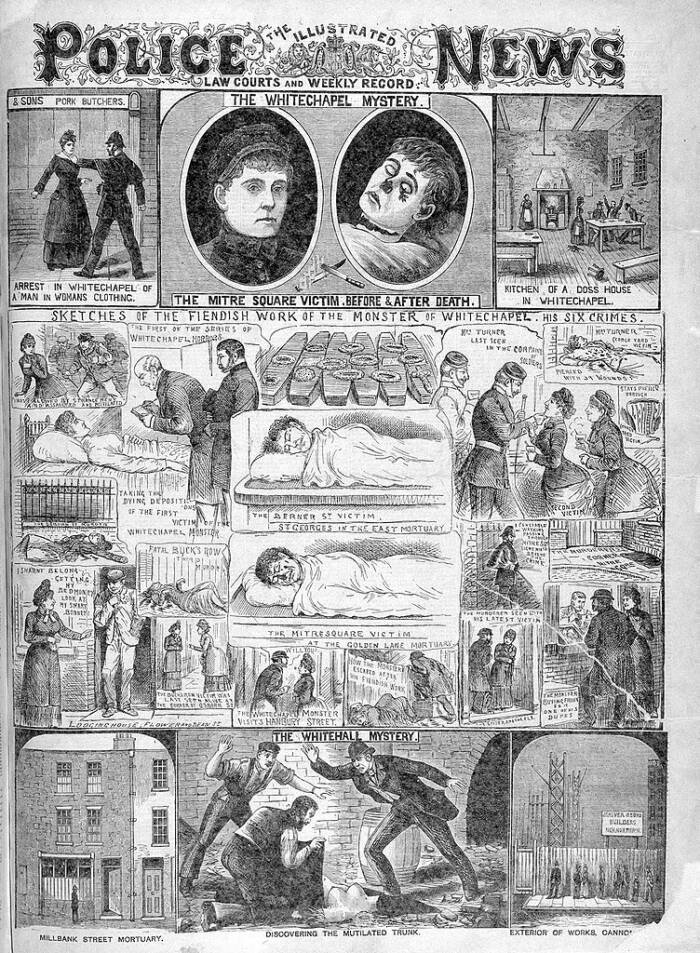

Discover the grisly stories of the five victims of Jack the Ripper who were brutally snuffed out in London's Whitechapel district starting in the summer of 1888.

To this day, no one knows Jack the Ripper’s identity, but millions around the world know his story. Over a span of several bloody weeks in 1888, the shadowy serial killer terrorized the London neighborhood of Whitechapel. Readers then, like readers now, consumed every tantalizing new detail about the killer before he seemingly disappeared that November. He’s still remembered today, but Jack the Ripper’s victims have been largely forgotten.

So who were the five women considered to be the canonical victims of Jack the Ripper?

