Challenger Deep lies 35,876 feet beneath the surface of the Pacific Ocean within the Mariana Trench, and the explorers who have ventured into its depths have spotted otherworldly landscapes, bizarre sea creatures, and even human trash.

During the Space Age of the 1960s, most of the world directed their gaze toward the heavens. But a select few were looking elsewhere — at the deepest part of the ocean, Challenger Deep.

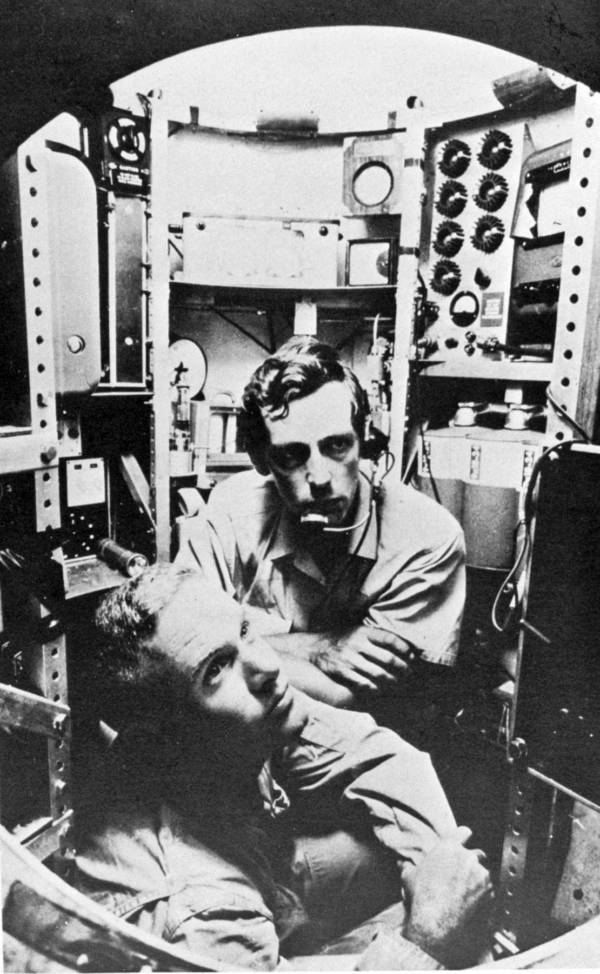

On Jan. 23, 1960, Swiss oceanographer Jacques Piccard and U.S. Navy Lieutenant Don Walsh visited Challenger Deep for the first time. Navigating from within a cramped, pressurized sphere, the two men sat huddled together, barely moving for nearly five hours as they made their descent to the Mariana Trench, some 200 miles southwest of Guam.

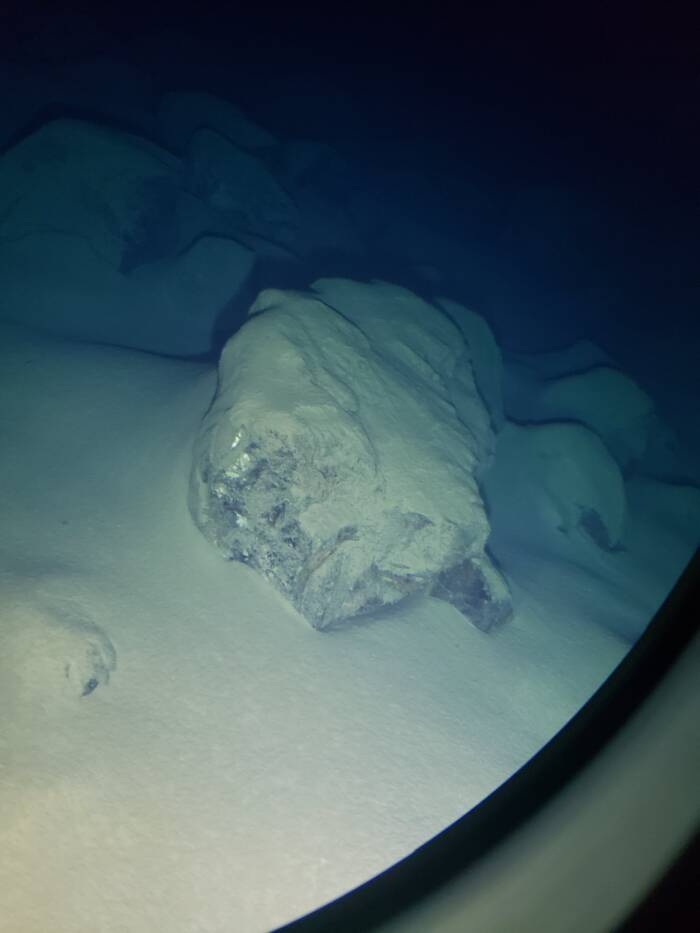

The watery world outside of their porthole was illuminated by a powerful beam, which soon became the only source of light as the Sun's rays and color evaporated during their slow descent. The eerie silence was penetrated only by conversation and, as Piccard later recalled, "crackling sounds, like ants in an ant hill, little cracking sounds coming from everywhere."

