Throughout the Civil War, Reconstruction, and the early years of the Gilded Age, Thomas Nast used his political cartoons published in Harper's Weekly to satirize current events, expose corruption, and even influence elections.

In the second half of the 19th century, one of the most powerful political voices in the United States was not a politician or a president, but a cartoonist. Thomas Nast’s cartoons in Harper’s Weekly made him one of the loudest and most influential voices of his time.

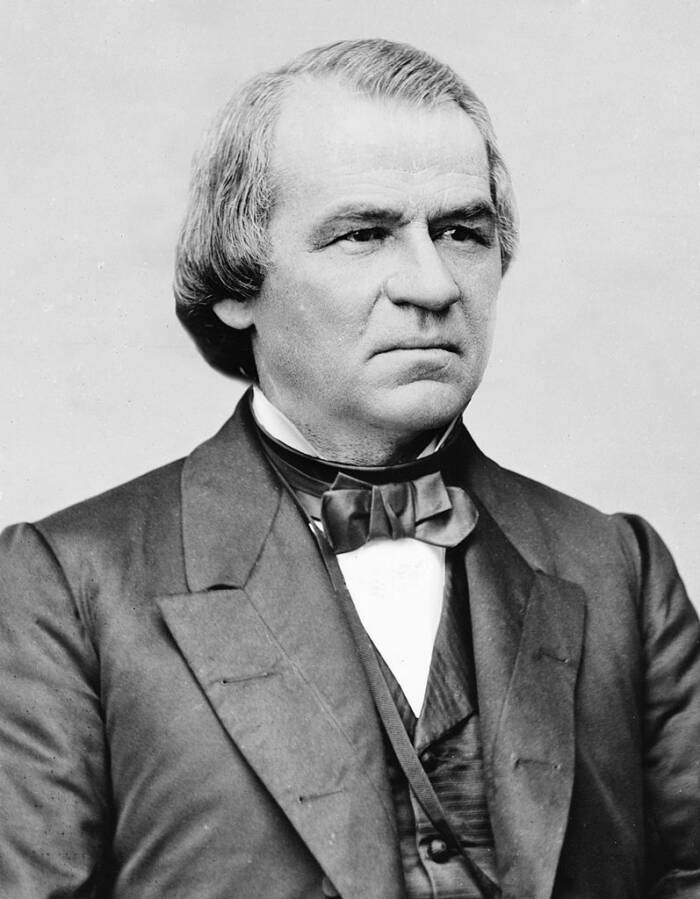

Nast's career began in the 1860s, and he went on to produce more than 2,000 cartoons. An ardent Republican, his cartoons were shouts of support for Abraham Lincoln, Reconstruction, and racial equality — and vicious critiques of Andrew Johnson, ex-Confederates, and carpetbaggers.

