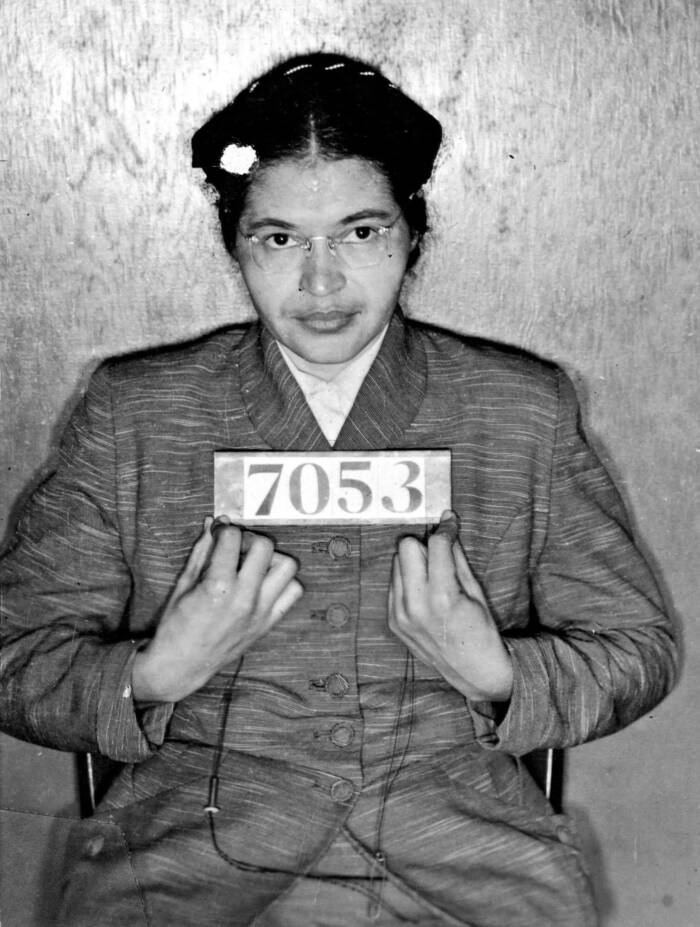

Rosa Parks' mugshot was not taken after her initial arrest for refusing to change bus seats in 1955, but was instead taken months later as Montgomery city officials attempted to intimidate her and other leaders of the Montgomery bus boycott.

Montgomery County Sheriff’s OfficeRosa Parks’ mugshot from February 1956.

Rosa Parks’ mugshot is one of the most famous images of the civil rights movement. In it, Parks holds number 7053, looking both calm and defiant. But though the Rose Parks mugshot has been linked to Parks’ arrest in December 1955 for refusing to give up her seat on a city bus, it was actually taken several months later, for a slightly different reason.

Parks had been involved in the civil rights movement since the 1930s, and soon emerged as a leader of the movement in Montgomery, Alabama. On December 1, 1955, she was famously arrested for refusing to give up her seat to a white passenger — triggering the Montgomery bus boycott.

But the Rosa Parks mugshot was not taken that day. In fact, it was not taken until February 1956, as city leaders in Montgomery tried to intimidate her and dozens of others by indicting them on an obscure charge.

Just as in December 1955, Rosa Parks refused to be cowed — which makes the Rosa Parks mugshot all the more inspirational.

Rosa Parks’ Journey Toward Becoming The Ideal “Test Case” For The Nascent Civil Rights Movement

Born on Feb. 4, 1913, in Tuskegee, Alabama, Rosa Parks (née Rosa Louise McCauley) experienced the horror of racial discrimination at a young age. When she was still a girl, she watched her grandfather, Sylvester, guard the family home with a shotgun as the Ku Klux Klan marched past. Parks also attended a segregated school and was forced to walk there and back — while her white classmates could take the bus.

Alpha Historica / Alamy Stock PhotoRosa Parks circa 1950.

As a young woman, she became more deeply involved with the nascent civil rights movement. In 1931, Parks helped organize the defense of the “Scottsboro Boys,” nine Black teenagers who’d been falsely accused of raping two white women. Her work brought her closer to Raymond Parks, an active member of the NAACP, whom Parks married in 1932.