When they finally reached their destination, the two men held their breath and attempted to contact their team back at base using a specially-constructed communication device. They were unsure they would even succeed because no transmission of the type had ever been attempted before.

To their relief, a voice from the other end of the line replied: "I hear you weakly but clearly. Please repeat the depth." Walsh triumphantly responded, "Six three zero zero fathoms," or some seven miles below the surface of the sea. They had touched down on the deepest part of the ocean.

This is the story of Challenger Deep.

Challenger Deep, The Deepest Part Of The Ocean

Kmusser/Wikimedia CommonsThe Mariana Trench is located between Guam and the Mariana Islands, and Challenger Deep is its deepest point.

Challenger Deep is located at the southern end of the Mariana Trench, a 1,580-mile-long trench in the Pacific Ocean. It is the deepest ocean trench in the world, and Challenger Deep — at a breathtaking 35,876 feet below the surface of the water — is its deepest point. In other words, Challenger Deep is even deeper than Mount Everest is tall.

The ocean is divided into zones based on depth, starting with the epipelagic zone, or the sunlight zone. Challenger Deep is located at the deepest possible zone, the hadalpelagic, or simply hadal, zone, which is named after Hades, the Greek god of the Underworld.

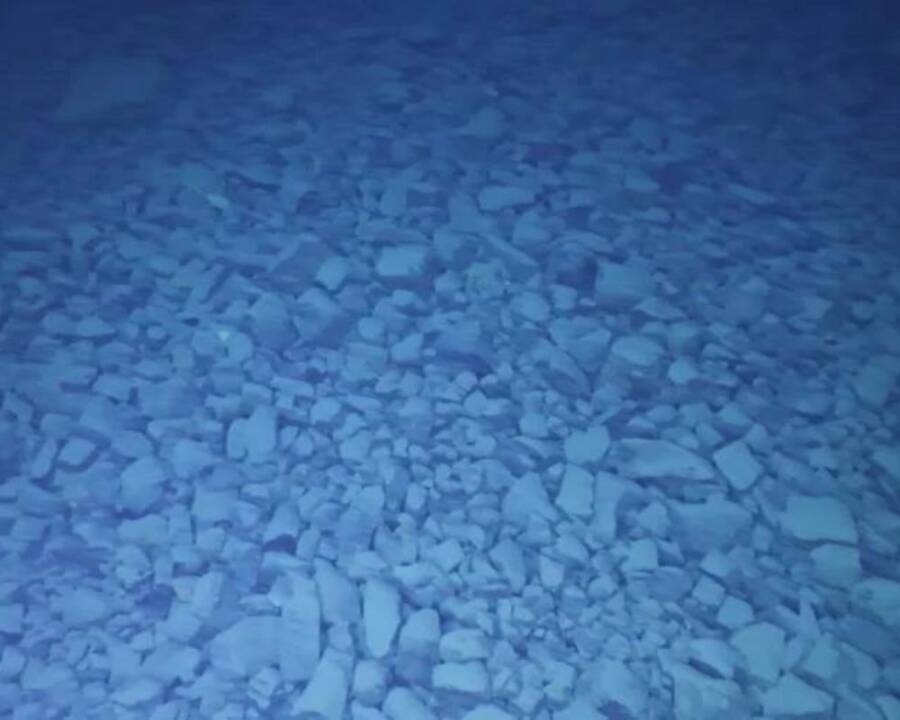

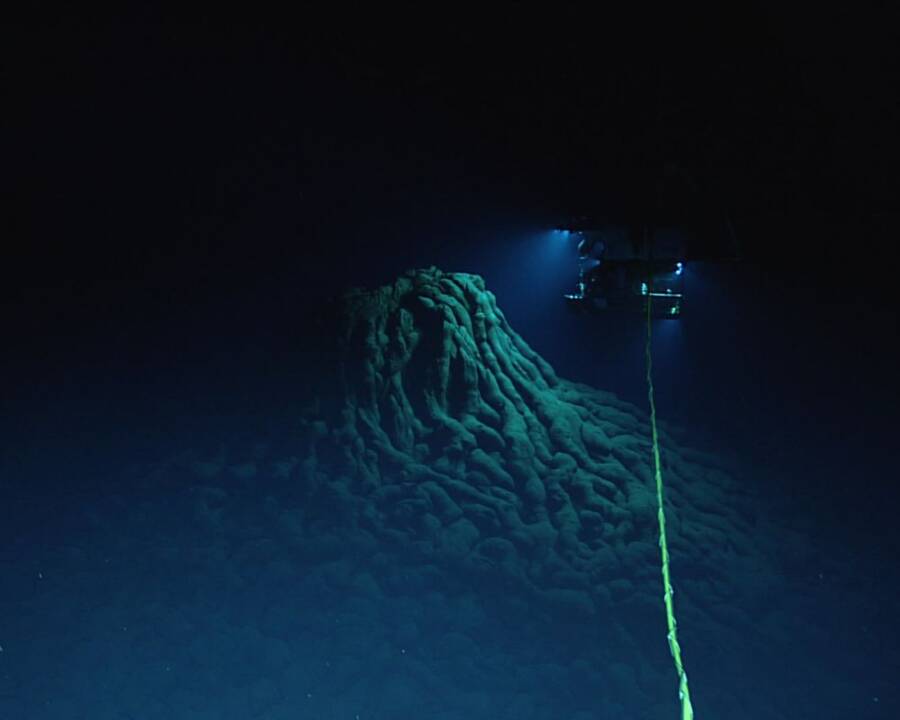

Challenger Deep is made up of three basins known as the Eastern, Central, and Western Pools, which are between 3.7 and 6.2 miles long. Here, there is no light. It's cold, with temperatures hovering just above freezing, and the pressure is more than 1,000 times that of the standard atmospheric pressure at sea level.