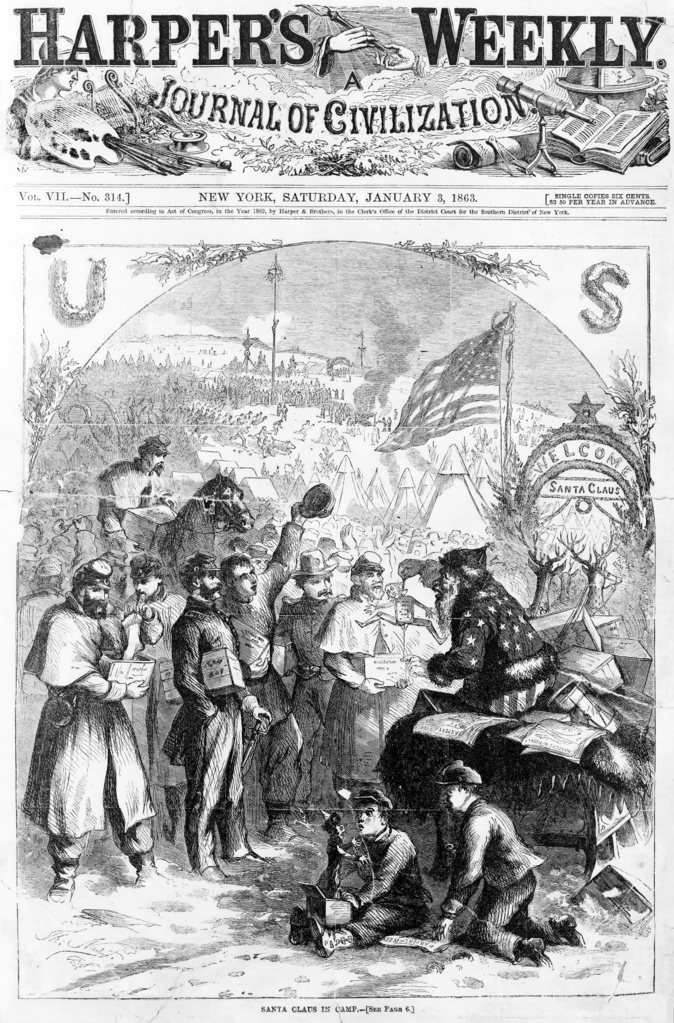

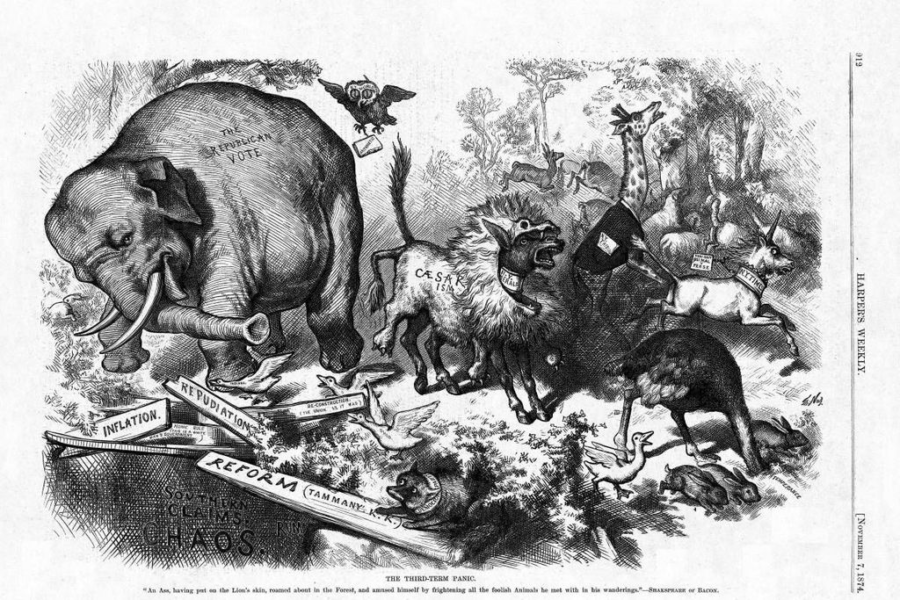

What's more, Thomas Nast's cartoons would help associate Democrats with donkeys and Republicans with elephants. He would even cement the modern images of Santa Claus and Uncle Sam in the popular American imagination.

In the gallery above, look through a collection of Thomas Nast's cartoons. And below, read on to see how Nast's illustrations influenced American politics and history.

Who Was Thomas Nast?

