Learn the history behind the trial of the Chicago 7 and how defendants like Abbie Hoffman and Bobby Seale protested the Vietnam War during the 1968 Democratic National Convention.

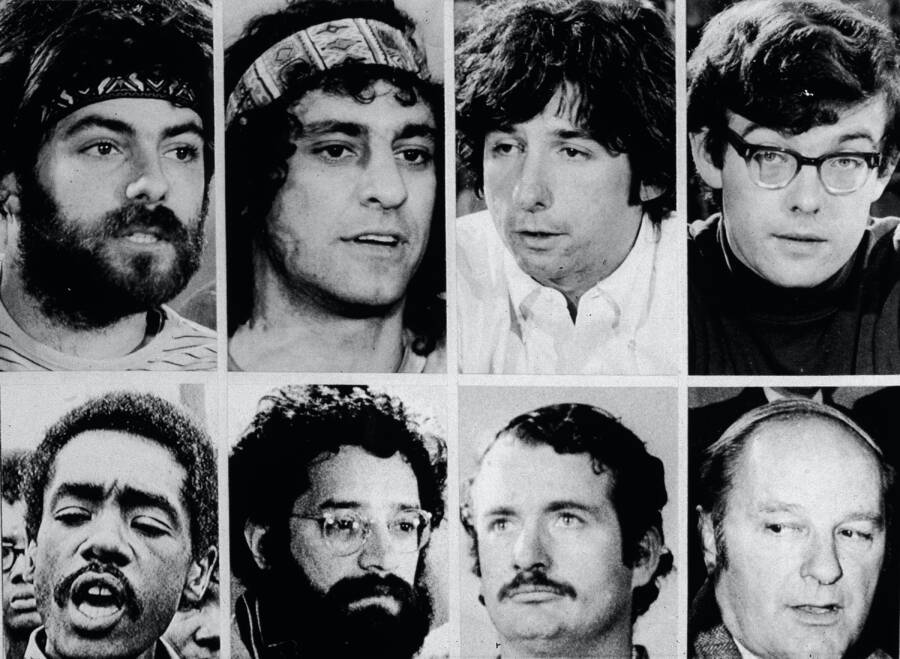

Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesThe original Chicago Eight: Jerry Rubin, Abbie Hoffman, Tom Hayden, Rennie Davis, Bobby Seale, Lee Weiner, John Froines, and David Dellinger.

The historic trial of the Chicago Seven saw prominent antiwar activists charged with conspiracy to incite a riot while crossing state lines. The riot in question took place outside the 1968 Democratic National Convention — and it happened during an incredibly tense time in American history.

In the midst of the Vietnam War, a generation of youths rose up in protest against America’s involvement in the overseas battle. So there was increasing pressure on the establishment to calm this outrage.

With President Lyndon Johnson deciding not to run for re-election, the Democratic Party was trying to select a new candidate at the convention. But many activists demanded that this candidate should be antiwar — and protested the convention in Chicago to make their voices heard.

The ensuing demonstrations at the International Amphitheater quickly turned violent — and eight activist figureheads were later blamed.

Originally known as the Chicago Eight, the defendants hit with conspiracy charges included famous figures like Black Panther Party cofounder Bobby Seale, Abbie Hoffman, and Tom Hayden. But Seale would eventually be tried separately from his fellow activists, leaving them as the Chicago Seven.

As Aaron Sorkin’s Netflix movie The Trial of the Chicago 7 shows, this trial was quite a dramatic one. And not all the defendants had a happy ending.

The Chicago Seven And 1960s Antiwar Activism

Charles H. Phillips/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty ImagesActivists forming a circle around the statue of Union General John A. Logan during the 1968 DNC protests.

In order to understand the magnitude of political activism in 1960s America, it’s imperative to grasp the historical context of the times.

President John F. Kennedy had been assassinated in 1963. Civil rights leaders like Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. had also met an unfortunate fate, in 1965 and 1968, respectively. So the Vietnam War was further disrupting a nation that was already grieving huge losses.

