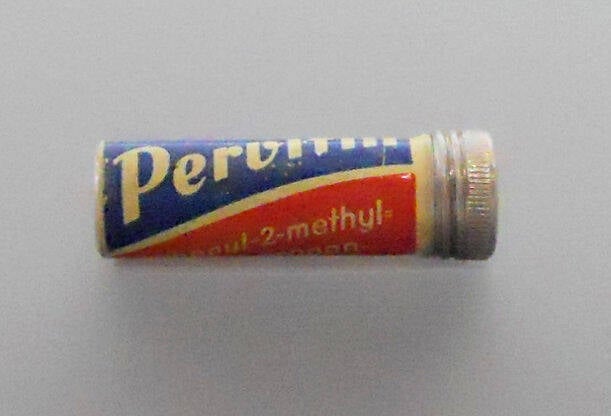

In World War II Germany, soldiers, homemakers, and even Adolf Hitler himself were all hooked on Pervitin.

Wikimedia CommonsThe German armed forces used Pervitin to soldier through tough nights, but it came at a cost. Colloquially called “panzerschokolade,” or “tank chocolate,” its creator mimicked soda packaging to market the drug.

Just before meeting with Benito Mussolini during the summer of 1943, Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler was feeling seriously ill.

Still, he couldn’t miss a meeting with another leader in the Axis powers, and so Hitler’s personal physician injected the Führer with a drug called Eukodal — a half-synthetic opioid with oxycodone — to perk him up.

The physician took a significant risk in doing so. After all, many believe that Hitler struggled with addiction to numerous drugs. But in this case, the injection seemed warranted: Hitler was suffering from spastic constipation and his stomach was in such severe pain that he couldn’t sleep.

Immediately after the first injection, a revived Hitler ordered another one. Hitler then left for the meeting with the gusto of a soldier half his age.

At the meeting with Mussolini, Hitler reportedly spoke for hours without stopping. The Italian dictator — who sat massaging his own back, dabbing his forehead with a handkerchief, and sighing — had purportedly hoped to convince Hitler to let Italy drop out of the war. He never got the chance.

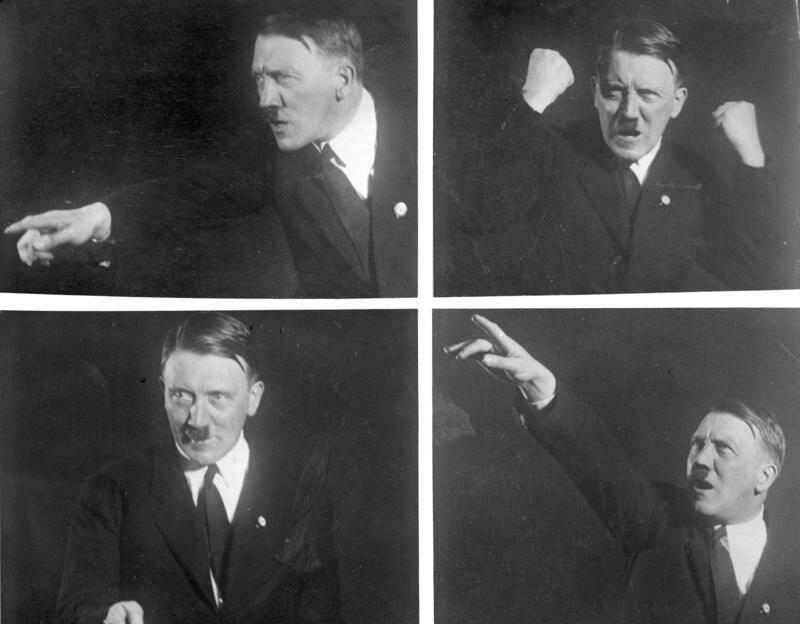

German Federal Archive/Wikimedia CommonsAdolf Hitler pushed anti-drug propaganda before reportedly becoming an addict himself.

This was but one episode amid Hitler’s drug use, which reportedly included barbiturates, testosterone, opiates, bull semen (thought to be an aphrodisiac), and stimulants like Pervitin, a “courage pill” made out of meth.

Hitler certainly wasn’t alone in his use of Pervitin. During that time period, everyone from German soldiers at the front lines to menopausal homemakers were wolfing down the pills like candy.

Widespread drug use wasn’t exactly new in the country. Germany had already been mired in large-scale drug use — that is, until Hitler rose to power amidst his anti-drug reputation. But when Hitler changed course and became an addict, the same fate apparently befell many in his country.