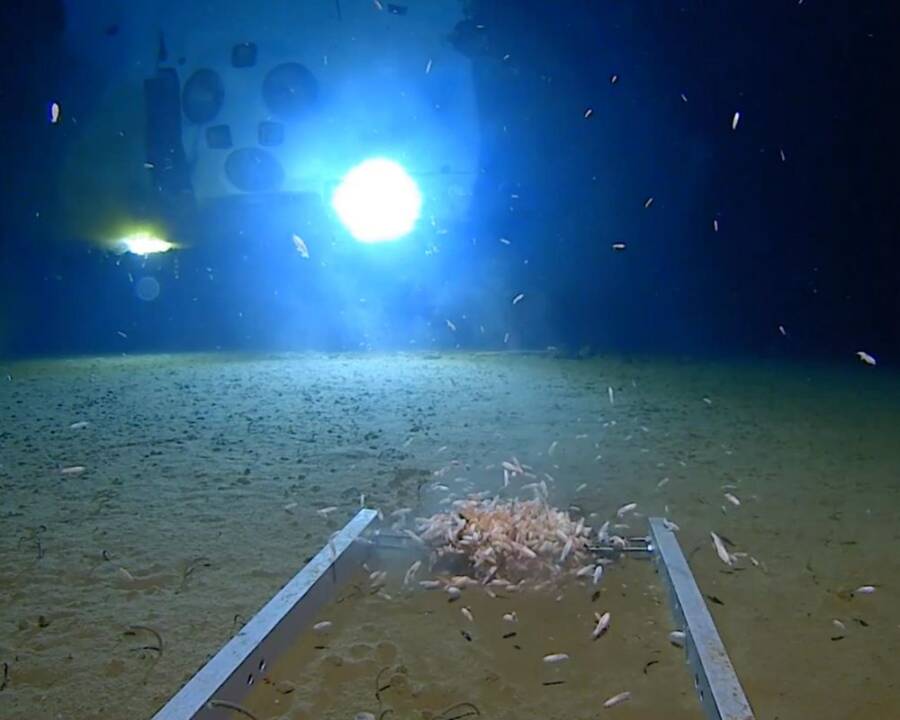

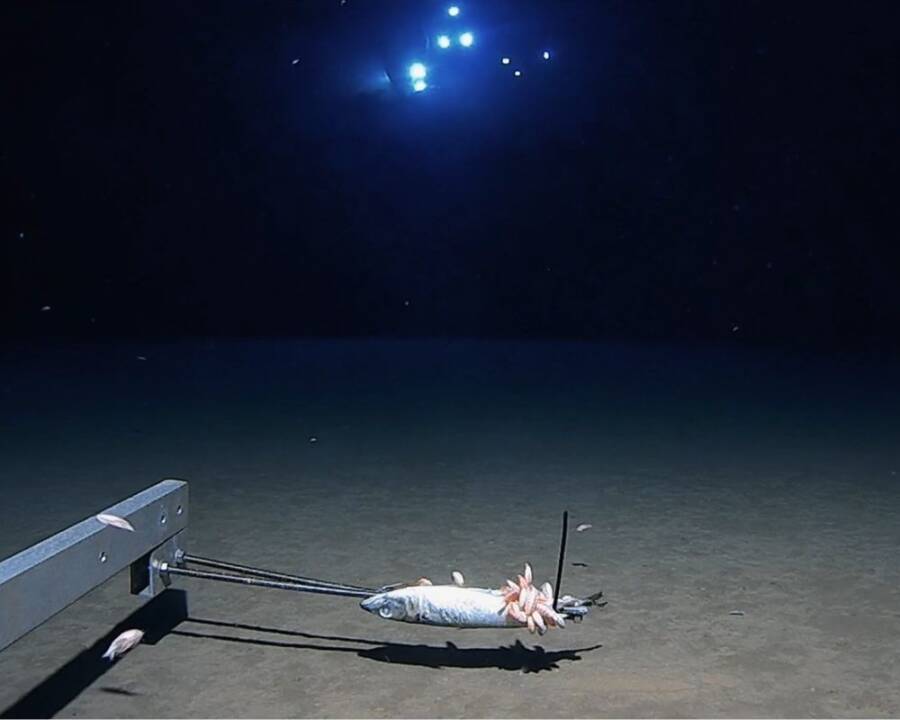

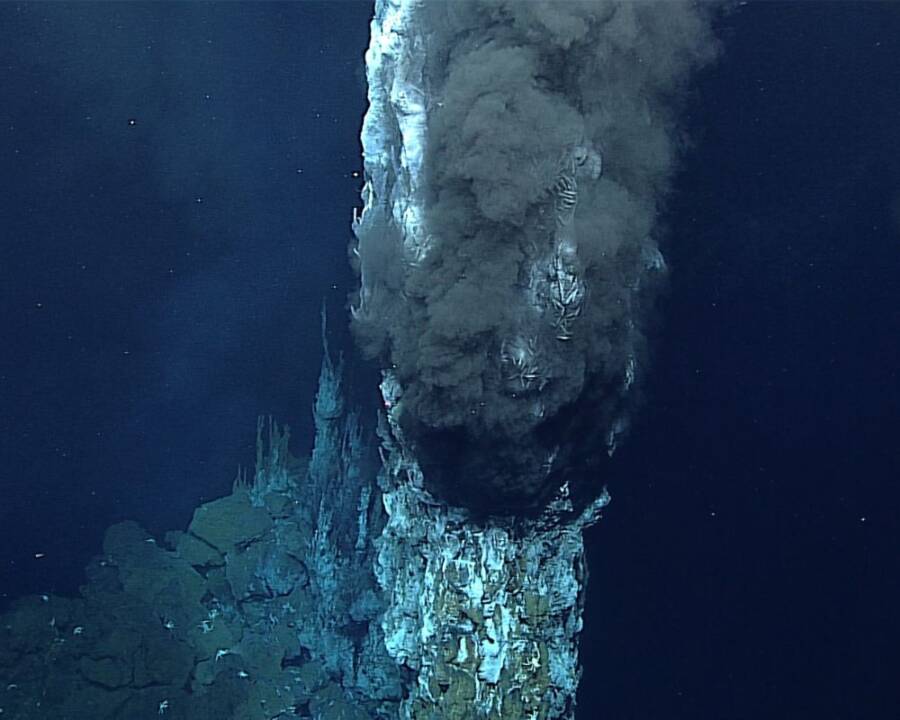

But though Hades oversaw a kingdom of the dead, scientists have found evidence of life in the deepest parts of the ocean. Scientific expeditions to Challenger Deep and the larger Mariana Trench have documented tiny creatures like plankton as well as sea cucumbers and sea fleas.

Census of Marine LifeScientists have documented sea cucumbers in Challenger Deep. This one, however, is from an expedition in the northern Gulf of Mexico.

Researchers are still learning about Challenger Deep to this day. However, exploration of the area began more than 100 years ago.