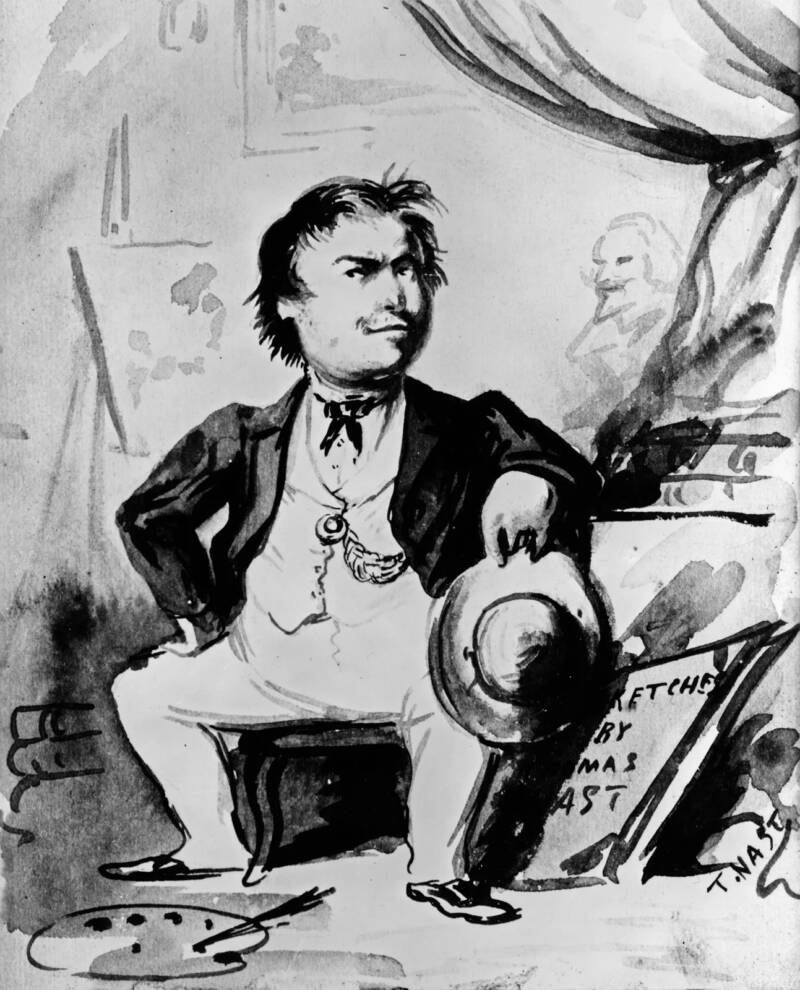

Library of CongressThomas Nast, by Thomas Nast. 1859.

Born on Sept. 26, 1840, in Germany, Thomas Nast arrived in the United States at the age of six. He studied at the National Academy of Design as a young man and, in 1862, began a fateful career with Harper's Weekly.

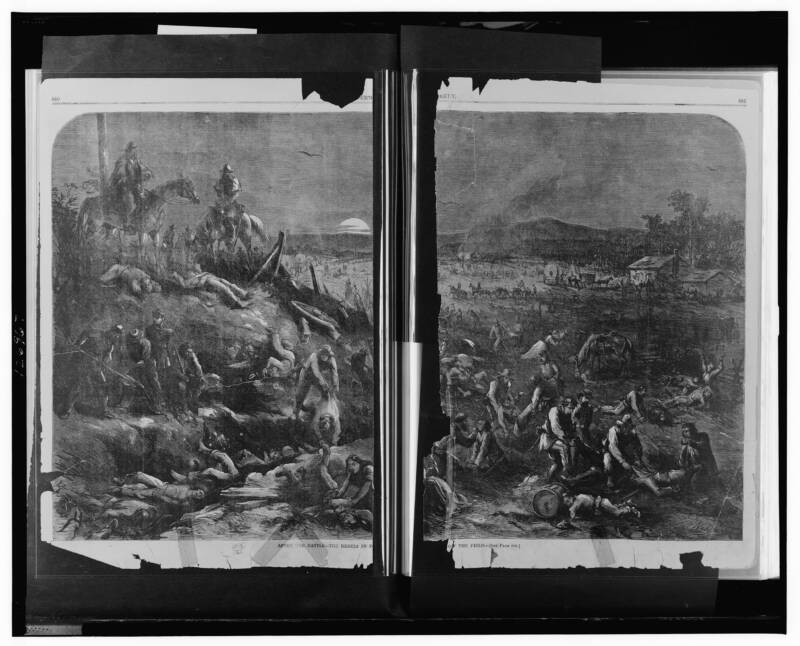

At first, Nast drew scenes from Civil War battles and other vignettes of war life. In one image, Nast sketched a wife kneeling and praying for her soldier husband, who was depicted gazing at pictures of his loved ones. In another, he showed the aftermath of the Union defeat at the Second Battle of Bull Run.

In this image below, Nast depicted the Confederates as dishonorable victors. According to thomasnast.com, his drawing — backed up by testimony from a New York Times reporter — showed how the Confederates had robbed the dead and thrown their bodies into trenches.

Thomas Nast/Public DomainOne of Thomas Nast's battle scenes. This one is entitled: "After the Battle — The Rebels in Possession of the Field."

And as time went on, Thomas Nast's cartoons became even more political.

