But it would be more than a month before the Whitechapel Murderer killed again.

The “From Hell” Letter And Jack The Ripper’s Final Victim

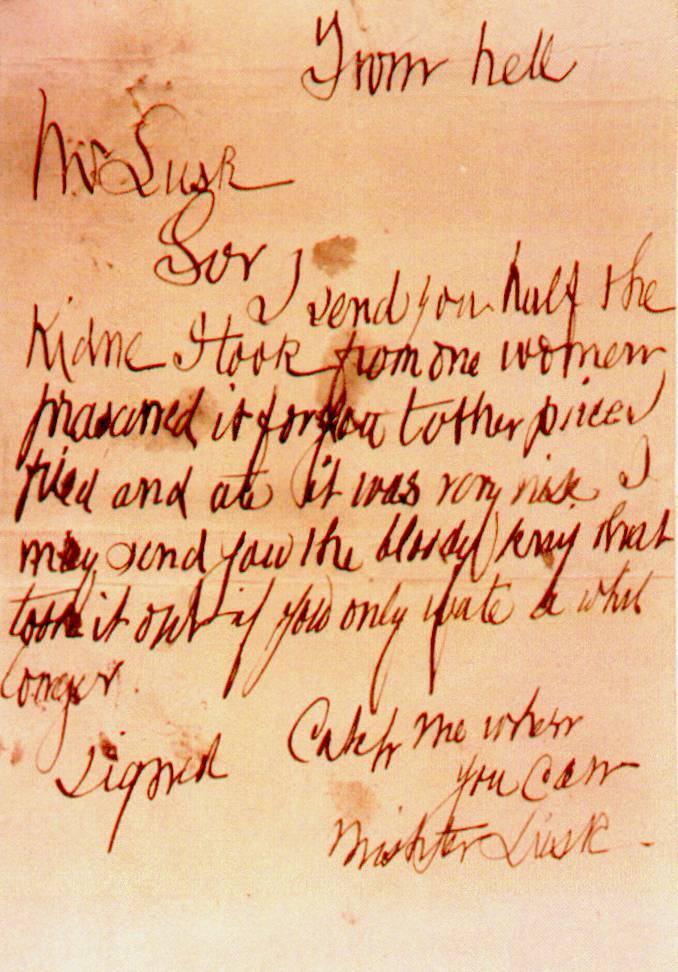

Records of Metropolitan Police ServiceThe Jack the Ripper letters are difficult to authenticate, but the “From Hell” letter arrived with a piece of a kidney that some suspected once belonged to Catherine Eddowes.

After the bloody “Double Event” — the murders of Stride and Eddowes — Jack the Ripper went quiet for a while. It wasn’t until October 16th that he resurfaced by purportedly sending a letter to George Lusk of the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee. The letter included a piece of a kidney and read:

From Hell

Mr. Lusk

Sor I send you half the Kidne I took from one women prasarved it for you tother piece I fried and ate it was very nise. I may send you the bloody knif that took it out if you only wate a whil longer.

signed

Catch me when you can Mishter Lusk

The kidney seemed to show signs of Bright’s disease. Eddowes was believed to have suffered from this condition, and the press thus speculated that the kidney included in the so-called “From Hell” letter once belonged to her.

Still, an uneasy quiet settled in Whitechapel as October bled into November. Then, on November 9, 1888, Jack the Ripper took his fifth and final canonical victim — Mary Jane Kelly. And her murder was the most horrific of them all.