By the outset of World War II, German soldiers were using Pervitin to help them storm and conquer much of Europe. The high eventually vanished, however. By the end of the war, when hubris had untethered the Nazis from reality, soldiers used drugs like Pervitin simply to survive.

Writer Norman Ohler’s book, Blitzed: Drugs in Nazi Germany, tackled the role that drugs played in the Third Reich — and his claims are shocking.

Nazi Drugs: The Poison In Germany’s Veins

Georg Pahl/German Federal ArchivesDrug users purchase cocaine on the streets of Berlin in 1924.

Though he would later usher Germany into a period of heavy drug usage, Adolf Hitler first used an anti-drug platform to seize control of the country.

This platform was part and parcel of a broader campaign built upon anti-establishment rhetoric. At that time, the establishment was the Weimar Republic, the unofficial name that Hitler had coined for the German regime that ruled between 1919 and 1933 and that had grown economically dependent on drugs — specifically cocaine and heroin.

To give you an idea of this dependency’s scale, Germany was responsible for 40 percent of global morphine production between 1925 and 1930 (cocaine was a similar story), according to Ohler. All in all, with their economy largely wrecked by World War I, Germany had become the world’s drug dealer.

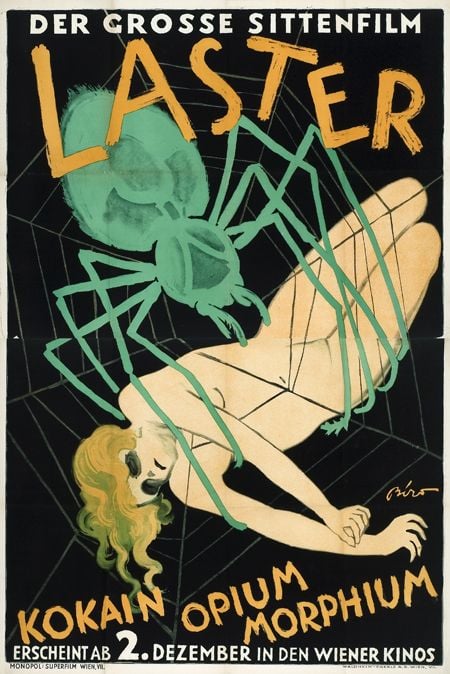

PinterestA 1927 German film poster warns of the dangers of cocaine, opium, and morphine.

Adolf Hitler wasn’t a fan of it. According to rumors, he reportedly never smoked again after throwing a pack of cigarettes into a river at the end of World War I and refused to consume alcohol.

When the Nazis took control of Germany in 1933, they began extending Hitler’s no-poison philosophy to the country as a whole. The Nazis had their work cut out for them, however. Describing the state of the country at the time of Hitler’s rise, German author Klaus Mann wrote:

“Berlin nightlife, oh boy, oh boy, the world has never seen the like! We used to have a great army, now we’ve got great perversities!”

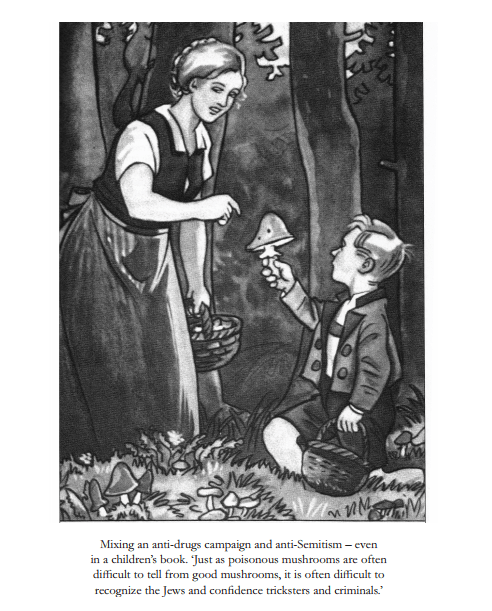

So the Nazis did what they did best, and combined their anti-drug efforts with their signature practice of accusing those they didn’t like — particularly those of Jewish descent — of being the ones stabbing Germany in the back.

The Nazis used propaganda to associate addicts with these subjugated groups, coupled with harsh laws — one early law the Reichstag passed in 1933 allowed the imprisonment of addicts for up to two years, extendable indefinitely — and secret police divisions to bolster their anti-drug efforts.

Ernst Hiemer/Norman OhlerAn illustration from The Poisonous Mushroom, as presented in Blitzed: Drugs in Nazi Germany.