The Discovery Of Challenger Deep By The HMS 'Challenger'

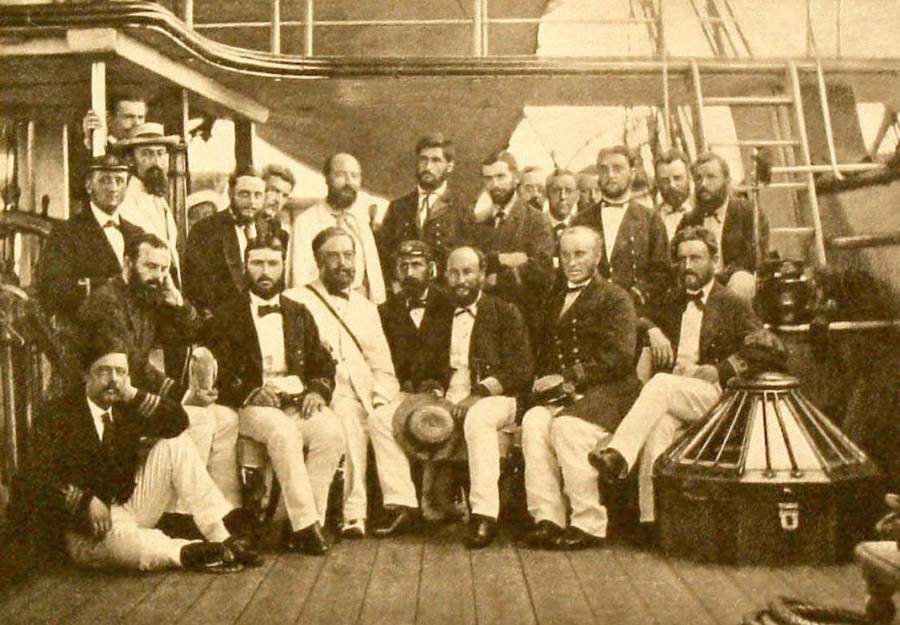

Public DomainThe crew of the 1872 Challenger Expedition, which was the first to explore the depths of the world's oceans and discover Challenger Deep, the deepest part of the ocean.

Although humans have been navigating the seas for thousands of years, "the reality is we know more about Mars than we know about the oceans," marine biologist Sylvia Earle explained to TIME in 1995. In fact, it was relatively recently that humans began to concern themselves with the depths of the ocean rather than just its surface.

Between 1872 and 1876, the Challenger Expedition set out to learn more about the ocean. According to the National Science Foundation website Dive and Discover, a British warship called the HMS Challenger was converted into a scientific vessel and set out at the end of 1872 to learn more about "ocean temperatures, seawater chemistry, currents, marine life, and the geology of the seafloor."

Led by naturalists John Murray and Charles Wyville Thompson, the Challenger carried samplers to gather mud and rocks, nets to capture animals at various depths, and, importantly, sounding lines that the crew could use to measure the depth of the water beneath the ship.