How Thomas Nast's Cartoons Influenced U.S. Politics

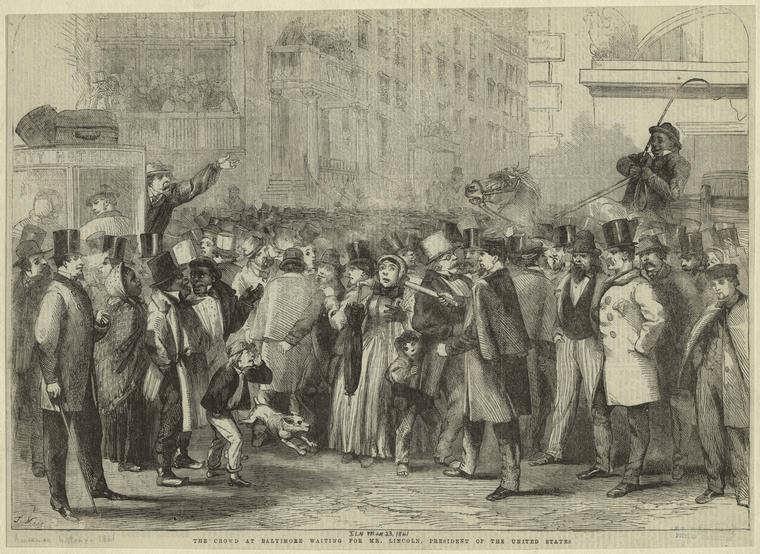

A strong supporter of Abraham Lincoln and the Union, Thomas Nast's cartoons in the 1860s frequently supported the president's policies.

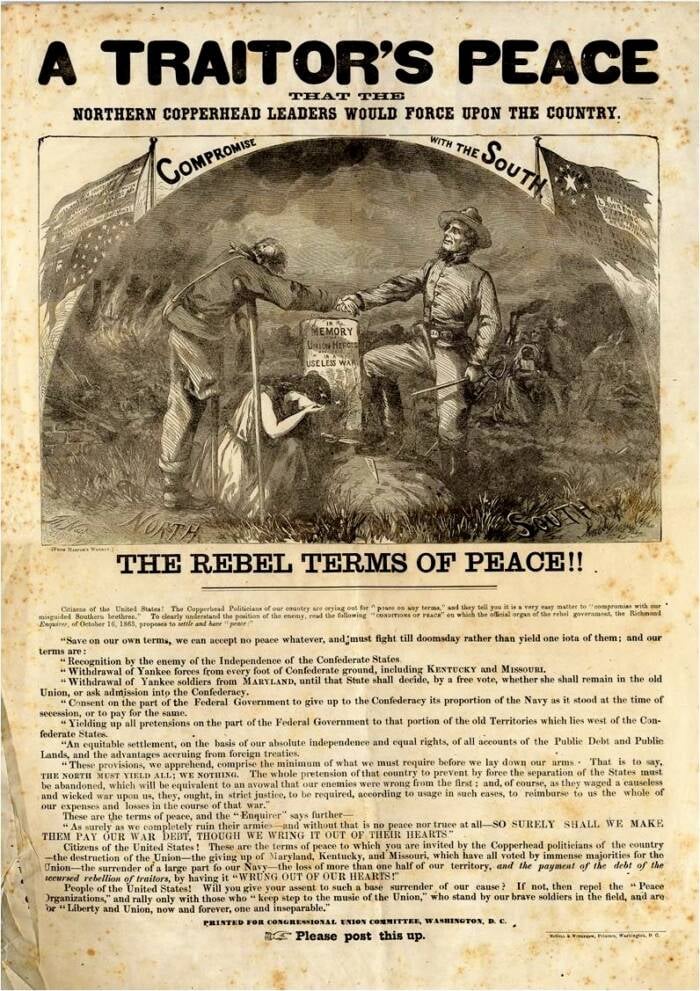

After Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation on Jan. 1, 1863, which freed enslaved people in Confederate states, Nast produced a cartoon showing the dark history of slavery alongside the hopeful future for freed Black Americans. When the Democrats nominated Union General George McClellan with the platform "Peace at Any Price," Nast published a scathing cartoon in September 1864 depicting Jefferson Davis standing on a Union soldier's grave that's marked by a stone engraved with the words: "In Memory of Our Union Heroes Who Fell in a Useless War."

Afterward, Lincoln's campaign team reprinted Thomas Nast's cartoon captioned with "A Traitor's Peace" and "The Rebel Terms of Peace!!"