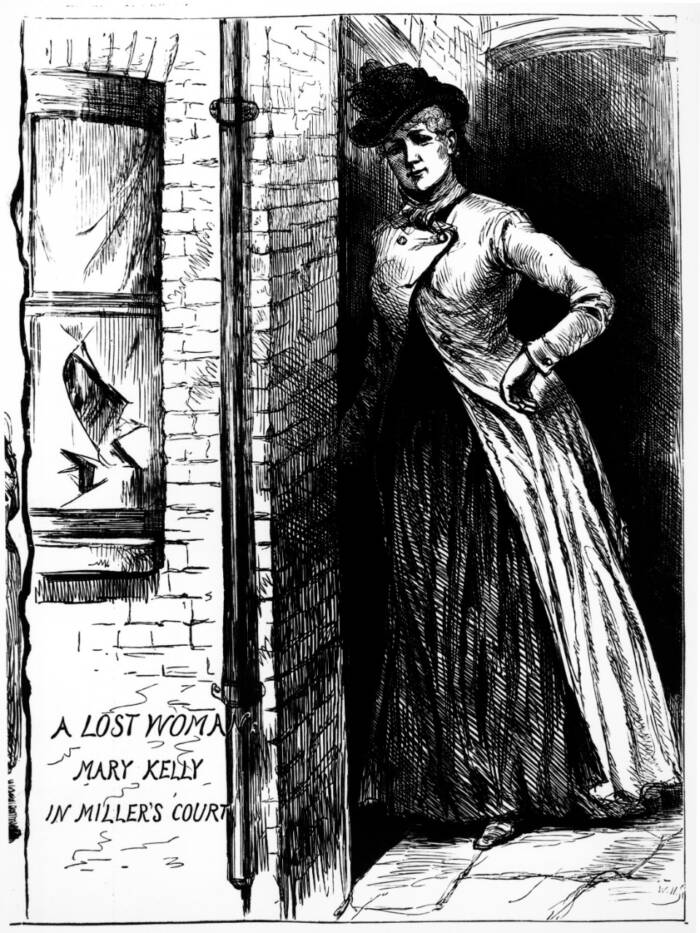

Kelly, though younger than the other Jack the Ripper victims, had trod some of the same paths as them. After making her way to London from Ireland in the 1880s, she dabbled in sex work to make ends meet.

But Kelly did not live in a lodging house at the time of her death. She lived in a room at 13 Miller’s Court on Dorset Street, which she’d shared with her on-again, off-again boyfriend, Joseph Barnett. Barnett had moved out after an argument, which meant that Kelly spent many nights there alone.

Public DomainMary Jane Kelly was Jack the Ripper’s final canonical victim.

On November 9th, around 2 a.m., a man who knew Kelly named George Hutchinson saw her strike up a conversation with a man on the corner of Commercial and Thrawl. The two exchanged a laugh, and then Hutchinson heard the man say: “You will be all right for what I have told you.”

Hutchinson watched as Kelly led the man toward Miller’s Court. He hung around for a while and then left. Around 4 a.m., two witnesses were awoken by someone crying, “Oh, murder!” (According to whitechapeljack.com, this was not an uncommon occurrence in the neighborhood.)

Later that morning, Kelly’s landlord’s assistant went to collect rent. The assistant knocked on the door, and when no one answered, he peered in the window. At first, he saw what looked like slabs of meat on the bedside table.

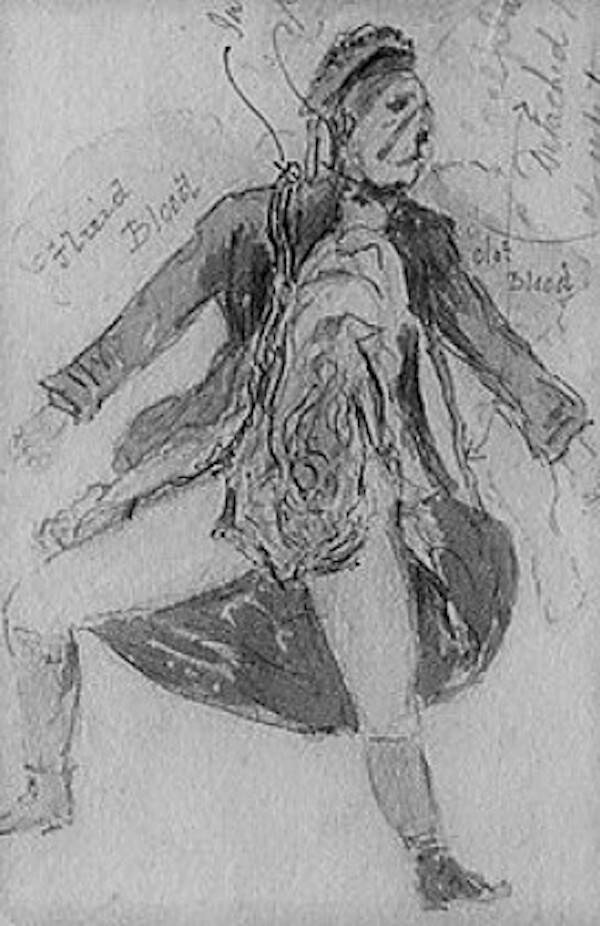

Then, he saw Kelly’s mutilated corpse.