In 1943, she joined the NAACP’s chapter in Montgomery, where she served as its youth leader and as a secretary to its president, E.D. Nixon.

In this capacity, Rosa Parks attended meetings to discuss the murder of Emmett Till, and encouraged young Black people in Montgomery to take a stand against segregation. She worked closely with Claudette Colvin, the 15-year-old who refused to change seats on a Montgomery bus in March 1955, months before Parks did. Parks also stood by Colvin even as other civil rights leaders decided that Colvin wasn’t the ideal “test case.”

Then, in December 1955, the ideal “test case” emerged — Rosa Parks herself. Her arrest on December 1 would turbocharge the civil rights movement, and lead to the iconic photo of Rosa Parks’ mugshot.

The True Story Behind Rosa Parks’ Mugshot

Photo 12/Alamy Stock PhotoRosa Parks sitting on a Montgomery bus in 1956.

On Dec. 1, 1955, Rosa Parks boarded a Montgomery bus after a long day of work at a Montgomery department store. At the time, buses in Montgomery were segregated, and Parks took a seat in the “colored” section. But as the bus got full, the driver, James F. Blake, demanded that Black passengers give up their seats to white passengers. Many compiled; Rosa Parks refused.

“I don’t think I should have to stand up,” Parks told the driver. Blake promptly called the police, who arrested her for violating Chapter 6, Section 11, of the Montgomery City Code.

“Just having paid for a seat and riding for only a couple of blocks and then having to stand was too much,” Parks said in a 1995 interview with the Academy of Achievement. “These other persons had got on the bus after I did. It meant that I didn’t have a right to do anything but get on the bus, give them my fare, and then be pushed wherever they wanted me… There had to be a stopping place, and this seemed to have been the place for me to stop being pushed around and to find out what human rights I had, if any.”

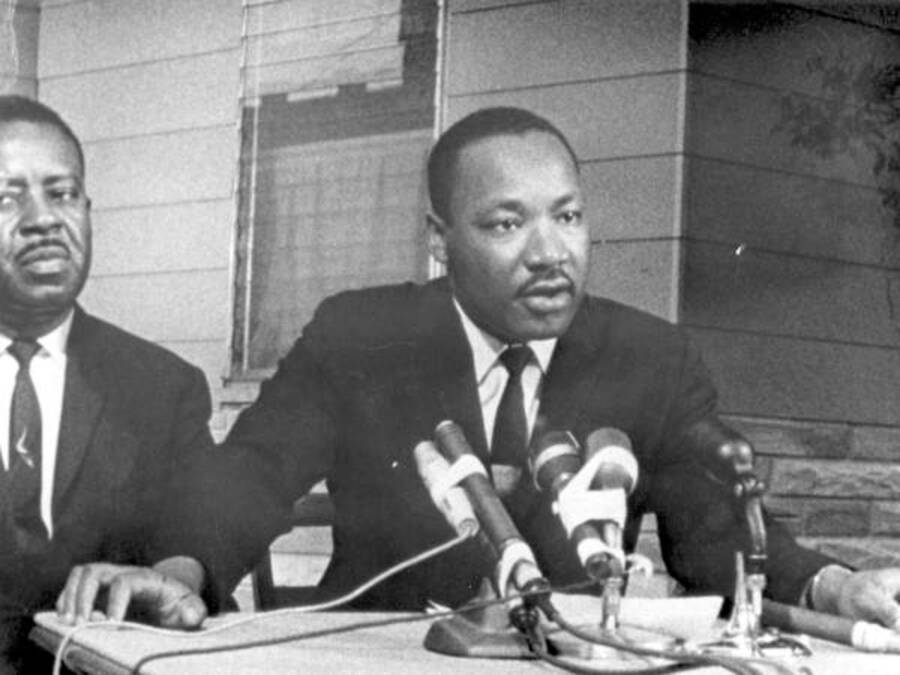

In the aftermath, the civil rights movement began to gain steam. Black leaders in Montgomery formed the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) and asked a young preacher named Martin Luther King Jr. to help lead them. And on the day that Rosa Parks was arraigned, Dec. 5, 1955, the Montgomery bus boycott began. The 40,000-some Black citizens of Montgomery stopped riding the city buses — effectively emptying them out.