Public DomainThe Lincoln campaign produced thousands of these pamphlets, which used Thomas Nast's cartoon to attack George McClellan.

Nast, Ulysses S. Grant once supposedly said, "did as much as any one man to preserve the Union and bring the war to an end." And Lincoln was quoted as saying: "Thomas Nast has been our best recruiting sergeant. His emblematic cartoons have never failed to arouse enthusiasm and patriotism, and have always seemed to come just when these articles were getting scarce."

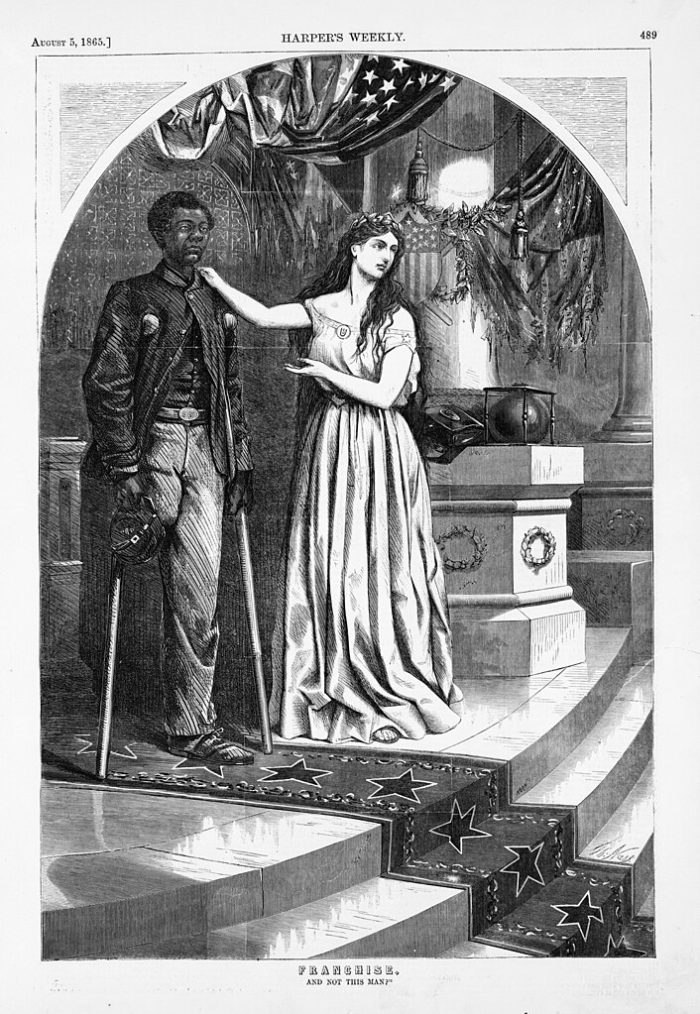

Thomas Nast's cartoons continued to confront politics after the Civil War. A supporter of Reconstruction and an antagonist to Lincoln's successor, Andrew Johnson, Nast frequently attacked Johnson's policies. Nast depicted Johnson as hapless and weak, and he didn't shy away from revealing the violent results of Johnson's inaction in the South, where newly freed Black Americans were vulnerable to attacks from white people.

In the 1870s, Nast would also turn his attention to the corruption of William "Boss" Tweed, the boss of the political machine Tammany Hall, and he drew especially scathing cartoons about Horace Greeley, the editor of the New-York Tribune who ran unsuccessfully against Grant in 1872.

"Nast, you more than any other man have won a prodigious victory for Grant," Mark Twain wrote to Nast in November 1872. "I mean, rather, for Civilization and Progress."

But Thomas Nast's cartoons did more than influence elections. They also changed how we talk about American politics — and culture.