The Nazis also threw medical confidentiality out the window and required doctors to refer anyone with a narcotics prescription lasting longer than two weeks to the state. Nazis restricted access to citizens and even imprisoned “undesirable” people for drug use, sending them to concentration camps. Repeat offenders of Nazi drug policies suffered the same fate.

On the surface, this large-scale shift away from rampant drug dependency may have seemed like a Nazi-induced miracle. Of course, this “miracle” only lasted until Adolf Hitler had his first taste of Pervitin.

Hitler’s Descent Into Hypocrisy

Wikimedia CommonsTheodor Morell, Adolf Hitler’s personal physician and the man responsible for introducing the dictator to harmful drugs.

In 1936, the official photographer of the Nazi Party, Heinrich Hoffmann, came down with an extreme case of gonorrhea. He was a friend of Hitler’s — he had introduced Hitler to his lover, Eva Braun, who had been Hoffmann’s assistant — and so a call went out for the best, most discreet doctor that Germany had: Theodor Morell. Known for his vitamin shots and energy injections, Morell was the “it” doctor for Berlin’s celebrities.

Morell successfully treated Hoffmann, who was so grateful for the relief that he invited Morell to his home for a meal. It was a fortuitous choice. Hitler decided to drop in that night and mentioned in passing that severe stomach discomfort and intestinal pains had tormented him for years. Not one to miss a chance to climb up the ranks, Morell offered Hitler a consultation.

Hitler took him up on his offer, later telling Morell in private that he was in so much pain that he could barely move, let alone lead a struggling country in the midst of upheaval. Morell lit up: he knew just the thing.

He prescribed Hitler a capsule full of healthy intestinal bacteria called Mutaflor, an experimental treatment at the time and one that is still used today. This helped Hitler’s stomach pain and decreased flatulence issues enough that he eventually appointed Morell as his personal physician.

From then on out, Morell would seldom leave Hitler’s vicinity, eventually injecting Hitler with everything from glucose solutions to vitamins multiple times a day, all to help relieve Hitler’s chronic pain.

Heinrich Hoffmann/German Federal Archives via Wikimedia CommonsAdolf Hitler meeting with Albert Speer, the Minister of Armaments and War Production, in 1943.

Despite these early successes, some evidence suggests that Morell grew careless after becoming Hitler’s favorite, a claim made by leading Nazi Albert Speer, Minister of Armaments and War Production. He would later write in his autobiography, dismissing Morell as a quack:

“In 1936, when my circulation and stomach rebelled . . . I called at Morell’s private office. After a superficial examination, Morell prescribed for me his intestinal bacteria, dextrose, vitamins and hormone tablets. For safety’s sake I afterward had a thorough examination by Professor von Bergmann, the specialist in internal medicine at Berlin University.

I was not suffering from any organic trouble, he concluded, but only from nervous symptoms caused by overwork. I slowed down my pace as best I could and the symptoms abated. To avoid offending Hitler I pretended that I was carefully following Morell’s instructions, and since my health improved, I became for a time Morell’s showpiece.”

Moreover, some allege that Morell was downright deceitful.

For one, Ernst-Günther Schenck, a physician in the SS who would later write a book theorizing that Hitler had Parkinson’s disease, acquired one of the vitamin packets that Morell injected into Hitler every morning and had a laboratory test it. It turns out that Morell was injecting Hitler with methamphetamine, which may explain why Hitler kept him around.

But methamphetamine wasn’t the only drug that Morell treated Hitler with: The physician would offer the Führer an ever-increasing laundry list of drugs, including caffeine, cocaine (for a sore throat), and morphine — all the drugs that Hitler had railed against for years before the war. The most significant of these drugs was Pervitin, a methamphetamine.

Pervitin And The Meth-Fueled German Spirit

Ude/Wikimedia CommonsPervitin was especially popular among Wehrmacht soldiers, but plenty of German civilians — including firemen, journalists, nurses, and homemakers — used the drug as well.

Temmler, a German pharmaceutical company, first patented Pervitin in 1937 and a German population caught up in the whirlwind of Nazism seized upon its positive effects, hoping it’d keep them alert and motivated.

Temmler commissioned one of the most successful PR agencies in Berlin to draw up a marketing plan modeled after the Coca-Cola Company, which had achieved tremendous global success by that point.

By 1938, Pervitin ads were everywhere in Berlin, from train station pillars to buses. Along with launching the PR campaign, Temmler sent each doctor in Berlin a sample of the drug in the mail, with the hope that the medical community would lead the public into the arms of Pervitin by example.