In the privacy of 13 Miller’s Court, Jack the Ripper had committed his most brutal murder yet. Police found Kelly’s mangled body lying on her blood-soaked bed. As the postmortem report stated: “The whole of the surface of the abdomen & thighs was removed & the abdominal Cavity emptied of its viscera. The breasts were cut off, the arms mutilated by several jagged wounds & the face hacked beyond recognition of the features.”

Chillingly, some body parts were placed in different areas around the room.

Public DomainWithin the privacy of 13 Miller’s Court, Jack the Ripper gruesomely butchered Mary Jane Kelly.

Her murder showed just how hellish Jack the Ripper could be. But after Kelly’s death, the infamous serial killer seemed to stop killing. Though other women were murdered in Whitechapel in the months and years that followed, none of these crimes were tied definitively to Jack the Ripper.

And more than a century later, we still don’t know who Jack the Ripper was.

Who Was Jack The Ripper? Inside Some Of The Most Convincing Theories

Over a hundred years after Jack the Ripper terrorized the neighborhood of Whitechapel, the serial killer’s identity remains a chilling mystery. But there are plenty of theories — some more sound than others.

Two of the most intriguing Jack the Ripper suspects to emerge throughout the years are Aaron Kosminski and James Maybrick.

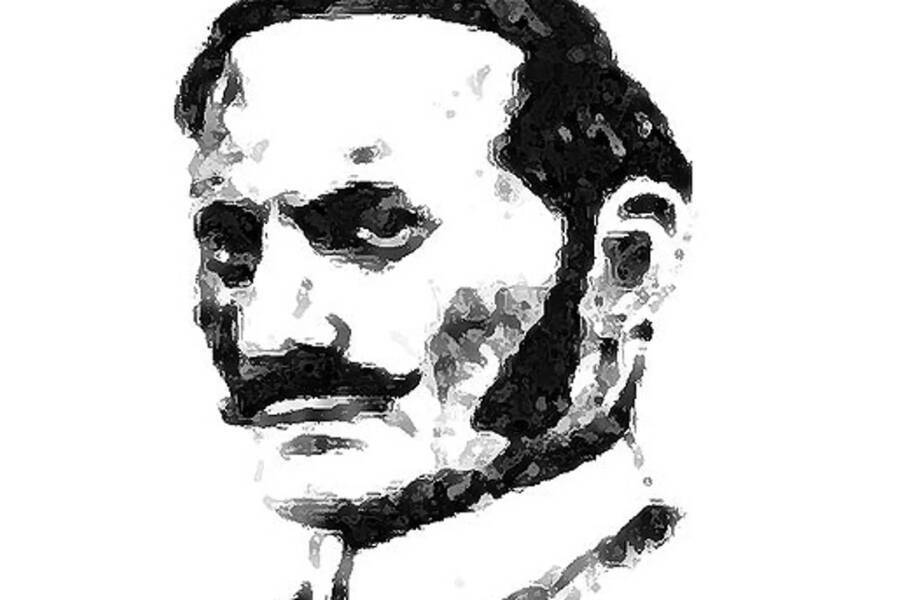

Aaron Kosminski, a Polish immigrant who worked as a barber in Whitechapel, was actually named as a suspect during the original Jack the Ripper investigation. One investigator noted that he “had a great hatred of women, especially of the prostitute class, & had strong homicidal tendencies.”

Public DomainSome believe that Aaron Kosminski was Jack the Ripper.

What’s more, some claim that DNA evidence from a shawl that belonged to Catherine Eddowes definitively links Kosminski to Eddowes’ murder.