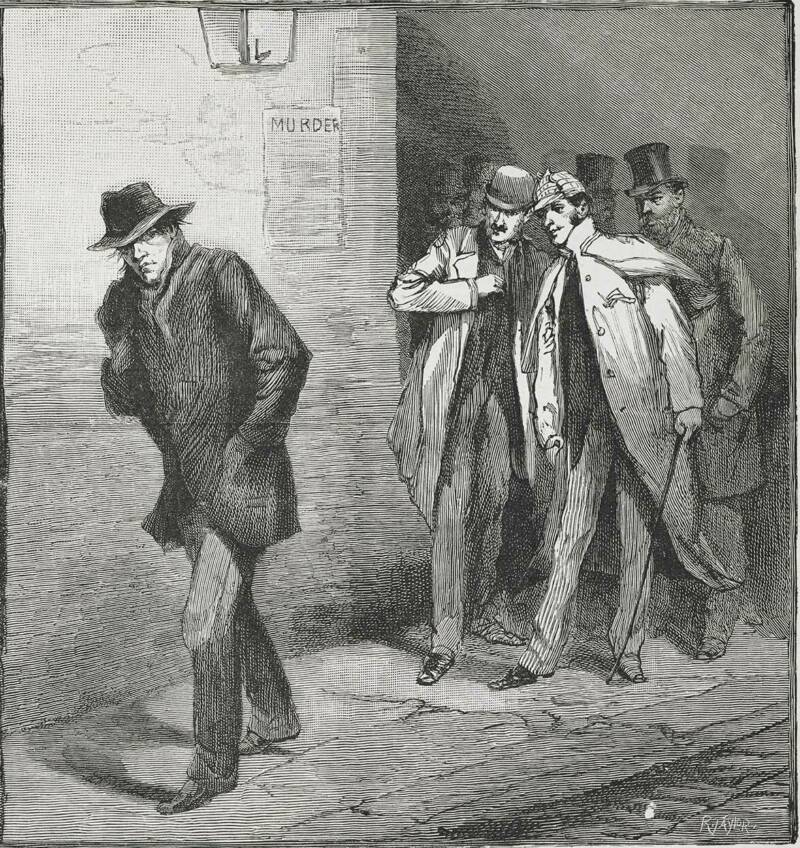

Public DomainJack the Ripper’s victims have largely been overshadowed by the intrigue over the killer’s identity.

Mary Ann Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes, and Mary Jane Kelly all had the misfortune to cross Jack the Ripper’s path in 1888. And though they met the same bloody end, each of the women had followed a different — albeit strikingly similar — path to Whitechapel.

The five women suffered from a myriad of tragedies: they’d gone through divorces, lost loved ones, and spiraled into alcoholism. Most of them had turned to sex work to get by, and spent their days in cheap lodging houses and their nights wandering the streets of Whitechapel.

These are the little-known stories of Jack the Ripper’s victims, the five women brutally killed by the Whitechapel Murderer in 1888.

Jack The Ripper’s First Victim, Mary Ann Nichols

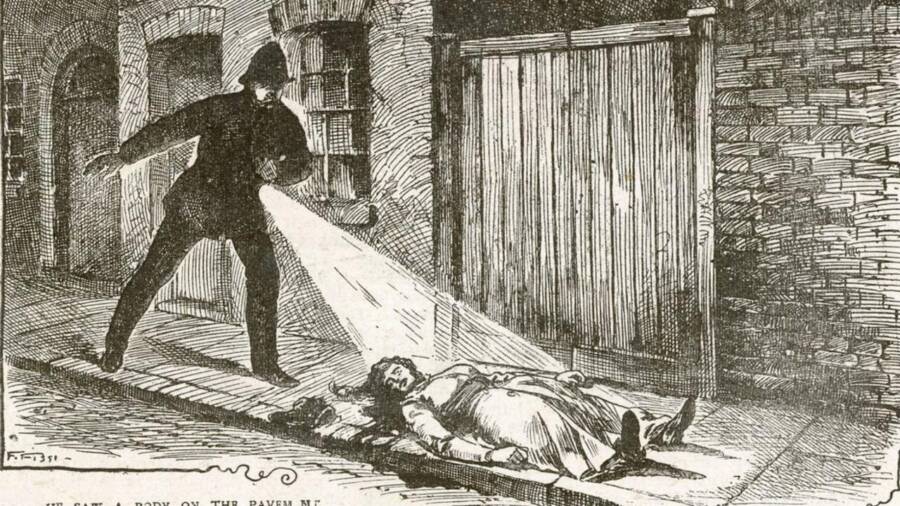

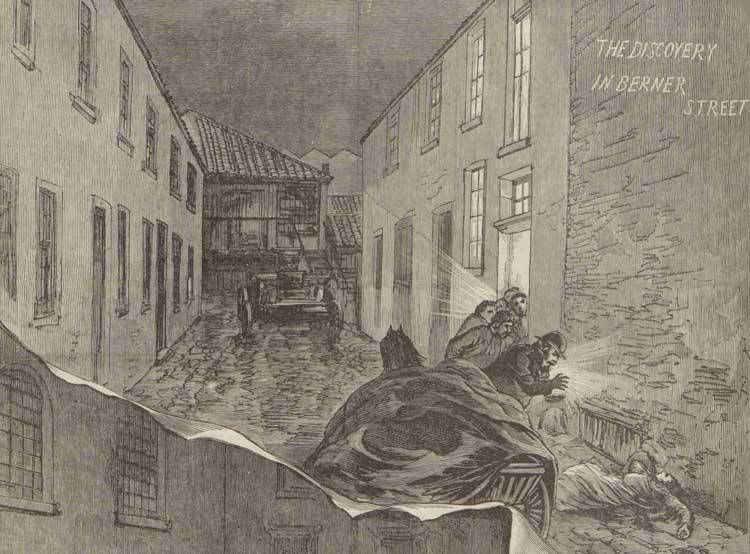

Public DomainThe discovery of Mary Ann Nichols, Jack the Ripper’s first victim, as depicted in 1888.