“We are … asking every Negro to stay off the buses Monday in protest of the arrest and trial,” pamphlets distributed by the Women’s Political Council stated. “If you work, take a cab, or walk. But please, children and grown-ups, don’t ride the bus at all on Monday. Please stay off the buses Monday.”

The boycott was originally planned to last just one day. Instead, it would continue for 381 days — and change American history.

State Archives of Florida / Florida Memory / Alamy Stock PhotoMartin Luther King Jr. emerged as a leader of the Montgomery bus boycott, and the civil rights movement at large.

The Montgomery bus boycott disrupted city life and crippled the bus company’s finances. Segregationists responded with fury, bombing the homes of King and Nixon. And the city began to target its organizers, including Rosa Parks.

On Feb 22, 1956, Parks and 88 other civil rights leaders were arrested. City leaders charged them with an antiquated anti-syndicalism law, which, according to the Equal Justice Initiative, accused Parks and the others of violating a 1921 statute forbidding boycotts without “just cause.”

“In this state we are committed to segregation by custom and law; we intend to maintain it,” the grand jury report stated. “The settlement of differences over school attendance, public transportation and other facilities must be made within those laws which reflect our way of life.”

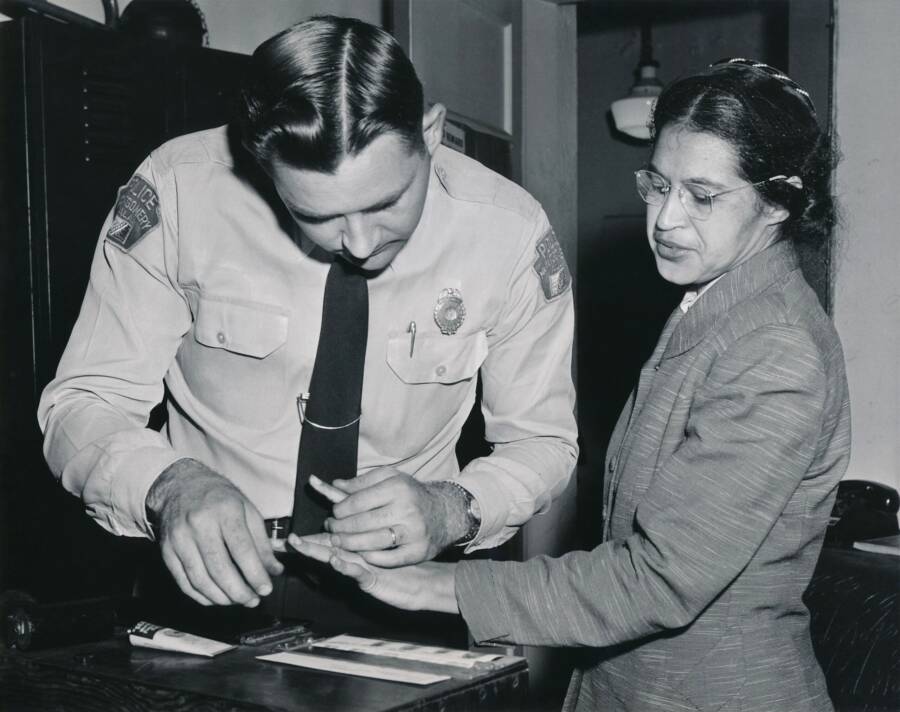

Rosa Parks’ mugshot — as well as a photo of Parks being fingerprinted by a police officer — thus stem from her arrest in February 1956.

Public DomainRosa Parks’ mugshot and this photo of her being fingerprinted both stem from her 1956 arrest, months after her initial arrest for refusing to move seats on the bus.

