Named for French inventor Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre, the daguerreotype was the world's first successful form of photography — and it captured historic images of everyone from Abraham Lincoln to Emily Dickinson to real-life samurai.

It’s easy to take the conveniences of modern-day photography for granted. Less than 20 years ago, the first iPhone had a single, two-megapixel camera on the back. Now, many of the latest smartphones boast multiple lenses, with the main camera capturing detailed images at a staggering 48 megapixels, or sometimes even higher.

Consumer camera technology has progressed at an increasingly rapid rate — so fast that it’s difficult to remember how cumbersome the photography process used to be. What now fits in your pocket once required a large box, careful lighting, a patient subject, and a lengthy development time.

While cameras may seem like a relatively recent innovation, the history of photography goes back much further than you’d think. The first Kodak camera emerged in 1888, but decades before that, the world was introduced to early photographs known as daguerreotypes.

How The Daguerreotype Was Created

Inventors had been trying to create something similar to the modern camera for years before one would ever pop into existence, but it can safely be said that the invention of photography officially emerged in 1826.

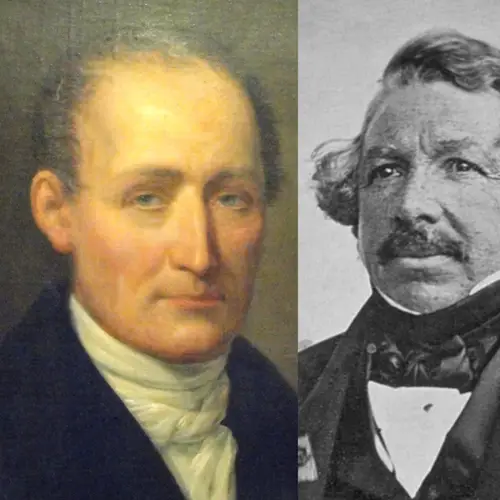

It was this year that a Frenchman named Joseph Nicéphore Niépce created the first permanent photographic image via a process known as "heliography," which involved bitumen of Judea (a type of asphalt) on a pewter plate. However, heliography required prolonged exposure times that lasted several hours, making it impractical for widespread use.

Then, in 1829, Niépce entered into a partnership with the scientist and artist Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre, and the two worked to refine Niépce's techniques, eventually narrowing down the exposure time to just 15 minutes. Niépce unfortunately died in 1833, but Daguerre continued their collaborative efforts, ultimately developing the daguerreotype process by 1839.

While nowhere near as simple as the point-and-click nature of today's cameras, the process ended up being exactly what Daguerre needed to skyrocket photography to international acclaim.

