During Jack the Ripper's infamous crime spree in the autumn of 1888, the killer purportedly sent grisly letters to various journalists and officials taunting them about his murders — and one even included a human kidney.

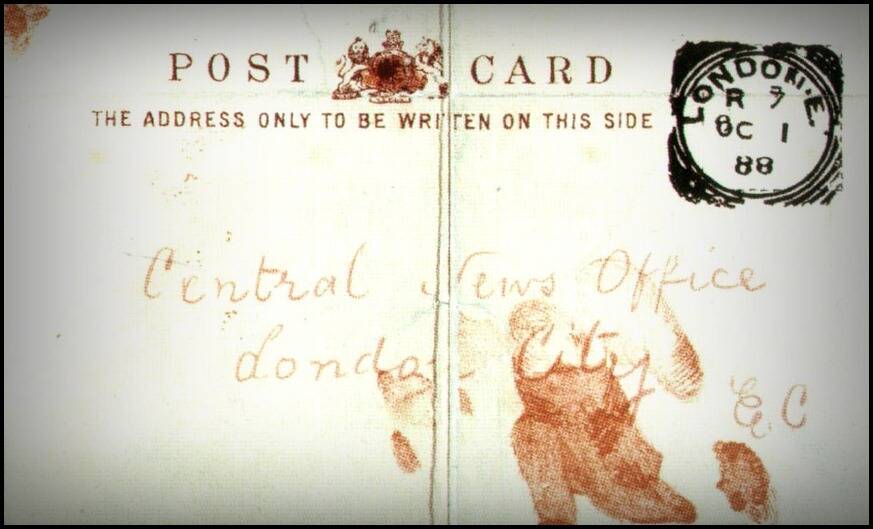

Public DomainA postcard that contained one of the Jack the Ripper letters, seemingly smeared with blood.

After murdering at least five women in 1888, Jack the Ripper seemed to disappear without a trace. He left few clues behind, and investigators have spent more than a century puzzling over his identity. But Jack the Ripper did — allegedly — send several macabre messages during his murder spree. Jack the Ripper’s letters offer a tantalizing look at the killer’s voice, handwriting, and motivations.

In fact, the London police received hundreds of letters claiming to come from Jack the Ripper. Many of these were easily dismissed as hoaxes, but others were more convincing. These include missives known as the “Dear Boss” letter, the “Saucy Jacky” postcard, the “From Hell” letter, and others.

The correspondence contained references that only the true murderer should have known, though it’s possible the messages came from journalists who had the inside scoop on the serial killer’s crimes. What’s more, one of the letters was sent alongside a real human kidney that matched the profile of one of Jack the Ripper’s victims. Still, the origin of Jack the Ripper’s letters has never been proven.

Below, discover the stories behind some of the criminal’s best-known letters — and see why they ultimately contain more questions than answers.