How Thomas Nast's Cartoons Changed Politics And U.S. Culture

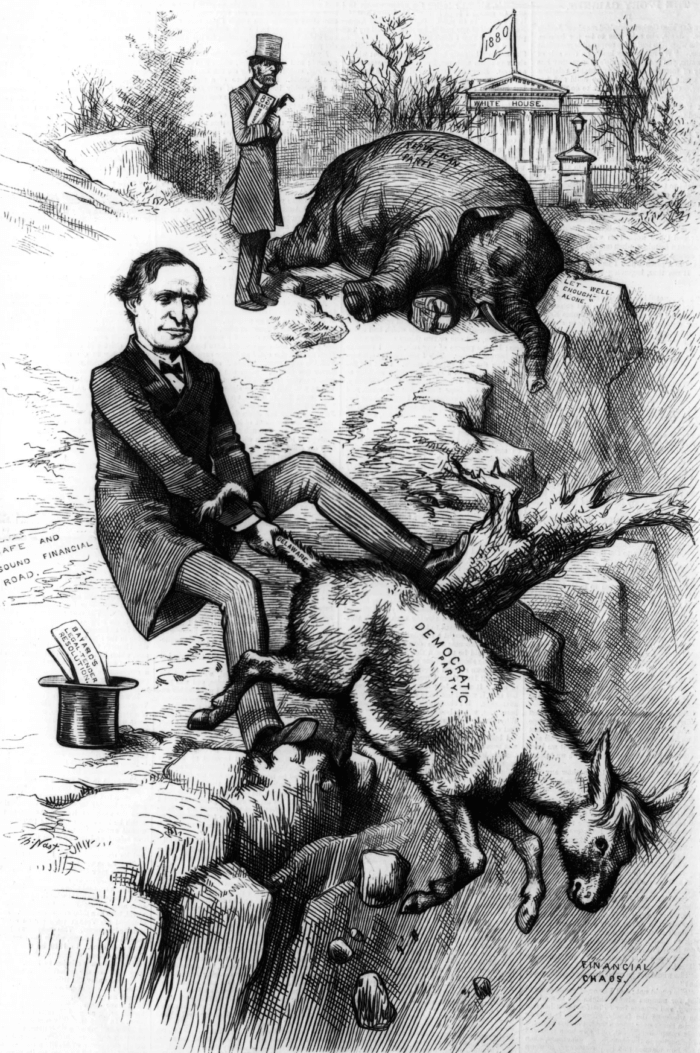

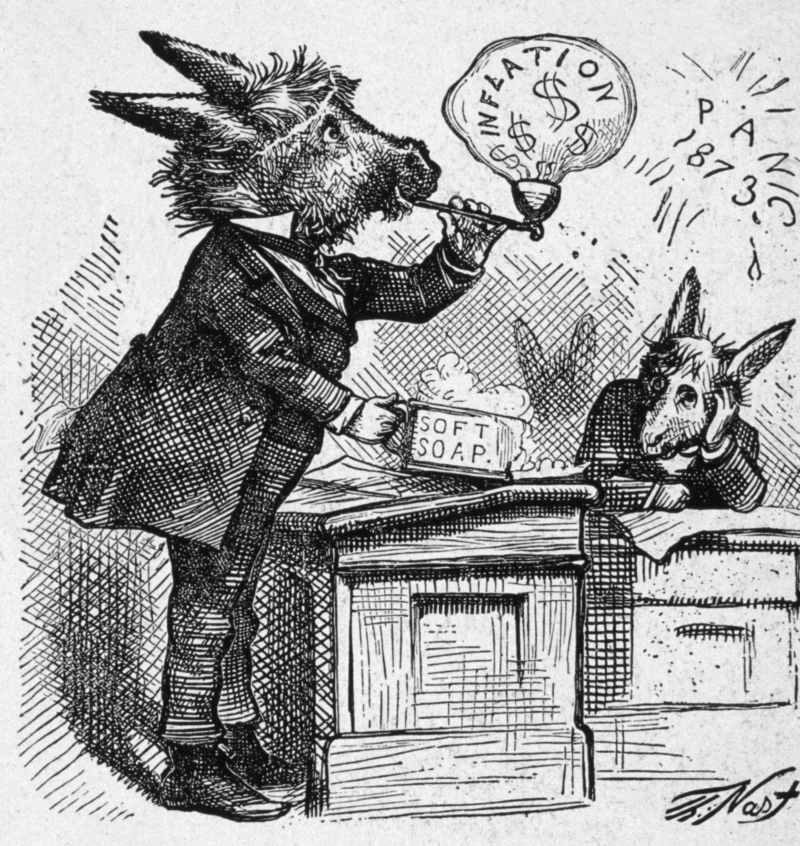

Today, Americans associate Democrats with donkeys and Republicans with elephants. And it's largely thanks to Thomas Nast's cartoons about U.S. politics that these symbols have endured.