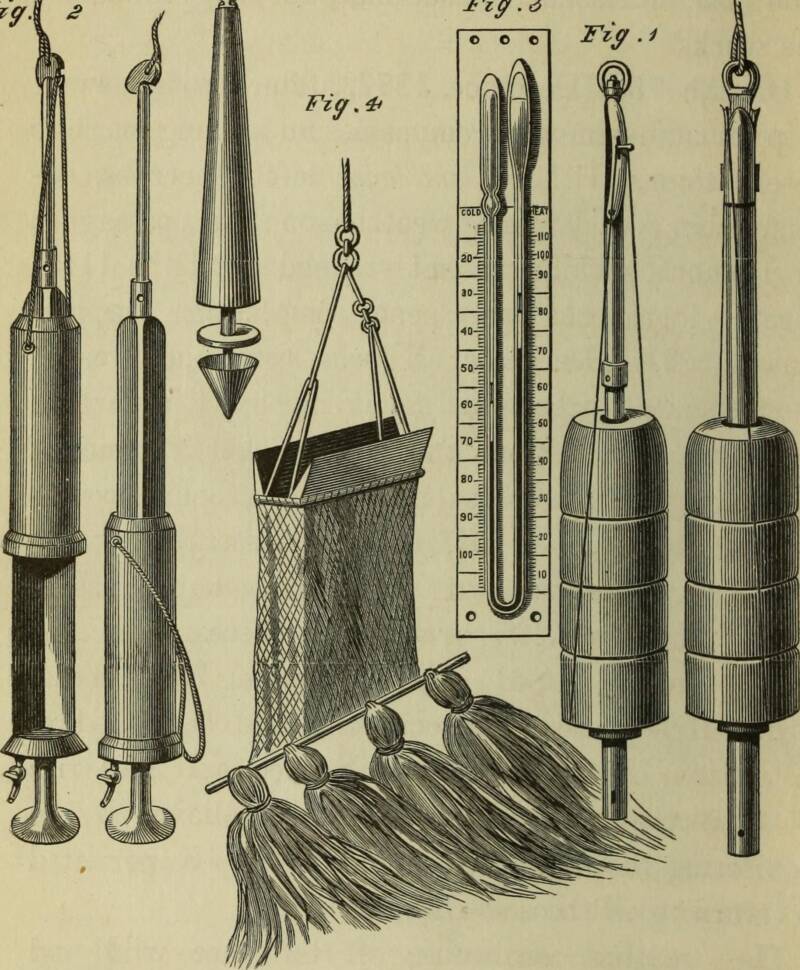

National Science FoundationSounding tools used by the Challenger Expedition to measure the depth of the ocean.

By the time the crew returned to England in 1876, they'd discovered some 4,700 new species of animals and plants — and had determined the deepest part of the ocean. In March 1875, the Challenger had been attempting to land at Guam when a storm blew the ship off track. While determining the next steps of their voyage, the crew decided to measure the ocean beneath them. They just happened to be floating above Challenger Deep, and their sounding equipment recorded a depth of 4,475 fathoms, or 26,850 feet.

In 1951, 75 years later, the HMS Challenger II returned to the same location. Thrillingly, the crew was able to confirm that the previous expedition had, in fact, located the deepest part of the ocean. Thomas Gaskell, the Chief Scientist on the Challenger II, later recalled the occasion in his book Under the Deep Oceans: Twentieth Century Voyages of Discovery.

The crew's sounding equipment had failed, so they instead tied a weight to a wire and dropped it off the side of the ship. "[I]t took from ten past five until twenty to seven, that is an hour and a half, for the iron weight to fall to the sea-bottom," Gaskell wrote. "It was almost dark by the time the weight struck, but great excitement greeted the reading." The Challenger II documented a depth of 35,394 feet.

Thus, Challenger Deep was named in honor of the two Challenger Expeditions.

"[I]t was not more than 50 miles from the spot where the nineteenth-century Challenger found her deepest depth," Gaskell later explained. "[A]nd it may be thought fitting that a ship with the name Challenger should put the seal on the work of that great pioneering expedition of oceanography."

Less than a decade later, human beings would attempt to explore Challenger Deep for the first time.

The First Mission Into Challenger Deep

It was one thing to measure Challenger Deep from the ocean's surface. It was quite another to descend more than 30,000 feet to the deepest part of the ocean. But that's what Swiss oceanographer Jacques Piccard and U.S. Navy Lieutenant Don Walsh resolved to do.

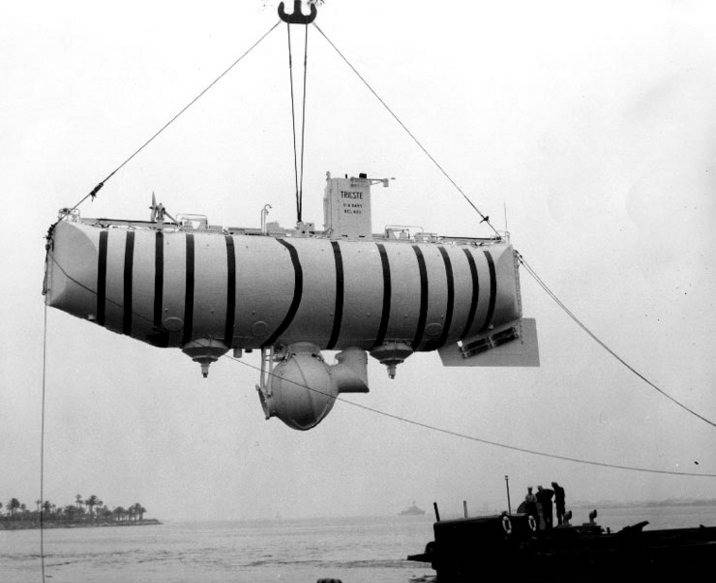

In a mission cloaked in secrecy — in case it failed — the two set out on Jan. 23, 1960, to explore Challenger Deep. They climbed into a 60-foot-long submersible called the Trieste, which Piccard and his father had designed for deep sea exploration, and began to descend.

U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command/Wikimedia CommonsThe Trieste, the vessel that Piccard and Walsh took to Challenger Deep.

"The buffeting waves, by covering the Trieste, have sent it into a region of eternal calm, an immense mysterious domain where the fish of the deeps open their avid eyes in the darkness, and where chilly waters are found only a few thousand feet from the eternally warm seas of the tropics," Piccard later recalled, according to a 1960 issue of National Geographic.