‘Dear Boss’: The First Of The Jack The Ripper Letters

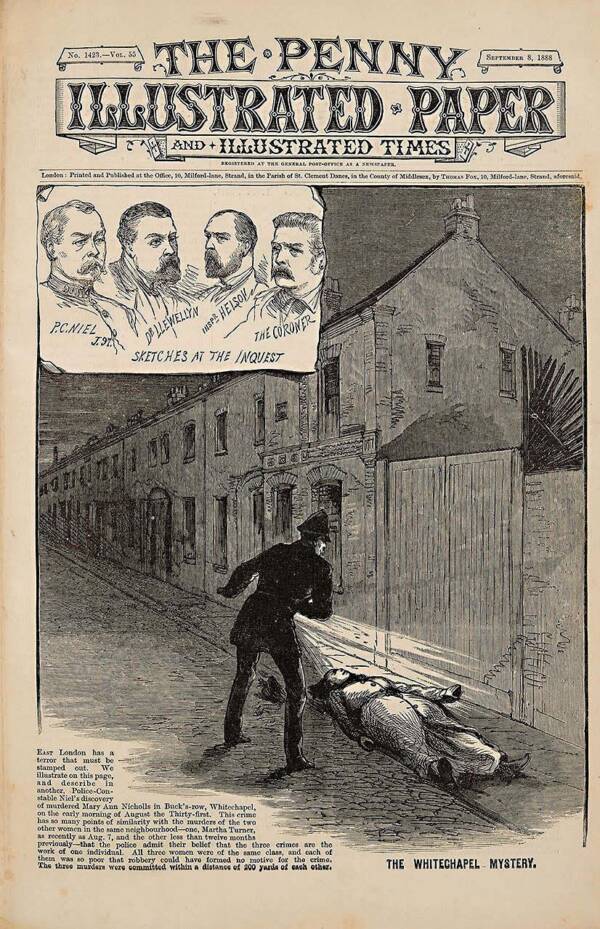

Public DomainA depiction of the discovery of Mary Ann Nichols’ body. She was the first canonical Jack the Ripper victim.

By the end of September 1888, the London district of Whitechapel was gripped by panic. Two local women — Mary Ann Nichols and Annie Chapman — had been brutally murdered by an unknown assailant. Though Whitechapel could be a dangerous place, especially for sex workers like Nichols and Chapman, their murders struck the police as especially alarming.

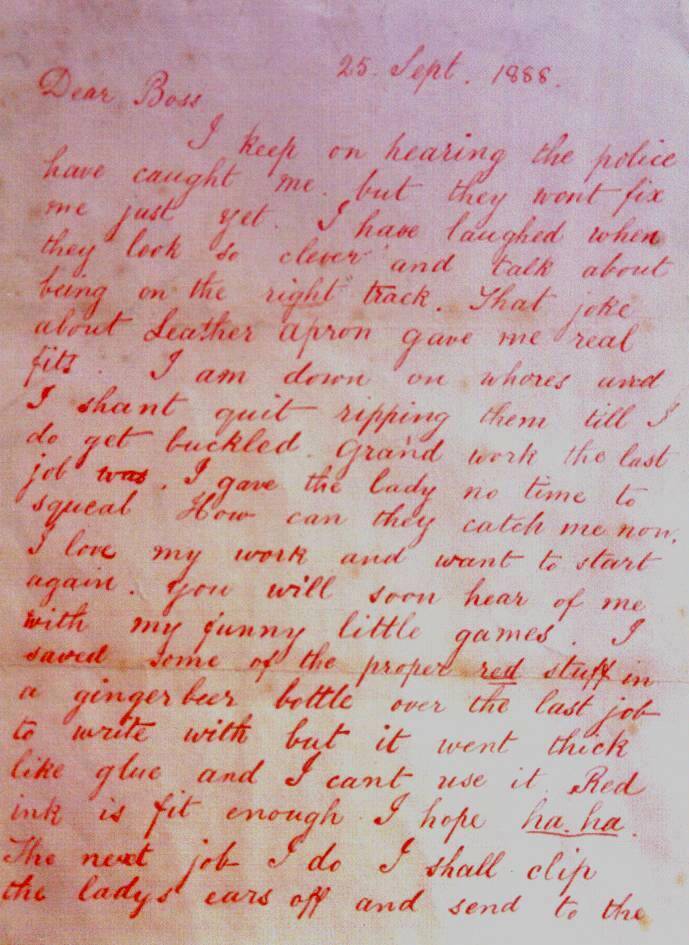

Then, on Sept. 27, 1888, the Central News Agency received a letter that claimed to come from the killer himself. Referencing a one-time suspect, a man named John Pizer, who was known as “Leather Apron,” it read:

Dear Boss,

I keep on hearing the police have caught me but they wont fix me just yet. I have laughed when they look so clever and talk about being on the right track. That joke about Leather Apron gave me real fits. I am down on whores and I shant quit ripping them till I do get buckled. Grand work the last job was. I gave the lady no time to squeal. How can they catch me now. I love my work and want to start again. You will soon hear of me with my funny little games. I saved some of the proper red stuff in a ginger beer bottle over the last job to write with but it went thick like glue and I cant use it. Red ink is fit enough I hope ha. ha. The next job I do I shall clip the ladys ears off and send to the police officers just for jolly wouldnt you. Keep this letter back till I do a bit more work, then give it out straight. My knife’s so nice and sharp I want to get to work right away if I get a chance. Good Luck.