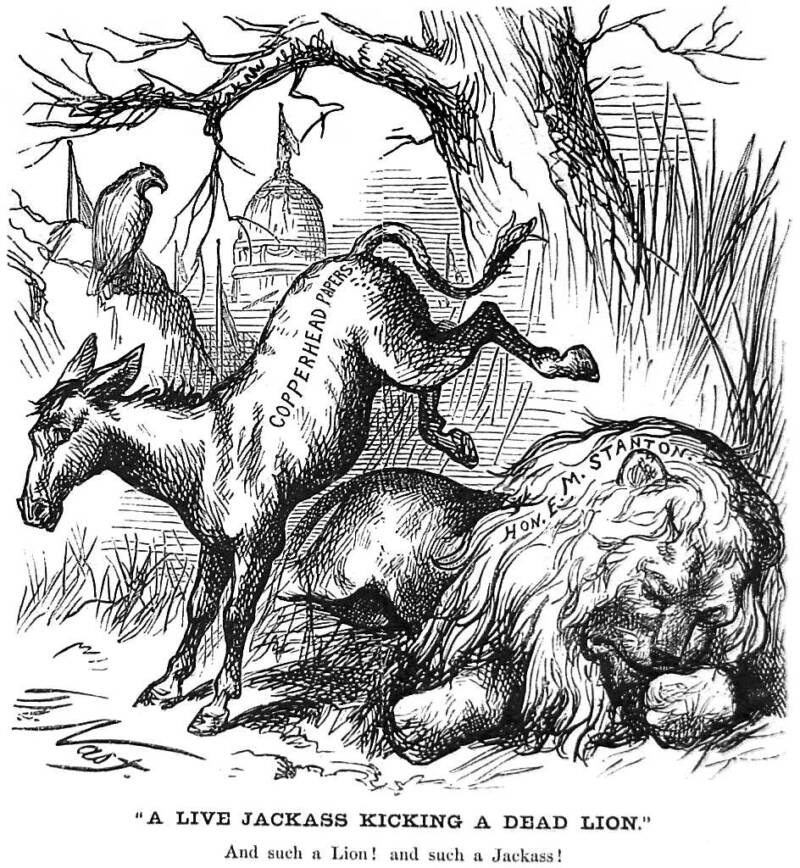

Public DomainA Copperhead (anti-war Democrat) as represented by a donkey, kicking over the lion body of U.S. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, who had just died.

Both predated Nash: The donkey had roots in the Andrew Jackson administration, and the Republican party had had the Civil War-era slogan "see the elephant," meaning "fight bravely." But Nast popularized these symbols. His cartoons mocked both parties, with an elephant representing the Republicans and a donkey representing the Democrats.

According to thomasnast.com, Harper's had a circulation of hundreds of thousands of people starting in the Civil War years. Each of Nast's cartoons reached between 500,000 and one million readers — and thus pushed the donkey and the elephant into the American political lexicon. But those weren't the only symbols that came to be associated with Nast.

Some were to be expected: Nast popularized depictions of Uncle Sam, for example, and Columbia, a female symbol he used to personify America. But he's also credited with creating our modern-day image of Santa Claus.

By the time Nast came along, Christmas had begun to take on some characteristics that modern audiences would recognize, including gifts, decorations, and Santa. Clement Clarke Moore's 1823 poem "A Visit from St. Nicholas" set a Christmas scene that described Santa Claus with a "round belly" that jiggled like a "bowlful of jelly."

Over 33 illustrations, Nast depicted Santa as rotund, bearded, and wearing red. But Nast was still a political cartoonist — and even his Santa Claus drawings often had an underlying political message. In an 1863 cartoon, for example, Santa is seen wearing Union stars and dangling a doll with a striking resemblance to Jefferson Davis.

But though Thomas Nast's cartoons were a mainstay of American life beginning in the 1860s, their era of dominance in the political and cultural sphere would come to an end by the 1880s.