The German people indeed ignored the drug’s adverse effects, and instead focused on the energy it provided, energy very much needed in a country first rebuilding itself after World War I and then mobilizing for World War II. It was almost unpatriotic not to be hardworking, and Pervitin helped when nothing else could. Besides, it was surprisingly cheaper than coffee.

The Wehrmacht, the combined German armed forces during World War II, had a taste of methamphetamine’s power when the Nazis invaded Poland in 1939. Troops were ecstatic about Pervitin — and so were their commanders, who wrote glowing reports advocating for the use of the drug.

One drug usage report from the front lines read: “Everyone fresh and cheerful, excellent discipline. Slight euphoria and increased thirst for action. Mental encouragement, very stimulated. No accidents. Long-lasting effect. After taking four tablets, double vision and seeing colors.”

Another report read: “The feeling of hunger subsides. One particularly beneficial aspect is the appearance of a vigorous urge to work. The effect is so clear that it cannot be based on imagination.”

Prior to Pervitin, the German military had a serious issue with alcohol-driven violence, disobedience, and other infractions. The drug offered a chance for soldiers to find motivation and drive. Pervitin allowed soldiers to weather days at the front — days consisting of little sleep, copious trauma, empty stomachs, and violently enforced obedience — better than anything else.

How Pervitin Ultimately Did More Harm To The Nazis Than Good

Of course, there are consequences to distributing millions of addictive pills to as many soldiers. Addiction became a problem, with the Nazis shipping 35 million units of Pervitin and similar substances to army and air force troops in April and May 1940 alone. Letters recovered from the front show soldiers writing home, begging for more Pervitin at every turn. Everybody from generals and their staffs to infantry captains and their troops, became dependent on methamphetamine to perform their duties.

Jan Wellen/Wikimedia CommonsPervitin was initially seen as a “magic pill,” not only capable of making soldiers and citizens work harder, but also capable of curing seasickness, postpartum depression, and even “frigidity” in women.

One lieutenant colonel entrusted with running a Panzer Ersatz division described the massive drug usage in no uncertain terms, writing in a report:

“Pervitin was delivered officially before the start of the operation and distributed to the officers all the way down to the company commander for their own use and to be passed on to the troops below them with the clear instruction that it was to be used to keep them awake in the imminent operation. There was a clear order that the Panzer troop had to use Pervitin.”

He had been using the drug during battles “for four weeks taken daily 2 times 2 tabs Pervitin.” In the report, he complained of heart pains, and said his “blood circulation had been perfectly normal before the use of Pervitin.”

The writing was on the wall, and eventually, people began to take notice. In 1941, Leo Conti, the Nazi Reich Health Führer finally had enough and managed to categorize Pervitin underneath the Reich opium law — officially declaring it an intoxicant and making it illegal in the country.

Conti believed — writing in a letter, quoted in Ohler’s book — that Germany was “becoming addicted to drugs,” and Pervitin’s “disturbing aftereffects fully obliterate the entirely favorable success achieved after use… The emergence of a tolerance to Pervitin could paralyze whole sections of the population… Anyone who seeks to eliminate fatigue with Pervitin can be quite sure that it will lead to a creeping depletion of physical and psychological performance reserves, and finally to a complete breakdown.”

Methamphetamine’s long-term effects on the human body are indeed disastrous. Addiction is highly likely to swallow users whole, and with that addiction comes depression, hallucinations, severe dehydration, and constant nausea — all terrible symptoms for a soldier or a civilian.

Nazi doctors knew that these side effects couldn’t be solved by short rest periods, but could do little to prevent the ongoing abuse of Pervitin. Many soldiers who found themselves hopelessly addicted to the drug either died of heart failure, suicide, or military errors caused by mental fatigue. In the end, the drug always seemed to catch up with them.

And Conti’s attempts to rein in the Nazi state’s runaway dependence on methamphetamine was for naught. Germans barely observed the prohibition, and civilian use actually increased after the public was warned of the drug’s dangers. By that point, the military, which was about to invade Russia, had also found their dependence on the drug difficult to shake.

Perhaps most shocking, Pervitin remained accessible in Germany even after the Nazis lost the war, and it would stay that way until the 1980s.

Much like Hitler became dependent on Morell for survival, Germany became dependent on Pervitin. Germans turned to meth for the faith to endure, not realizing the harm the drug could be. And as the war dragged on, the Nazis never regained control of the pill that promised them the world.

Next, check out these absurd Nazi propaganda photos. Then, go inside the curious conspiracy theory that Adolf Hitler had Jewish ancestry.