Yours truly

Jack the RipperDont mind me giving the trade name

PS Wasnt good enough to post this before I got all the red ink off my hands curse it No luck yet. They say I’m a doctor now. ha ha

Public DomainThe text of “Dear Boss,” the first of the Jack the Ripper letters considered by some to be authentic.

With that, Nichols and Chapman’s killer had a name: Jack the Ripper. At first, however, police believed that this Jack the Ripper letter was a hoax.

Then, more women were murdered.

The ‘Saucy Jacky’ Postcard And The Murders Of Elizabeth Stride And Catherine Eddowes

Just three days after police received the “Dear Boss” letter, Jack the Ripper took two more victims. Early in the morning of Sept. 30, 1888, Elizabeth Stride was found with her throat cut in Dutfield’s Yard. Just 45 minutes later, Jack the Ripper’s fourth victim, Catherine Eddowes, was discovered brutally murdered and mutilated in Mitre Square.

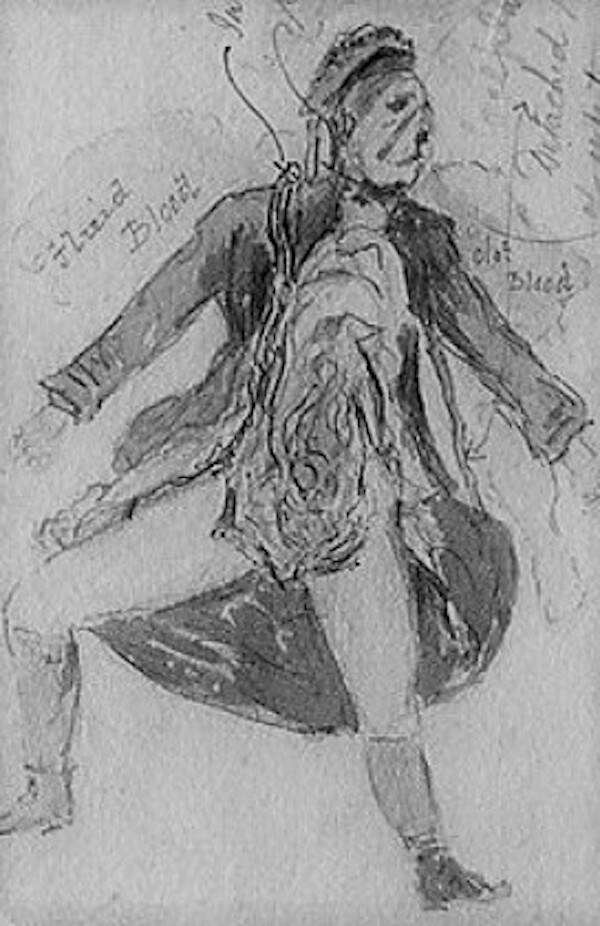

Eddowes’ murder was gruesome. Her killer had cut her throat, disemboweled her — taking her left kidney and removing most of her womb — and mutilated her cheeks, eyelids, and nose.

Public DomainA depiction of Catherine Eddowes’ mutilated body.

Significantly, her killer had also cut off a part of her earlobe, which is what Jack the Ripper had threatened to do when he said he’d “clip the ladys ears off” in the “Dear Boss” letter.

Suddenly, that Jack the Ripper letter seemed a lot more authentic. And the following day, another one arrived.