The Downfall Of An American Political Cartoonist

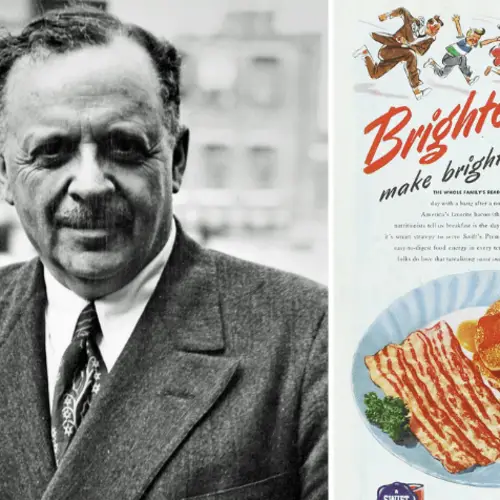

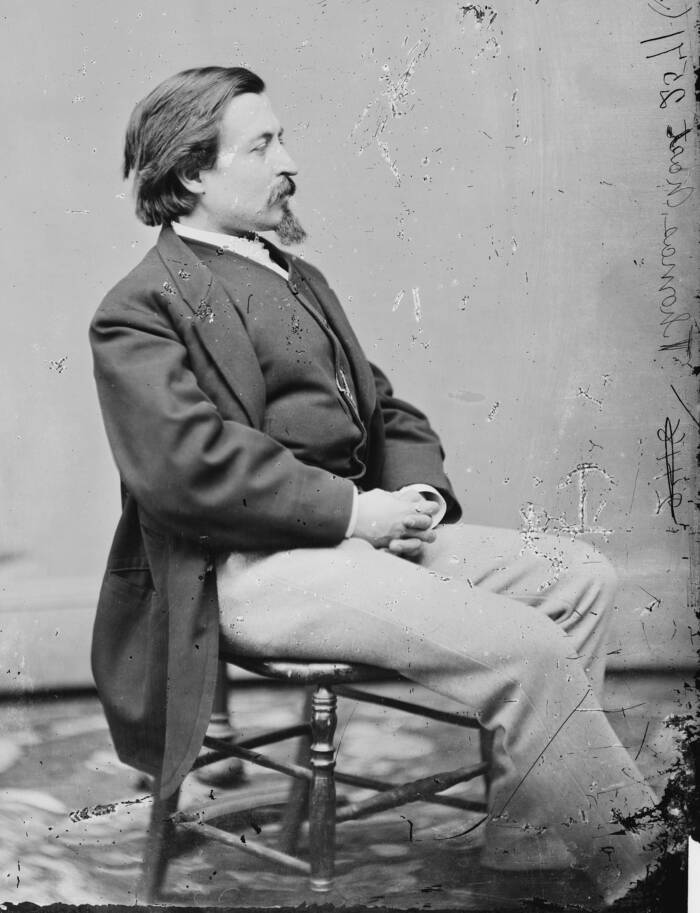

Public DomainThomas Nast photographed by Mathew Brady between 1860 and 1875.

In 1886, Nast and Harper's parted ways. It was the end of an era. Nast's cartoons had been popular for two decades — although their power had diminished — and Americans would no longer see Nast's depictions of Democratic donkeys, Tammany tigers, or pilloried politicians.

The rest of his life was difficult. Nast lost much of his fortune after making bad investments, and the weekly newspaper he started, Nast's Weekly, swiftly went out of business. Though Nast supported himself by painting and giving lectures, he was in dire financial straits until he received an offer of help from an unlikely ally: Theodore Roosevelt.

Roosevelt had long admired Nast, and, as reported in a 1971 issue of American Heritage, he wanted to do something to help. The president suggested that Nast become consul general in Ecuador. Nast wasn't especially thrilled by the offer, but he needed the money and decided to accept. Sadly, he died just a few months after his arrival from yellow fever, passing away on Dec. 7, 1902, at the age of 62.

In the end, Thomas Nast's cartoons would preserve his legacy for generations to come. In his drawings, Nast frequently mocked politicians and, just as often, expressed his support for Black suffrage and the rights of Native Americans and Chinese immigrants. His acerbic pen would both influence elections and introduce new cultural symbols into American life.

It's no wonder that Thomas Nast is known today as the father of the American political cartoon.

After reading about Thomas Nast's cartoons, discover the strange story of Wilmer McLean, who saw the Civil War begin in his front yard — and end in his parlor. Or, look through these haunting photos from the Battle of Gettysburg.