In 1966, Bobby Seale had cofounded the Black Panther Party to form a political organization that protected African Americans from police brutality and other forms of injustice in the country. But it didn’t take long for the Vietnam War to impact marginalized communities as well.

The Chicago Eight activists were shocked that the government demanded support for military interventions while some government officials were terrorizing impoverished communities in America at the same exact time. For Youth International Party (YIP) founder Abbie Hoffman and his peer Jerry Rubin, pointing this out was vital to their movement.

After all, YIP had been founded as a loose group of anarchists, artists, and societal dropouts who embraced theatricality to “stick it to the man.” So it made sense why they’d protest the war – and the powers who gave it the green light in the first place.

Meanwhile, David Dellinger, chairman of the National Mobilization Committee to End War in Vietnam (MOBE), and Tom Hayden, who led the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) with Rennie Davis, were all just as inspired to mobilize a protest. With activist John Froines and teacher Lee Weiner rounding out the crew, the planning began.

Many of these antiwar leaders met in Lake Villa, Illinois on March 23, 1968, and coordinated their prospective plans with more than 100 likeminded activist groups. Rubin aimed to bring together 100,000 people as part of a Yippie Youth Festival — and forged ahead despite being denied a permit.

The Perfect Storm

On March 31, when President Johnson announced he wouldn’t seek reelection, a big antiwar protest seemed unnecessary at first. But then, Vice President Hubert Humphrey entered the race. Not only did Humphrey embrace many of Johnson’s policies, he was also seen as the leading spokesman for U.S. war policy in Vietnam.

April was already a tense month. Riots followed Martin Luther King’s assassination, during which Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley reportedly gave a “shoot to kill” order to the police. And in June, presidential candidate Robert Kennedy was also assassinated — just after he won a primary in California.

By August, there had already been months of discontent all across the nation — especially in Chicago. To make matters worse, a telephone strike in the Windy City was expected to complicate convention efforts.

Anticipating more unruly protests outside the convention, many Democrats wanted to move the three-day event to Miami.

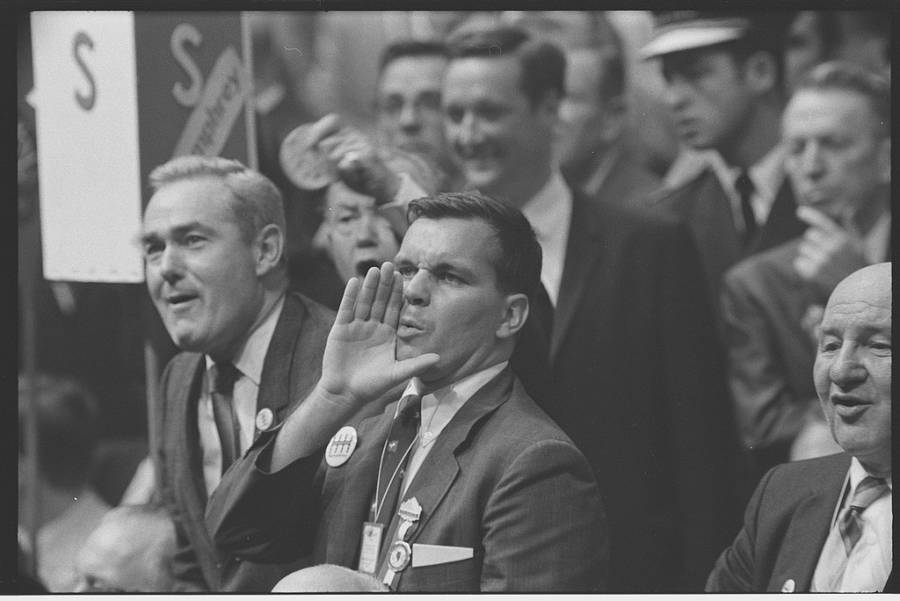

Warren K. Leffler/Library of CongressIllinois delegates booing Senator Abraham Ribicoff for criticizing the violent Chicago police tactics being employed outside. Aug. 28, 1968.