Jack the Ripper’s first victim, Mary Ann Nichols, led a life marked with hardships. Born in 1845, she married in 1864 and had five children. But her marriage fell apart by 1880. Nicholas claimed her husband had been unfaithful; he claimed that she was an alcoholic.

Regardless of who was at fault, the divorce made Nichols’ life sorely unstable. She bounced from place to place, sometimes staying in lodging houses, sometimes with lovers, and sometimes with her father. She largely relied on an allowance from her ex-husband, but he stopped paying it in 1881, claiming that Nichols was living an “immoral life.”

Nichols tried holding down jobs to make ends meet. But though she got a job as a domestic servant in April 1888, Nichols lasted just three months — then she absconded with three pounds worth of their clothing.

By August 1888, Mary Ann Nichols was scraping by and living in a lodging house. On her last night alive, August 30, she went to a local pub called the Frying Pan Pub and got drunk. She got so drunk that she spent the money she needed for a bed at the lodging house and was turned away at the door.

“Never mind,” she reportedly said. Apparently unconcerned about finding the money for a room, Nichols pointed to her straw bonnet trimmed with black velvet and added: “I’ll soon get my doss money. See what a jolly bonnet I’ve got now.”

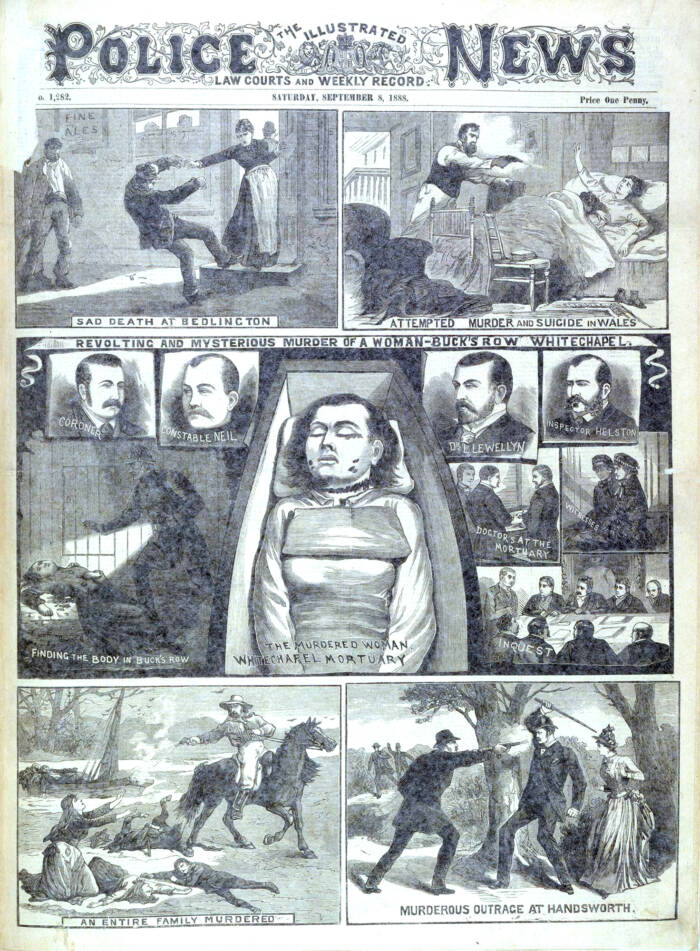

Public DomainMary Ann Nichols’s murder was just the first in a series of grisly killings in Whitechapel starting in the summer of 1888.

She walked off, likely planning to use sex work to earn enough money for a room. At around 2:30 a.m., she ran into Emily Holland, a fellow lodger, who tried to convince Nichols to return to the lodging house. Holland later recalled that Nichols refused to return with her and that she seemed drunk.

“I have had my lodging money three times today,” Nichols told her, “and I have spent it.”

Holland was the last person to ever see Mary Ann Nichols alive. About an hour later, Nichols’ slumped form was discovered on Buck Row. Investigators found that her throat was cut. She’d also been stabbed in the vagina and the abdomen. Her straw hat was lying close nearby.