However, many serious questions about this DNA evidence remain. The shawl was likely handled by multiple people, Eddowes could have had the DNA of multiple people on her shawl, and it’s not even confirmed that the shawl was found at any of the Jack the Ripper crime scenes.

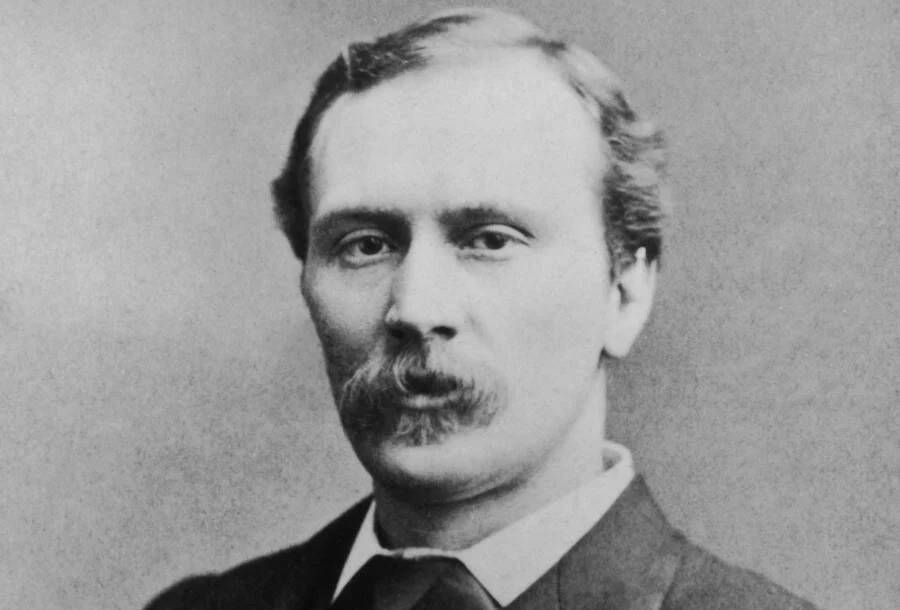

As for James Maybrick, his name appeared as a potential suspect much later. In the 1990s, a diary allegedly kept by him emerged, which seemed to contain details of the five canonical murders that only the killer would know. And the diary ends with: “I give my name that all know of me, so history do tell, what love can do to a gentleman born. Yours Truly, Jack The Ripper.”

Around the same time, a 19th-century watch also surfaced. It’s inscribed with “J. Maybrick,” “I am Jack,” and the initials of the five canonical victims.

Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesJames Maybrick is another possible Jack the Ripper suspect.

But controversy surrounds these items, as some believe the diary isn’t authentic (especially since the man who “found” it kept changing his story about how he located it). And tests on the watch were not fully conclusive.

Indeed, some people believe that Jack the Ripper was not Kosminski or Maybrick, but someone else entirely — perhaps even a murderess named Mary Pearcey or a member of the British royal family, Prince Albert Victor (but no solid evidence has ever been linked to either of them, and Victor actually wasn’t in London when most of the killings took place).

Then again, some theories claim that we’ve gotten Jack the Ripper wrong all these years. One suggests that he was not targeting sex workers, but instead people who were sleeping on the ground. Victims like Nichols and Chapman certainly had nowhere else to sleep, and this theory could explain why witnesses never heard much screaming around the times of the murders.

Another theory suggests that Jack the Ripper was looking to stoke antisemitism in Whitechapel. The area’s Jewish population had been growing in the 1880s, leading to increased tensions over unemployment, housing shortages, and immigration. This theory postulates that the killer murdered his victims to inflame anti-Jewish sentiment. After all, the “Leather Apron” suspect was Jewish, and graffiti found by Eddowes’ bloody apron referenced Jews. This all could have been a coincidence, but perhaps not.

But at the end of the day, these are all just theories. Though we can study every detail of the Jack the Ripper story — from the lives of his victims, to the streets where they were killed, to the reaction of the police — one crucial part is still missing. Jack the Ripper’s true face remains lost to time.

After reading about Jack the Ripper, discover the stories of 33 of the worst serial killers of all time. Or, look through these unsettling cold cases.