Even the television networks were in agreement with this, as the phone strike limited their camera setups to the hotels and the convention center. Anything shot elsewhere would have to be captured on film and then processed before it was aired.

Nonetheless, Chicago Mayor Daley was adamant that his city was ready — and vowed to withdraw his vote for Humphrey if the apparent nominee called for relocating the event. Meanwhile, President Johnson agreed, and reportedly said, “Miami is not an American city.”

The 1968 Democratic National Convention

With the convention underway between August 26th and August 29th, Humphrey was sitting pretty with between 100 and 200 more delegates than he needed to win. Nonetheless, antiwar pressure from within the Democratic Party and outside the International Amphitheater started to grow.

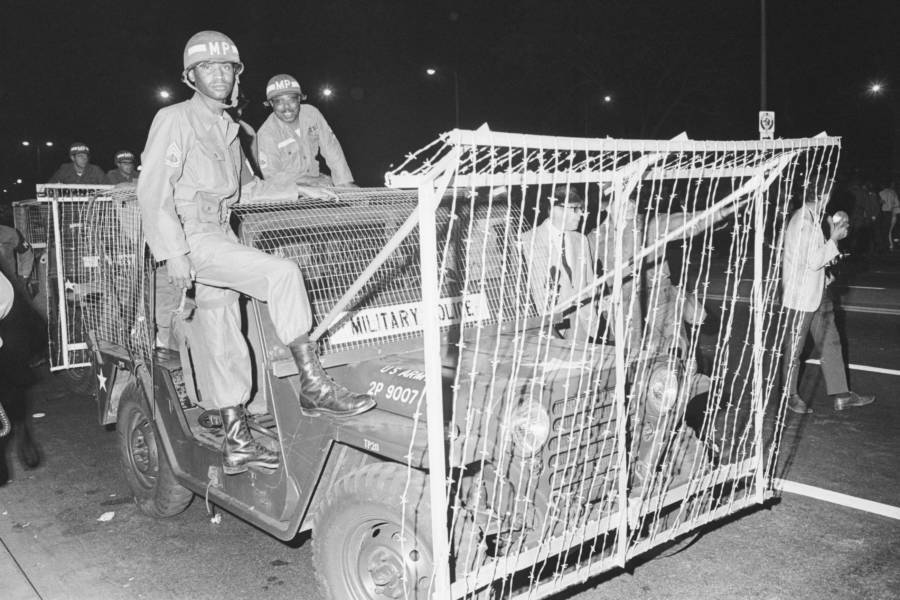

Bettmann/Getty ImagesNational Guardsmen atop their riot vehicle across from the convention center.

The violence first began on Aug. 25, 1968. Undeterred by rejected permits to demonstrate outside the amphitheater, protesters forged ahead to make their voices heard anyway. They were met with colossal pushback from 11,900 Chicago cops, 7,500 U.S. Army troops, 7,500 Illinois National Guardsmen, and 1,000 Secret Service agents over the course of five days.

The worst day of rioting during this period was August 28th, which would come to be known as the “Battle of Michigan Avenue.” Not only were many protesters beaten by the police, innocent bystanders, reporters, and doctors offering medical assistance were attacked as well. Countless people were injured. Meanwhile, hundreds of demonstrators were arrested, with estimates ranging from 589 to over 650.

“The notion that anybody came to the party with the idea of a big fight is wrong,” said SDS head of security Marilyn Katz. “I understand that they felt that one, they should keep control of their city, and that the Democratic Party and the mayor were saying, ‘We’re counting on you to keep things in order.’ There was no excuse for beating us.”

Charles H. Phillips/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty ImagesPolice beating protesters in Grant Park in August 1968.