Mary Ann Nichols was Jack the Ripper’s first victim, but no one knew that yet. Life in Whitechapel could be violent — and brief — and it wasn’t altogether unusual for a sex worker to be killed. But just over a week later, another woman was killed in a similar manner.

Police in Whitechapel began to suspect that there was a killer on the loose.

Annie Chapman

Public DomainAnnie Chapman and her husband, John, before their marriage fell apart.

Like Mary Ann Nichols, Annie Chapman — the second of Jack the Ripper’s victims — led a difficult life. Born in 1840, her father died by suicide when she was a girl and Chapman started drinking at a young age.

She married her husband John in 1869, but their life began to unravel after they had children. Of their three offspring, one was born disabled and later surrendered to an institution, and another died at the age of 12. Chapman and her husband began to drink heavily and separated in the mid-1880s.

Though police found Chapman at fault for the divorce (they blamed her “drunken and immoral ways” for the end of the marriage) John died of cirrhosis of the liver and dropsy shortly after they separated. With his death, Chapman also lost the ten shillings he gave her each week.

And so like Nichols, Chapman started living in lodging houses. Like Nichols, she turned to sex work to get by.

By 1888, she was a regular at Crossingham’s Lodging House on 35 Dorset Street. Her fellow lodgers remembered Annie Chapman as being “inoffensive” and ill, as she possibly suffered from tuberculosis and syphilis. Shortly before her death, however, she got into a fight with a female lodger — possibly over a man and possibly over a bar of soap.

All in all, life wasn’t going that well for Chapmany by September 1888. She was sicker than ever — her fellow lodgers remember seeing her with pills and a bottle of medicine — and complained of being “too ill to do anything.”

Then, in an eerie echo of Mary Ann Nichols’ murder, Chapman was turned away from her lodging house on the morning of Sept. 8, 1888. She didn’t have enough money for a bed, but she promised to be back soon.

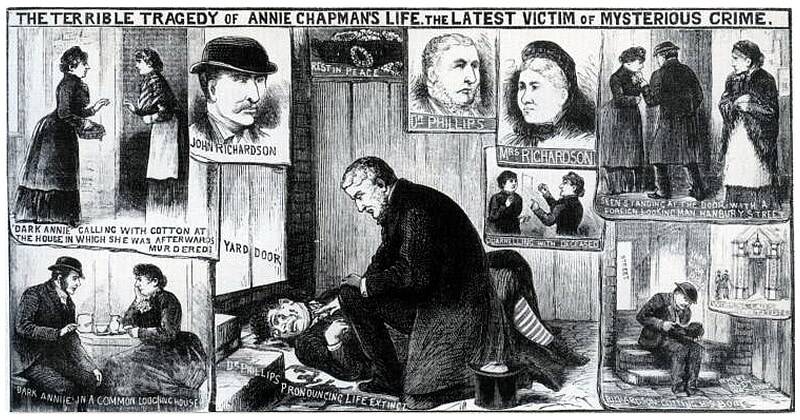

Instead, around 5:30 a.m., Annie Chapman seemed to meet Jack the Ripper. A witness remembered seeing her talking to a man before they disappeared together into the backyard of No. 29 Hanbury Street. About 30 minutes later, a man passing through the backyard found Chapman dead.

Public DomainA depiction of the doctor examining Annie Chapman’s mutilated body.

Jack the Ripper’s second victim had been brutally murdered. Her body was “terribly mutilated,” her throat had been cut, and her abdomen had been “entirely laid open” with “the intestines…lifted out of the body.” What’s more, Chapman’s killer had removed her uterus, the “upper portion of the vagina” and “the posterior two-thirds of the bladder.”

Shortly thereafter, the “Whitechapel Murderer” got a new name. On Sept. 29, Scotland Yard received a letter purportedly from the killer in which he called himself Jack the Ripper for the first time.

Jack The Ripper’s Victims: Elizabeth Stride

Public DomainElizabeth Stride was not as brutally killed as the Jack the Ripper’s victims Nichols and Chapman, leading police to believe he’d been interrupted.

Unlike Jack the Ripper’s victims Mary Ann Nichols and Annie Chapman, his third victim Elizabeth Stride was not born in England but Sweden. Sadly, however, she would meet the same fate.