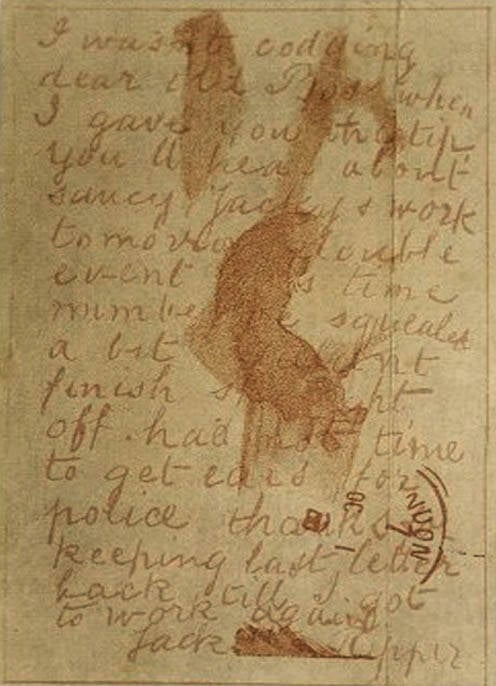

This one, known as the “Saucy Jacky” postcard, was received by the Central News Agency on Oct. 1, 1888. Seemingly smeared with blood, it read:

I was not codding dear old Boss when I gave you the tip, you’ll hear about Saucy Jacky’s work tomorrow double event this time number one squealed a bit couldn’t finish straight off. ha not the time to get ears for police. thanks for keeping last letter back till I got to work again.

Jack the Ripper

Public DomainSome of the text on the “Saucy Jacky” postcard, one of the seemingly authentic Jack the Ripper letters. It appears to be smeared with blood.

This letter struck the police as authentic for several reasons. With the line “not the time to get ears for police,” it referenced the first Jack the Ripper letter, which had not yet been made public. It also referred to a “double event,” and Stride and Eddowes had been killed less than an hour apart. Plus, the handwriting appeared similar between the two letters (and a 2018 study found that the two messages were likely written by the same person).

Though it was possible that the “Saucy Jacky” postcard was quickly written by someone who had read about the Stride-Eddowes murders in the newspaper early that morning, the police decided to publish both Jack the Ripper letters to see if anyone recognized the handwriting.

However, the most gruesome Jack the Ripper Letter was yet to come.