While Humphrey chose Senator Edmund Muskie to be his running mate, the ticket later lost to Republicans Richard Nixon and Spiro Agnew. As their administration refused to immediately withdraw troops from Vietnam, the Chicago Eight activists were embroiled in an infamous court battle.

The Trial Of The Chicago Seven

Amidst the tear gas and police batons beating down protesters and journalists alike were the Chicago Seven figureheads giving speeches in the city. Widely covered by the media, these riots had serious consequences.

On March 20, 1969, eight police officers and eight civilians were indicted by a Chicago grand jury in connection with the violence. And unfortunately for the Chicago Seven (originally the Chicago Eight), provisions of the 1968 Civil Rights Act had made crossing state lines to incite a riot a federal crime.

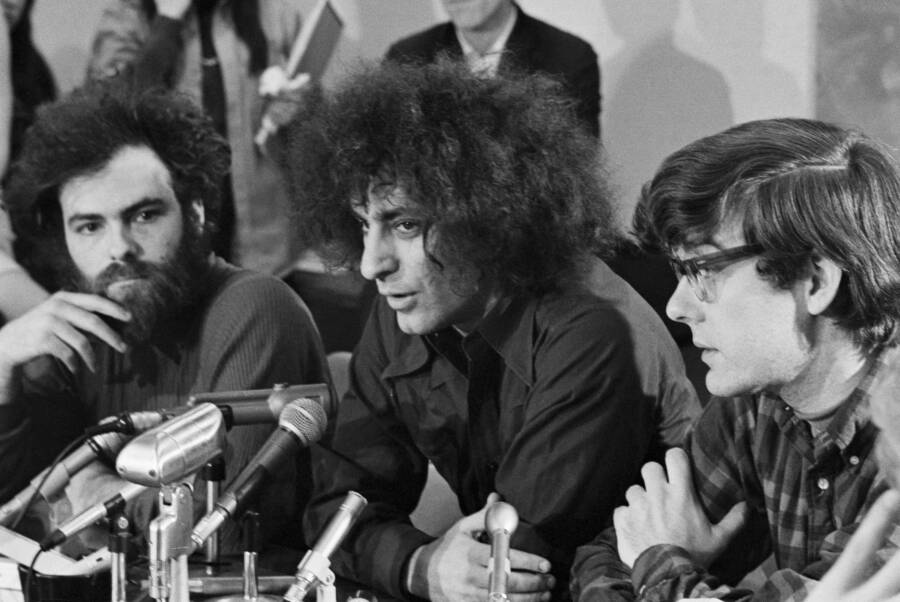

Bettmann/Getty ImagesJerry Rubin, Abbie Hoffman, and Rennie Davis address reporters amidst their trial.

Dellinger was a clear target as head of MOBE, as were Davis and Hayden as key figures of the SDS. Meanwhile, Hoffman and Rubin’s YIP members comprised a large chunk of the demonstrators involved. Having participated, Weiner and Froines were charged as well.

But for Bobby Seale — who had only agreed to join the demonstrations as a last-minute replacement for another Panther — being charged on the pretext of conspiracy seemed preposterous to him. Nonetheless, the trial of the Chicago Eight began on Sept. 24, 1969.

The trial, presided over by Judge Julius Hoffman, was routinely mocked by its defendants. On one occasion, Jerry Rubin and Abbie Hoffman wore judicial robes to court, prompting Judge Hoffman to order them removed. They took them off, only to reveal Chicago police uniforms underneath.

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty ImagesHayden in the thick of protests in Chicago’s Lincoln Park during the Democratic National Convention. August 1968.

“We came to Chicago in August 1968 to disrupt the ritual and sham which is ordinarily put over as the democratic process,” said defendant Rennie Davis. “Now we are disrupting the ritual and sham which Judge Hoffman calls the judicial process.”

Abbie Hoffman called the judge “Julie,” raised his middle finger while being sworn in, and said that the judge’s idea of justice was the only obscenity in the courtroom. To the defendant’s point, the judge routinely interrupted the men on trial as well as their attorneys, while claiming that he was being patient.