The descent took five nerve-wracking hours. Piccard wrote that the Trieste moved at the speed "of an elderly elevator" and that he and Walsh soon started observing phosphorescent plankton in the dark waters. Before long, they began to surpass the depths that they had explored in previous weeks.

Walsh murmured: "We are at a depth where no one has yet been."

And they still had some 10,000 feet to go.

As the two explorers neared the deepest part of the ocean, they heard a cracking sound and felt their vessel rock. Nothing else seemed to be wrong — they later determined the noise was a plastic window covering breaking, which posed no immediate danger — so Walsh and Piccard continued their descent.

Then, at 1:06 p.m., they reached Challenger Deep.

"[We had] made a perfect landing on a carpet of uniform ivory color, that the sea had laid down during the course of thousands of years," Piccard recalled.

He and Walsh stayed on the seafloor for about 20 minutes to make scientific observations. Then, they started back toward the surface. After a few hours, the sea turned from black to gray to blue. Finally, Piccard and Walsh emerged from the water — the first people to ever visit the deepest part of the ocean.

Public DomainWalsh and Piccard in their claustrophobic vessel.

"[W]e saluted gladly; not for posterity, to be sure, not for the photographers, but for the rediscovered Sun and pure air, even for the wind and the waves that submerged us each instant," Piccard wrote. "We had only one thought: profound gratitude for the success achieved, gratitude toward all those who had contributed to the success of this uncommon day."

Humans would not reach the floor of Challenger Deep again for over five decades. Although two unmanned submarines were sent on separate expeditions in 1995 and 2009 (one Japanese and one American), it was not until director James Cameron of Titanic fame carried out his own expedition that a manned vehicle would reach the bottom.

How Recent Explorers Have Studied The Deepest Part Of The Ocean

On March 26, 2012, James Cameron climbed into a submersible that he had co-designed and prepared to drop into Challenger Deep. In doing so, he became just the third person in history to reach the deepest part of the ocean and the first person to embark on a solo expedition.

"I've always dreamed of diving to the deepest place in the oceans," Cameron said according to National Geographic. "This quest was not driven by the need to set records, but by the same force that drives all science and exploration... curiosity."

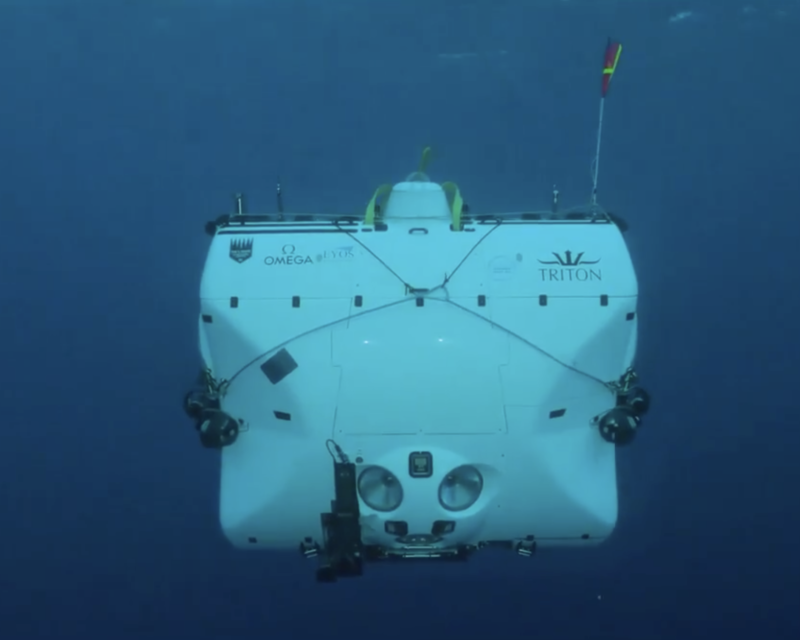

Richard Varcoe on behalf of Caladan Oceanic LLCVictor Vescovo's Limiting Factor has been used for a number of dives to Challenger Deep.