The Daguerreotype Process Revolutionized The Early Years Of Photography

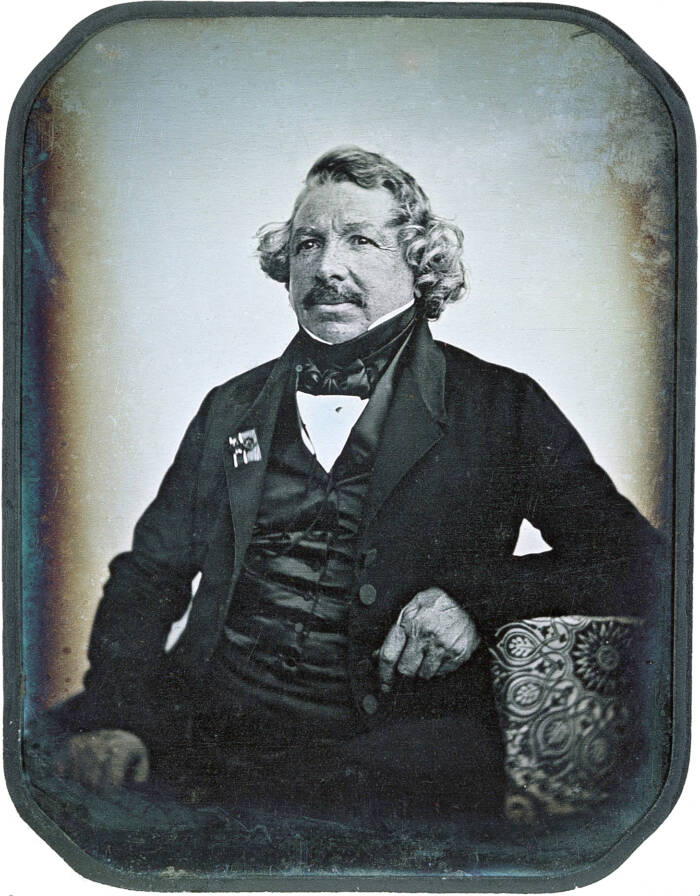

Public DomainA portrait of Louis Daguerre.

Daguerre had wanted to combine Niépce's heliograph with the convenience of the camera obscura, an early version of a projector, and the daguerreotype was the culmination of this work. The process went like this:

First, a copper plate was coated with a layer of silver. This silver was carefully polished until a mirror-like surface was achieved. The clean, polished plate was then sensitized in a box over iodine, forming a light-sensitive layer. Next, the sensitized plate was placed in a camera and exposed to light, with exposure times initially taking up to 15 minutes.

After exposure, the latent image was developed with a dangerous vapor like mercury, which helped render the image visible. This developed image was "fixed," or made permanent, by immersing the plate in a solution of salt. Finally, the finished plate was often sealed under glass for protection.

Though physically fragile, the resulting images were remarkably detailed and clear, and the daguerreotype quickly became popular worldwide, as it was the first publicly available photographic process.

In France, the government acquired the rights to the process and made it "free to the world" in August 1839. In the U.S., the technique was enthusiastically adopted, with numerous studios offering portrait services. By 1850, there were more than 70 daguerreotype studios in New York City alone.

Soon enough, the medium appeared in various places across Europe, Asia, and other regions of the world. But as innovative as the daguerreotype was at the time, its moment would soon fade thanks to further innovations in photography — ones that were more versatile and economical.

The Rise Of Other Photographic Processes

Heritage Image Partnership Ltd/Alamy Stock PhotoA print made from a negative in the 1850s, by Adolphe Braun.

The daguerreotype was extremely popular throughout the 1840s and 1850s, but the eventual introduction of alternative methods proved that the photographic process could be refined even more.

The processes of ambrotypes and tintypes both emerged in the 1850s and offered quicker exposure times than daguerreotypes at a much lower cost, which naturally made them more popular with the general public.

There was also the introduction of the wet collodion process in 1851. Created by Frederick Scott Archer, the process allowed for the creation of glass negatives, enabling multiple positive prints from a single exposure. The wet collodion process reminded some people of the calotype process that had already been introduced by William Henry Fox Talbot about a decade earlier.

But while Talbot's process never quite took off like the daguerreotype, Archer's process highlighted a key limitation of the daguerreotype: its non-reproducibility. Each daguerreotype was a one-of-a-kind image, which meant the process could not be used to mass-produce photos.

This flaw was made even more apparent in 1854, when André-Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri patented the carte-de-visite, a small, inexpensive photograph mounted on a card that was often created by using the collodion process. And while refinements to the daguerreotype process continued to be made, the medium's fate was effectively sealed in 1888 when George Eastman debuted the Kodak, the first successful roll-film hand camera — thanks, in no small part, to Eastman's clever marketing strategies.

Kodak cameras remained dominant well into the mid-20th century and further photographic innovations led us to the modern day, where we can produce stunningly high-resolution images at a moment's notice with a camera that's thinner than a typical paperback book.

Still, it's hard to deny just how much the daguerreotype revolutionized the world of photography and brought the medium to people across the globe.

Next, see our gallery of the world's first color photos. Or, see colorized portraits of the oldest generation ever photographed.