“You haven’t been patient at all,” argued Rubin. “You interrupted my lawyer right in the middle of his argument… I’ll ask you to remain quiet while my attorney presents his argument.”

The Passion Of Bobby Seale

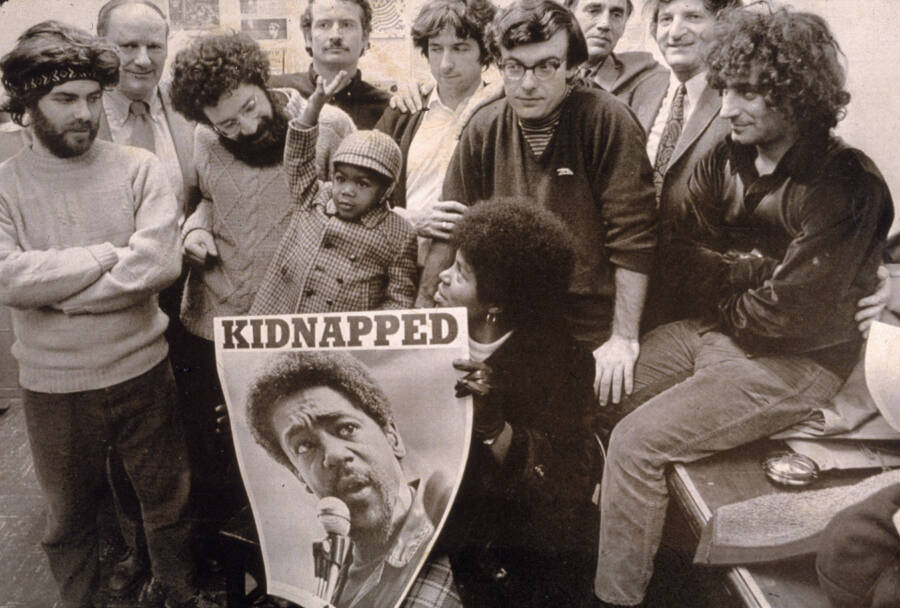

New York Times/Getty ImagesThe Chicago Seven pose with a poster of Bobby Seale, whose trial had just been separated from theirs. October 1969.

For Seale, the proceedings were not only unwarranted but seemed have underlying motives.

As cofounder of the Black Panther Party and a target of the FBI’s subversive COINTELPRO program, his perspective was certainly not unfounded. Nonetheless, his outbursts at the beginning of the trial created quite a stir.

“You have did everything you could with those jive lying witnesses up there presented by these pig agents of the government to lie and say and condone some rotten racists, fascist crap by racist cops and pigs that beat people’s heads — and I demand my constitutional rights,” Seale shouted.

Judge Hoffman was unable to silence the defendant — and so he ordered Seale to be bound, gagged, and chained to his chair on Oct. 29, 1969.

As Seale sat squirming and attempting to speak through the gag placed tightly around his mouth, defense attorney William Kunstler said, “This is no longer a court of order, Your Honor, this is a medieval torture chamber.”

Soon after, Seale — the only Black defendant in the group — was separated from his fellow white defendants and ordered to stand trial on his own. Before long, Seale was sentenced to 48 months in prison for 16 acts of contempt. However, his contempt charges would later be dismissed.

What Happened To The Rest Of The Defendants?

David Fenton/Getty ImagesThe Chicago Seven and their lawyers outside the courthouse.

“You’re the laughing stock of the world,” Rubin told the judge. “Every kid in the world hates you because they know what you represent. You are synonymous with Adolf Hitler. Adolf Hitler equals Julius Hitler.”

Defense attorney William Kunstler often spoke up about the mistreatment of the defendants throughout the trial, and called the proceedings a “legal lynching,” for which the judge was “wholly responsible.”