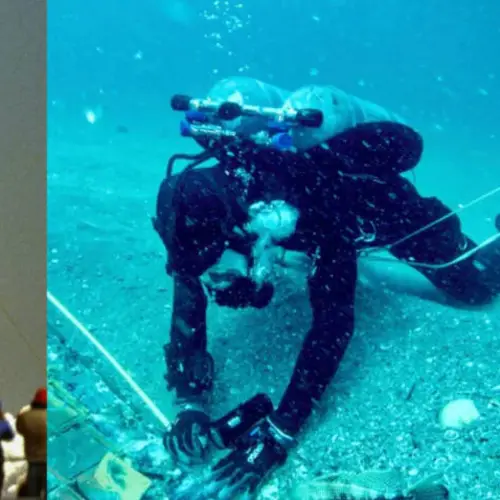

Unlike his predecessors, it only took the director about two-and-a-half hours to descend the nearly seven miles to Challenger Deep. Also in contrast to the previous manned expedition to Challenger Deep, Cameron's vessel was equipped with arms to take samples from the ocean floor, as well as 3D video cameras, which Cameron used to shoot footage for his 2014 documentary Deepsea Challenge.

But like Walsh and Piccard, Cameron experienced some harrowing moments during the descent. Because of the intense water pressure, several parts of his submersible started to malfunction.

"A couple of my batteries are dangerously low, my compass is glitching, and the sonar has died completely," Cameron wrote for National Geographic. "Plus, I've lost two of the three starboard thrusters, so the sub is sluggish and hard to control."

But despite these challenges, Cameron was able to spend three hours in Challenger Deep. He captured photos and videos and even documented 68 new species (most of which were bacteria) before returning to the surface.

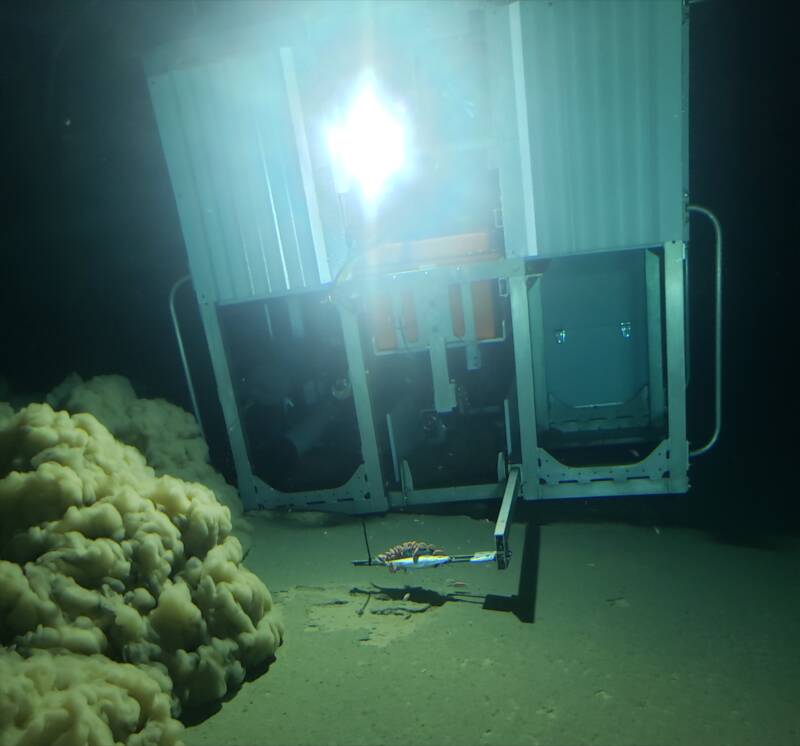

Since then, a number of other people have also been able to make the dive to the deepest part of the ocean. In 2019, investor and explorer Victor Vescovo — who has also climbed Mount Everest — descended to Challenger Deep in the submersible he'd commissioned, Limiting Factor. This submersible was also used in a number of subsequent missions.

Victor Vescovo/Wikimedia CommonsVictor Vescovo and Dr. Dawn Wright inside the Limiting Factor during an expedition to Challenger Deep's Western Pool in July 2022.

In June 2020, Victor Vescovo ventured into Challenger Deep with Kathryn Sullivan, the first American woman to walk in space. Upon returning from her voyage to the deepest part of the ocean, Sullivan earned the moniker "The Most Vertical Girl in the World."

Thus, the number of people who have visited Challenger Deep continues to grow. To date, more than two dozen explorers have descended into the depths of the ocean. They've documented the strange, alien-like landscape and, sadly, bits of trash that have floated down.

There's undoubtedly still more to learn about Challenger Deep, the deepest part of the ocean. Perhaps one day it will be more accessible for regular people and not just explorers. Until then, satiate your curiosity by looking through the collection of photos in the gallery above.

After this look inside Challenger Deep, the deepest part of the ocean, check out some of the strangest deep sea creatures ever found. Then, read about the prehistoric fish known as the Coelacanth, which scientists thought had gone extinct millions of years ago.