Born in 1843 as Elisabeth Gustafsdotter, Stride fatefully made her way to England in 1866. Though she married her husband John Thomas Stride in 1869, they had a seemingly volatile relationship, and separated for good in 1881. Stride’s ex-husband died of tuberculosis in 1884, and Stride took to telling people that both he and their imaginary child had died in a shipwreck in the River Thames. She falsely claimed that she had survived the wreck.

Like Nichols and Chapman, Stride used sex work to make ends meet. And like Nichols and Chapman, she became an alcoholic. Stride was arrested on approximately eight occasions for drunk and disorderly conduct, despite an acquaintance remembering her as being a relatively calm person.

By 1888, she was living in a Whitechapel lodging house. Though Nichols and Chapman were both turned away from their lodging houses, however, Stride appeared to have a good amount of funds on her last night alive. On Sept. 29, Stride cleaned two rooms at the lodging house and received sixpence.

Then, she put on nice clothing and went out.

That night, multiple witnesses saw Stride in the company of men (in one case, she was hugging and kissing her companion) but it’s unclear if they were different men or one man. In any case, the night took an alarming turn just after midnight, when a witness named Israel Schwartz saw a man grab Stride and throw her to the ground. Scared for his own life, Schwartz fled.

Public DomainJust 45 minutes after Elizabeth Stride was killed, Jack the Ripper’s fourth victim was found.

Less than an hour later, Stride’s body was found. Her throat had been cut so deeply that she was almost decapitated, but she did not seem to be as mutilated at Jack the Ripper’s other victims.

Investigators soon speculated that whoever killed Stride was interrupted during the murder, which would account for the less brutal crime scene. And, indeed, Jack the Ripper’s fourth victim was found just 45 minutes later.

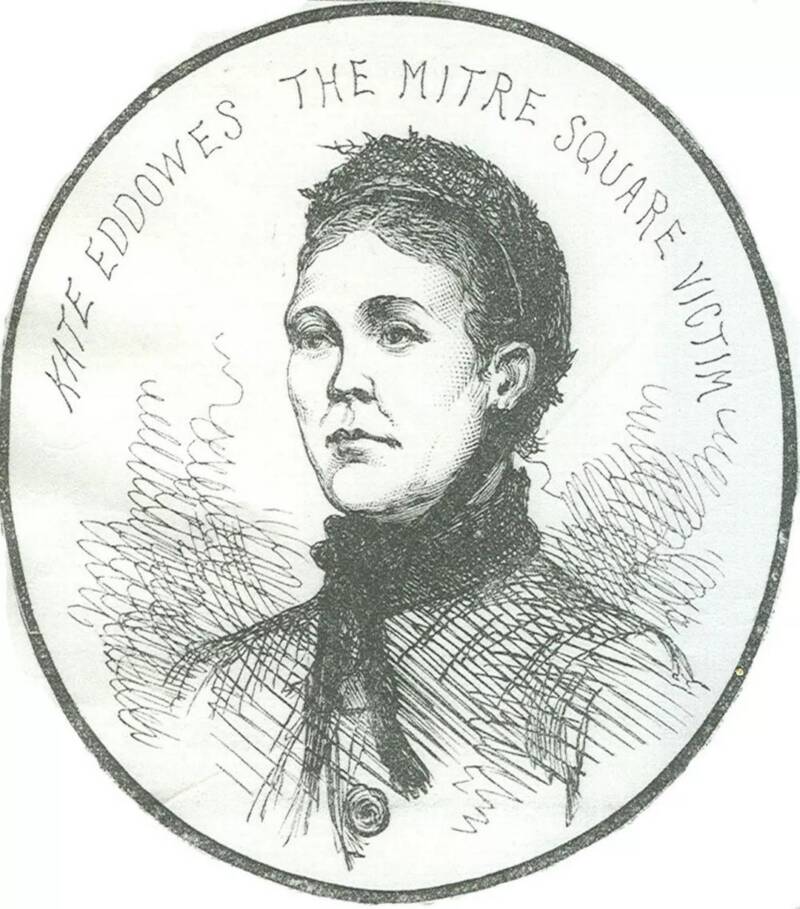

Catherine Eddowes

Public DomainCatherine Eddowes, Jack the Ripper’s fifth canonical victim.