Ultimately, the case went to the jury on Feb. 14, 1970 — with the judge convicting all seven of their charges. Kunstler and another defense attorney, Leonard Weinglass, were also convicted of contempt for their remarks.

However, the jury’s returned verdicts on Feb. 18, 1970 saw Froines and Weiner acquitted of all charges. But Dellinger, Davis, Hayden, Hoffman, and Ruben weren’t quite as lucky.

Though acquitted of conspiracy, the remaining defendants were found guilty of intent to riot. They were sentenced to five years in prison and fined $5,000.

However, none of the seven served time since a Court of Appeal overturned the criminal convictions in 1972. Most of the contempt charges were eventually dropped as well.

The Aftermath And Chicago Seven Legacy

Bobby Seale and his Chicago Seven peers weathered a highly flawed trial that saw the Black Panther Party cofounder thrown in prison. Unsurprisingly, this only reinforced anti-establishment fervor among the youth. This outrage continued even after defendants saw their convictions overturned.

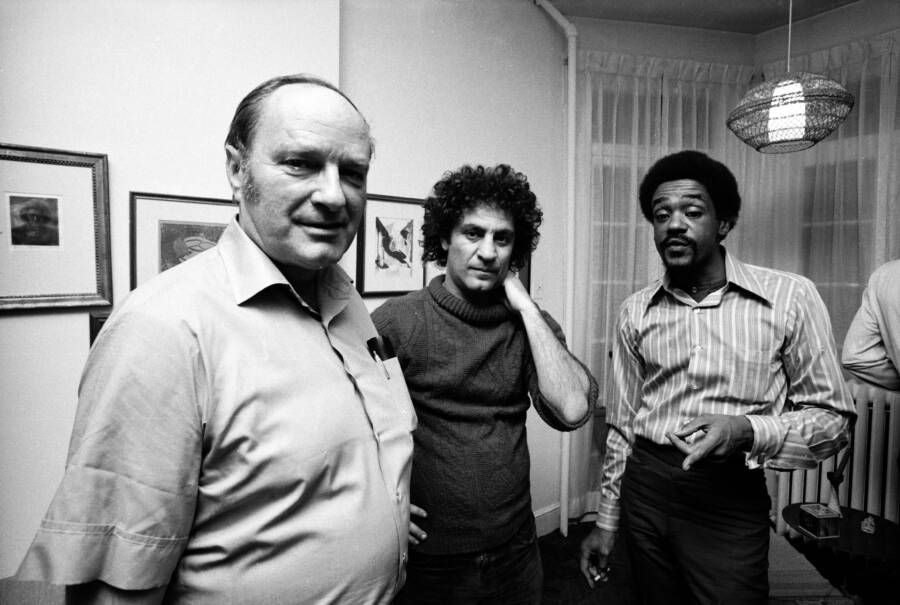

John Olson/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty ImagesDavid Dellinger, Abbie Hoffman, and Black Panther cofounder Bobby Seale at Seale’s birthday party in New York.

The Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals based its 1972 decision on the grounds that Judge Hoffman improperly limited the voir dire of the defendants.

What’s more, Judge Hoffman had also clearly expressed his open bias against the Chicago Seven. The appeals court also found that authorities had bugged the phones of the defendants’ counsel.

The voiding of these convictions allowed the Chicago Seven to get back to work and rise to even greater heights. While Hoffman tragically committed suicide in the 1980s, he authored numerous books and continued his mission to inspire the youth to fight for their rights until his death.

Hayden later became a California assemblyman and state senator, while Seale recounts his experience as an activist and Black Panther to this day.

In the end, the true story of the Chicago Seven is so remarkable that it almost appears fictional. With Aaron Sorkin’s The Trial of the Chicago 7 mining the events from the past, it’s clear that this moment in history remains just as shocking and thought-provoking 50 years after the fact.

After learning about the true story behind ‘The Trial of the Chicago 7,’ take a look at 66 photos from the 1960s. Then, relive the civil rights movement through 55 powerful photos.