‘From Hell’: The Jack The Ripper Letter Sent With A Piece Of Kidney

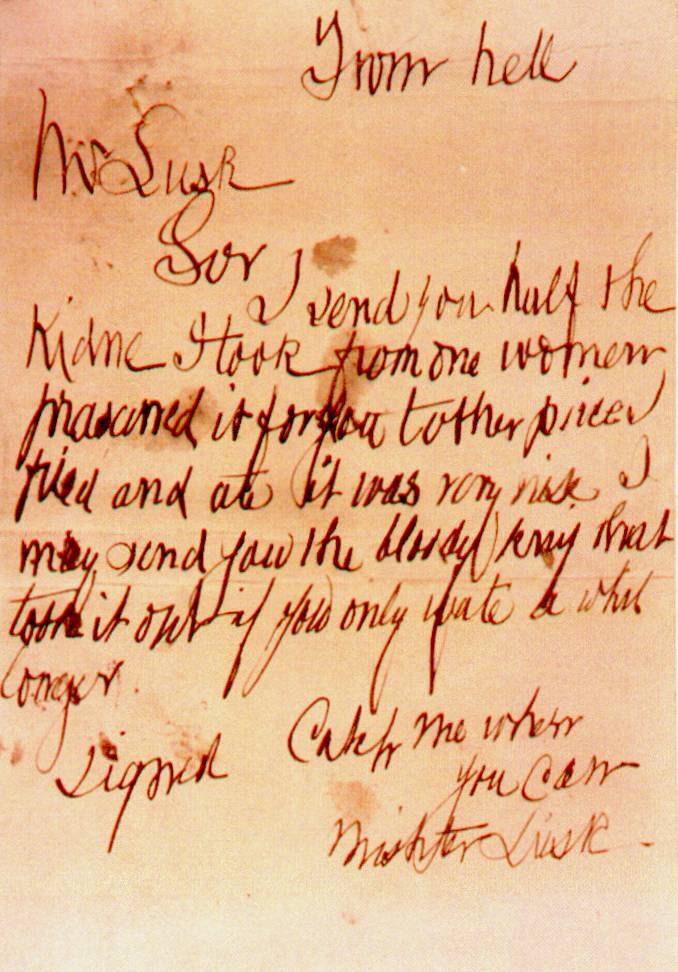

Two weeks after the “Saucy Jacky” postcard, George Lusk, a Whitechapel local who had formed the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee, received yet another Jack the Ripper letter on Oct. 16. Dubbed the “From Hell” letter, it read:

From hell

Mr Lusk,

Sor

I send you half the Kidne I took from one women prasarved it for you tother piece I fried and ate it was very nise. I may send you the bloody knif that took it out if you only wate a whil longer

signedCatch me when you can Mishter Lusk

Public DomainThe Jack the Ripper letter known as “From Hell” was sent with half of a human kidney.

But that wasn’t all. The “From Hell” letter was sent with half a human kidney. Dr. Thomas Openshaw, who examined the organ, believed that it had come from a woman around the age of 45 who had suffered from Bright’s disease, which could result from heavy drinking. Catherine Eddowes, whose killer had taken one of her kidneys, was 46 years old and an alcoholic.

The “From Hell” missive was one of the most alarming of the Jack the Ripper letters, but it was also among the last. On Nov. 8, 1888, Jack the Ripper took his final victim: Mary Jane Kelly.

Kelly’s murder was the most brutal of them all. She was mutilated and cut to pieces, and her killer had strewn her body parts around her room.

Public DomainMary Jane Kelly’s mangled corpse. Hers was the most brutal of all the canonical Jack the Ripper murders.

But then, the killer seemingly disappeared completely. So, who was Jack the Ripper? Though suspects have emerged over the years, including Polish barber Aaron Kosminski and cotton merchant James Maybrick, Jack the Ripper left very few clues behind. Perhaps the best indication of his identity and motives are his letters — but are the Jack the Ripper letters real?

Were Jack The Ripper’s Letters Legitimate?

Over the course of the Jack the Ripper murders, the police received hundreds of letters — perhaps as many as 700 — that claimed to be from the killer. Some of these were easily dismissed as hoaxes — and some of their authors were even arrested.

Public DomainA depiction of Jack the Ripper. Much remains unknown about the elusive serial killer, including whether or not any of the Jack the Ripper letters are actually legitimate.

In mid-October 1888, for example, a young woman named Maria Coroner was arrested for writing a Jack the Ripper letter which read, in part: “Perhaps you would like my portrait, but you see I am in deep mourning for those ladies that I put to sleep, and do not wish to have one taken.”

However, other messages, including the “Dear Boss” letter, the “Saucy Jacky” postcard, and the “From Hell” letter, seemed to be legitimate. Indeed, modern-day studies found that “Dear Boss,” “Saucy Jacky,” and a third letter known as “Moab and Midian” were likely written by the same person. But was that person Jack the Ripper?

Today, the Jack the Ripper letters remain a subject of debate. They may have been written by a Central News Agency employee named Thomas Bulling or perhaps a journalist named Fred Best. In 1931, Best allegedly confessed to writing “Dear Boss” and “Saucy Jacky” in order to attract more newspaper readers and “keep the business alive.”

But if some of Jack the Ripper letters are legitimate, then they’re the best clue to his identity. Long after the killer’s reign of terror, his words continue to shine through the ages, red as blood and as savage as ever.

After reading about Jack the Ripper’s letters, go inside the theory that Jack the Ripper was a woman named Mary Pearcey. Or, see why some believe that Prince Albert Victor was involved in the Jack the Ripper murders.