Catherine Eddowes was found murdered on the morning of Sept. 30, 1888, shortly after Elizabeth Stride’s body was found. But the story of her life differs in many ways from Jack the Ripper’s victims.

Born in 1842, Eddowes spent many years of her life with a man named Thomas Conway (she even had TC tattooed on her arm). Though unmarried, they had three children together and made a living selling cheap novels and “gallows ballads.” But the two split in 1888. According to their daughter, Annie it was ” “entirely on account of her drinking habits.”

Whereas some of Jack the Ripper’s victims turned to sex work after losing their husbands, however, Eddowes carried on. Moving into a lodging house, she met a man named John Kelly. Eddowes even took Kelly’s last name, and people who knew her described her as a” very jolly woman, always singing.” They deny that she was a sex worker.

However, Catherine Eddowes was very poor. In her last few days alive, she and Kelly tried to make money by harvesting hops. When this didn’t go well, Kelly went to stay at a lodging house, while Eddowes went to the casual ward, where the poor could go when they were ill.

There, she allegedly had an exchange with a superintendent and claimed that she planned to “earn the reward offered for the apprehension of the Whitechapel murderer,” adding, “I think I know him.”

Whether or not this is true, Eddowes did need money — badly. After she was kicked out of the casual ward for unclear reasons, she told Kelly she would try to get money from her daughter. Instead, it seems that she went and got drunk. Police found her sprawled on the ground on Aldgate Street around 8 p.m., and took her to the Bishopsgate Police Station to sleep it off.

Tragically, police let her go some time after midnight on Sept. 30. Three witnesses saw her speaking to a man around 1:30 a.m., and Eddowes’ dead body was discovered in Mitre Square around 1:45 a.m.

Public DomainOf all Jack the Ripper’s victims, Catherine Eddowes’ murder was among the most brutal.

Of all Jack the Ripper’s so far, Eddowes’ murder was the most brutal. Her throat had been cut, she had been disemboweled, her face was mutilated, and her attacker had removed her left kidney and most of her uterus. Investigators suspected that the killer, interrupted while killing Stride, had taken his murderous rage out on her.

Police also found some clues nearby, including a scrap of apron and graffiti that read: “The Juwes are the men that Will not be Blamed for nothing.” However, they were unsure if it this had anything to do with the case and washed it away in case it caused anti-Semitic riots.

A few weeks later, they got a clue that did seem connected with the case: a letter addressed “From Hell” which contained a piece of human kidney.

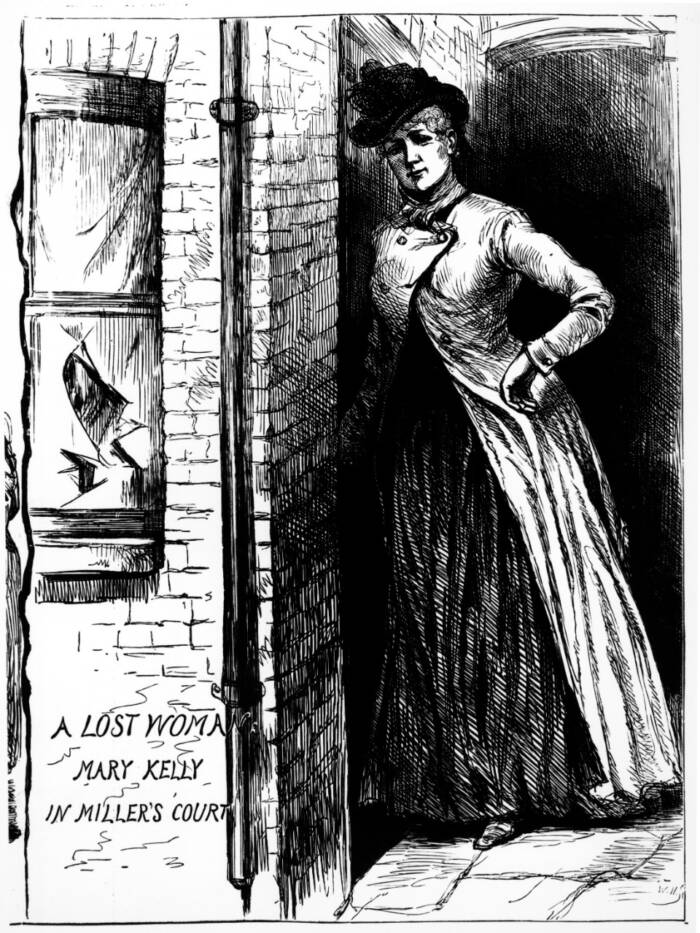

Victims Of Jack The Ripper: Mary Jane Kelly

Public DomainMary Jane Kelly, the last of Jack the Ripper’s victims.