But if city leaders — and segregationists around the country — hoped that the indictments would quell the civil rights movement, they were badly mistaken. On December 20, 1956, the city agreed to end segregation on its buses. And both Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King Jr. became symbols of the civil rights movement.

But Rosa Parks’ life in the aftermath would not be easy.

How Rosa Parks’ Mugshot Changed Her Life

Though activists like Rosa Parks and her husband had been fighting segregation quietly for decades, the Montgomery bus boycott marked the beginning of a new, bigger phase of the civil rights movement. But it also made life difficult for the couple.

Both Rosa Parks and her husband lost their jobs during the bus boycott. In fact, neither would ever find work in Montgomery ever again. Though they moved to Detroit in 1957, they struggled to find work there as well, and it wasn’t until Parks got a job with U.S. Representative John Conyers in 1966 that they were able to earn what they had made back in Montgomery.

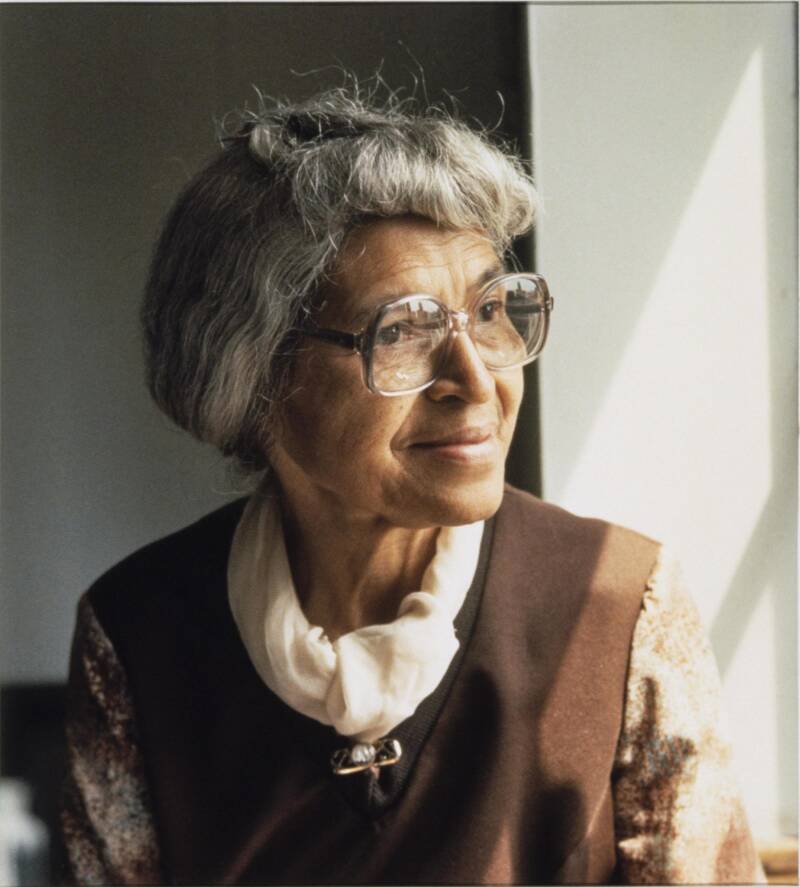

Harvard UniversityRosa Parks in 1978.

Despite this, Parks remained involved in the civil rights movement. Finding that the North was the “promised land that wasn’t,” she fought against housing discrimination, school segregation, employment discrimination, and police brutality. Parks also came to admire the fiery oratory of Malcolm X, calling him her personal hero.

“I don’t believe in gradualism,” she stated in 1995, “or that whatever is to be done for the better should take forever to do.”

In the end, Rosa Parks’ mugshot came to symbolize the early days of the civil rights movement. But it’s also a good representation of Parks herself. Determined, defiant, and courageous, her brave stand in 1955 — and beyond — would change the course of American history.

After discovering the true story of the Rosa Parks mugshot, read about the inspirational civil rights leaders who you never learned about in school. Or, see how Ruby Bridges transformed the civil rights movement — at the age of just six years old.