Of all Jack the Ripper’s victims, Mary Jane Kelly — the fifth and last canonical victim — died the most gruesome death.

Little is known for sure about her early life. She was born in 1863 in Ireland, and eventually made her way to Wales. Kelly was briefly married to a coal miner, but turned to sex work after he died in an accident. By 1884, she was living in London and allegedly working at an upscale brothel.

In 1886, she met Joseph Barnett at Cooley’s Lodging House. They had not known each other long — they had purportedly met just twice — when they decided to move in together. The couple was kicked out out of their first home together for getting drunk and not paying their rent, and soon moved into 13 Miller’s Court on Dorset Street.

When Barnett lost his job, Kelly returned to sex work. And though he left 13 Miller’s Court after they had a fight, the couple continued to see each other. In fact, Barnett even saw Kelly on Nov. 8, 1888 — the night before she died.

After staying for an hour, Barnett left her at 8 p.m. Later that night, Kelly went out and multiple witnesses saw her drinking at pubs. She could be heard singing in her room in the early hours of the morning on Nov. 9, but at some point the singing stopped.

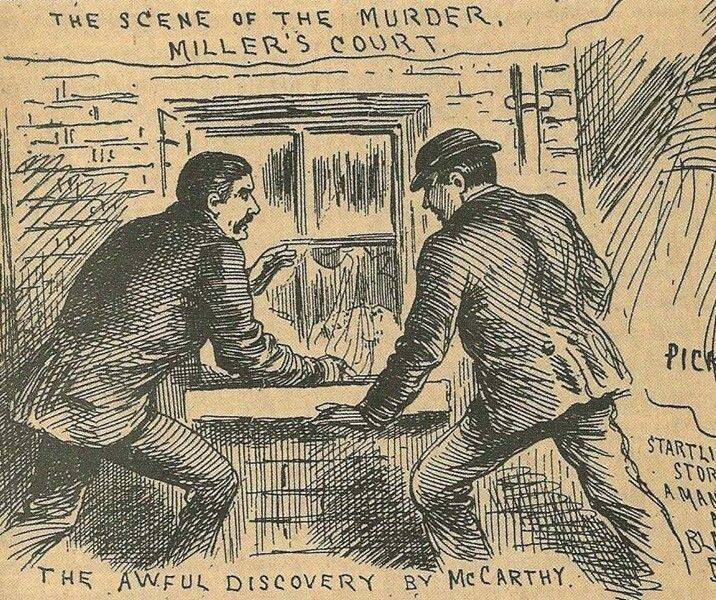

Then, shortly before noon, Kelly’s landlord came to collect rent. When no one answered the door, he looked through the window — and saw her mutilated body.

Police soon arrived on the scene, and found the 25-year-old in bed, with her head turned. Kelly’s killer had carved out her abdominal cavity, cut off parts of her face and breasts, removed part of her left arm, and strewn her organs across the room. Her heart was missing.

Public DomainMary Jane Kelly was the most mutilated of Jack the Ripper’s victims.

To investigators chasing Jack the Ripper, it must have seemed like an alarming escalation. Like Catherine Eddowes, Mary Jane Kelly had been brutally murdered and dismembered. But Kelly was the last of Jack the Ripper’s canonical victims. After that, the killer seemed to disappear.

He stopped killing, but he’s remained an object of fascination for over a century. Theories about Jack the Ripper’s identity have proliferated since the 1880s, and researchers are still working to figure out who he was.

Meanwhile, the stories Jack the Ripper’s victims have been all but forgotten. Though they each came from different places and suffered from different tragedies, they all had the terrible luck to cross his murderous path.

After this look at Jack the Ripper’s victims, meet some of the most compelling Jack the Ripper suspects, including Polish barber Aaron Kosminski.